Daughter of the Dynasties

by Nicoletta Giuseffi

Carlotta leads my hand into the skull’s mouth and the mandible quivers. She holds me fast, the coarse lace glove on her grasping fingers scratches my arm. Her laughing eyes lock onto mine like another set of teeth. There are other people in the surrounding dark, appearing from the shadows and submerging again, uncountable, observing, whispering. I am so close to belonging, to being one of them.

“Swallow her,” she dares.

The jaw snaps around my hand, tearing pink skin and severing tendons, pulling sinews from the spaces between my bones as it drinks without a throat. I shriek into a void of pain as the space behind the pedestal shimmers with fullness and the double-image outline of the crocodile writhes in the bliss of feeding. Everyone cheers. There’s a crunch and I weigh less. Carlotta throws my arm up, as if to raise my vanished hand in victory.

My radius and ulna, severed, ragged, gleam whitely beneath the spotlight.

• • •

When I fall, I wish that I am fainting, but I remain awake for the agony of the mending. Adile stands like a spire behind me, watching the seamstress who made her dresses close me up. Her eyes are lakes of fascination; her breath reeks of champagne. Clutching the flute in her hand, she asks how long it will be before the debutante is ready to reap her rewards.

“Not very long. The blood ruined her clothes. Once we’ve dressed her, she’ll be able to join the others.”

“Who was her clothier? Villeroyale? Milano? Bertin?”

“No label.”

“No label,” Adile hisses, “I knew it. Her father was only a comte after all. Carlotta makes such poor choices.” Merciless Adile. She slapped me once, at a party, and I spilled wine down my frock. Everyone laughed. It was red.

Once the seamstress has stopped the bleeding, she stands me up and a troop of girls with the blushing welts of the lash on their faces replace my clothes in an imprisoning froth of petticoats and whalebone stays. I jump when the pins they use to fasten my jacket and gown prick my flesh at Adile’s direction. Ribbons and lace drown me like a fishwife in a siren’s arms. Adile herself does my makeup, hiding any untried loveliness in the cruel beauty of the secret court and its mercury, its vermillion, its lead.

“You’re a lucky girl,” Adile says, and her lips sizzle the hairs on the nape of my neck. Her gracile fingers ply my collarbones, pale and exposed. “I have known man, but never animal. A lover has beaten me, he was a king’s son, but the Dynasties have never blessed me. The only pain I’ve known is of this world. A lucky girl indeed. Welcome to our society. You’ll stay here with us, counting the nights until the moon is empty. When it’s darkest, the Dynasties walk.”

• • •

We all devour trays of ortolan together in the yellow chamber in the east wing. The wallpaper climbs continually into the bubbling lines of molding at the ceiling. “Do you see it?” I ask, pointing upward to the cornice.

“It’s the ergot,” Carlotta says, the butterfly wing of her fan fluttering against her face. She’s sweating. The air on the island is warm and sticky in the early afternoon, and within its pall hangs the searing mixture of a hundred different phials of perfume. “They feed the ortolan just enough, before they roast it. Don’t eat too many. You’ll turn into a witch.”

I’ve had half a dozen of the birds, fat with millet, held loose around the neck and dropped whole into the mouth. Their organs burst, their bones crunch, and I am reminded of the crocodile jaw, the queasy horror of the pain, and the ecstasy which followed. Around me are women who would not hesitate to eat me the same way, if I were not one of their order now. Some of them are missing fingers. One is missing a foot. A girl with a gray powdered wig and red-ringed eyes is missing an ear. She wears six earrings on the other.

“May I lift my head?” Simon asks, his shoulders shaking. He’s on his knees, speaking into the windowsill where his teeth are clenched.

“You’re too handsome. It’s obnoxious,” Georgina yawns, twirling a finger in a cup of whipped cream. “When you’re here, you’re close to the Dynasties, but you mustn’t make a fuss or spit invectives like your friend. He’s alive, but they’re draining him in the other room. I want Milano to make me a corset from his skin. I want to feel his nipples when they dress me in the morning.”

Simon shudders, but I can see his breeches rise in the front when she pushes on his head with all her might. His teeth scrape curls of gold paint from the sill.

“He obeys, don’t hurt him.” I cannot believe what I’ve said.

“Do you fancy him? He’s like all the others. They have everything except what we have, and they can’t feel it like we do. Are you going to try and teach him?”

“I know the flavor of loss. I can help him,” I reply.

Carlotta stands up, turning, the great brim of her skirt twisting behind her like a rose rearing its swollen head. “We want him. For our flesh,” she says. “You can have his friend when you’re working off the skin.”

Georgina’s mouth twitches like a dog smelling the rippling glissando of grease splashing from a sizzling roast onto the bricks of the oven. She kisses the back of Simon’s head, drooling into his hair, and he scrambles up into our arms, where we pet and coo to him. His skin is tea with milk, his blonde hair the lemon, his lips the sugar. I whisper, telling him he’s a fool to come here. He says the king his father sent him.

• • •

The full moon retches her gorge of silver onto the howling splendor of the first night. Revelers are rolling in the galleries, hanging from the balconies, hunting in the hedge maze. Black smoke churns from bonfires around the gardens and the lakeshore. I take Simon’s hand and Carlotta cups hers onto the cool, blunt porcelain rod covering my truncated arm.

She pulls me into a salon filled with antlers, a hundred forests of fine young bucks put to the rifle. The shadows pierce me through with dizzy uncertainty. I squint, watching discarded handkerchiefs dangling wet with pleasure seekers’ blood upon the antlers become the peeling velvet of the hunted deer. While I stand circling, my neck craned to a trompe l’oeil of hounds and horses, Carlotta stuffs a Queen Anne pistol in my hand. She throws open the doors leading to the grounds and tells Simon to run.

We give chase, and in the excitement, I forget I’ve never held a gun before. Down the marble steps I go, past statues shedding their topmost layer of skin, giggling like mad pierrot under the bootheel of the world. Simon scrambles, trips, jumps over couples rolling in the manicured yard, dives through hedges plumed with jeering roses and somehow evades their thorns. His coattails fly behind him like the wings of a dove, only he cannot soar away. The twisting maze ahead consumes him. I follow, eager to be swallowed, a fly into a lion’s mouth of green and twisting corridors.

Never once do I stop to ask why I am doing this. Never once do I place the gun upon my temple to end the mistake of my coming here, one shot to carry me away to Heaven on a cloud of gunpowder. I am one of them now, I can feel their blood groaning in my ears, their breath rasping through teeth too sharp to touch with my tongue. I pursue Simon’s legs, then his coat, then the traces he leaves behind: a mass of hedge disturbed, a flower bouncing on its stem, a girl with a syringe in her arm and a jeweled eyepatch who shouts, “He’s gone this way!”

Somehow, I’ve lost Carlotta, or else she stopped some distance back to let me take the whole of the pleasure. There are other stalkers and other slain; when I glance into a verdant dead-end courtyard, there is a man lying prone beside Jupiter in marble, his huntress stroking his bloodied hair. Once, I think I’ve caught Simon. I wrap my blunted arm around someone’s neck, but he squeals frailly, and I drop him. Falling to my feet, the stranger pleads for me to protect him. I tell him it’s only the first night. They would never kill anyone on the first night.

My prey waits for me at a fountain, refreshing himself. When he sees me, he does not run, but gives a start and goes paler than any powder can make him.

“Come and sit with me,” he asks, “and take some water. Man cannot live on champagne alone.”

“But woman?” He says nothing.

I fire the pistol into the air and a chorus of celebrating shouts follow the report. My ears are ringing when Simon takes me in his arms and kisses the fruit of my lips. I could have him, now. I could take him, I could kill him, club him to death with the gleaming baton affixed to my elbow, carved with fine designs of feathers and painted with peonies as pretty as those on any teapot. Instead, I put the warm barrel of the pistol in his mouth and let him taste what almost was.

• • •

They talk of the Dynasties each night at supper, led by the girl with the jeweled eyepatch. Carlotta tells me her name is Antonia, and that this island and its manor lie within her family’s ancient right. Sometimes I feel as though the fat ruby cabochon upon her patch is looking at me with suspicion. Across the grand table I hear voices talking of the species of those bone-jaws: the hyena, the polar bear, the wolf, the crocodile. It is difficult to eat with one hand. I place down my fork of veal galantine to lift a goblet of wine and wish I could simply use my lips and teeth to empty my plate. The heat of so many dishes and candles and bodies and of the great hellmouth hearth which disgorged all these she-demons is almost too much to bear.

Someone gestures at me from near where Antonia sits picking apart the head of a suckling pig, and I leave my chair to meet them.

“The Princesse du Sang would like to see you,” says the one-eared girl.

“She’s here, the debutante?” Antonia trills. “Good girl. Let me have a closer look at you.” She does not rise from her seat as she turns my arm to examine the edge of the wound beneath the porcelain. Her gown is the color of the blue veins threading the thin flesh of her neck. When she’s finished, she reaches up and pulls me down by my chin. There are bones pinned in her black wig. “The Dynasties ate your hand. They rarely take so much, but you’re not like us, are you? Not yet. No instinct. A terrified creature, a white doe, not a wolf. Your maidenhead stinks through your skirts. It disturbs my supper.”

My cheeks glow from the pressure of her fingers when she releases me. Carlotta comes around to take my arm and bows low—I curtsey when she pinches me. After that, she pulls me to the stairs, but I make the mistake of Orpheus and look back. Antonia’s jeweled eye is more alive than ever, spearing me through my head with a shaft of red knowing. She is disgusted with my shameful mercy.

The stairs carry us out of the hellish heat of the dining hall and into a bedchamber whose open windows drink the cool air of the silent lake beyond. It is dark, but I hear Simon breathing, I hear chains rattle, and when my eyes fatten on waning moonlight, I see him sitting beside the bed. His jacket is folded on his lap, and he is bound in irons. His cravat is as crisp and white as the serviettes downstairs. There is a clamp of some kind in his hands, and his fingers dance over the metal.

“Good evening,” Simon whispers, and Carlotta slaps him. The amber scent of her perfume is no longer kind—it is miasma and it wishes to harm, to conquer.

Carlotta and I sink into the bedclothes as deep as any diver in the lake. Shifting this way and that, we sigh against our corsets and lift our petticoats to one another, first her, then me. I am too shy to start.

Her teeth sparkle in the moonlight as she bites my earlobe. The first of her fingers feel my blushing privacies. There is a newness to her touch, a horrid newness, a spirit which takes me about the neck and shakes me, screaming, “Why have you wasted so much time without these sweet palpations?” I tell the spirit that I never had the opportunity before.

“They’ll kill you on the last day, if you’re still so new. I shall save your life.”

“You shall give me life,” I gasp, febrile and urgent, as my cosmetics smear against the canvas of her breasts. Simon whimpers and moans, an echo of me, but he is indulging in well-trod sensations, his pain and his pleasure. His right hand tightens a thumbscrew around his left, breaking his nails like bloody eggshells, and when Carlotta presses me to my peak, I hear the crack of tender little finger bones and Simon screams.

• • •

We have kugelhopf in the morning, speckled with dry cherries which look to me like chunks of meat from last night’s feast. My shoulders ache, my thighs are sore, and it is Adile who relieves me from my bed all smiling and telling me a bath awaits me. There is a beast in the adjoining room, a creature of mottled marble perched on golden legs each baring the claws of a different animal. In its mouth it gargles a broth of hot milk and rose petals. I descend inside, helped by the young attendants in white from that first night, their gazes deadened now irretrievably; there is no necromancy for innocence.

While I rest inside that tranquil orifice, the prelapsarian memory of last night sings in lyrics I dare not repeat. I am inside Carlotta’s slumbrous eyes and my nostrils twitch against the recall of her perfume and sweat all mingling with Simon’s shouts as he dooms himself to his exquisite dissipation. After that, I begin dreaming of the final day and of the darkness promising to conceal our dread affairs like yesterday’s lovers, buried early and without a bell to ring for resurrection.

In a dulcet delusion I see the crocodile I could not observe before, who ate my hand and likely wanted more. Beneath the milk steam it smothers me in scabrous scales and bares its underbelly, white as talc, as teeth, for me to press one hand and feel the remnants of my other within, reaching, trying in vain to close on mine. The golden dragon stare of its wise and ancient eyes seems to see me in ways the others don’t. There is no pity in them, no disgust. There is a wordless something passing now between us, and only when I leave the bath and dry with cotton towels do I realize it was dignity, no; majesty.

Adile is waiting, playing chess on a board with only queens against a girl with only one breast in her bodice. She sees me right when she loses and, with a twist of her crimson mouth, grabs my porcelain arm and leads me down the halls past rooms filled with silent sleepers, unfit for daytime revelry after such a productive night. We come at last to a room in the tower, a huge circle of a room clouded with the ashen redolence of fire. A vast array of porcelain limbs lines the walls, enough to build a dozen people with better fortunes than mine. There are hands, grasping hands much more sophisticated than my clumsy rod, and white, unpainted heads which stare with empty eyes. Even without color, I can see the shape of Simon’s face reflected in one of these blanks.

“I fired them yesterday. You’ve been as patient as a girl of your means and station is expected to be, and since we are alone in my workshop, I must tell you: It is a trait I could grow to admire. Other girls with richer blood than yours flail about like fools and break their beautiful limbs, but your placeholder is as shining fresh as when I first made it.”

“I can make it to the end. I have instinct now.”

“Of course you do.”

The artisan lays me out upon the swollen pink tongue of chaise lounge, smiling but superior in her eyes. My limb is removed and the bare, bloody stump remains. Adile winds away the bandages and produces a hand not unlike the one I lost: powder-white porcelain flesh, a painted set of nails. There are shafts of gold sharp as stiletto knives protruding from its wrist. Without a word of preparation, the lady artificer thrusts this miraculous double atop my wound, lancing the shafts deep into the muscle.

That I vomit from the pain seems to satisfy her.

• • •

Around night thirteen, a rumor circulates that I can play the harpsichord, and they will not hear a word of protest until I’ve settled the matter. Ravening with excitement, they herd me into the music chamber where an ophidian Melusine graces a cartouche above the door. Some of the men are playing a serenade on violin, but like four cut throats, a sharp, discordant note ends their string quartet the moment they see the first arriving hint of satin skirt. The women all take their places on chair and settee while the men stand, their hands folded behind their flaring justaucorps but for one, Simon. He is wearing gloves.

The harpsichord is carved in walnut, finished in gold and tortoiseshell. As I stand before it, the open lid reveals its thriving organs, strings and bridges the veins and bones of another crouching monster in this den of wild things.

“She’s not meant to be here.”

“What ugly clutch of notes do you think she’ll play?”

“The final night devours weak girls of thin blood. She won’t survive.”

My legs quiver as I take position at the keyboard, my old hand ready, waiting, my new hand quivering with the indecision of every untaken action. I test the keys with my new fingers and find they move as easily as they had before and so, with no sheet upon the music rack, I attack the song without mercy. I must show them I am not a wilting rose and that my thorns are sharp.

The room becomes a shrine to a whirling Scarlatti sonata, violent arpeggios rampaging up the walls and out the windows, crawling and hanging upon everything. My body rocks and heaves into the keyboards, barely able to contain the force of the music. A grapeshot hail of prestissimo notes puncture the gathered nobles who have never heard their court musicians play so well. They are wounded, bruised and bloody on the inside where their hearts burn like autumn leaves in fires of outrage that such perfection could be hiding in some nothing girl, a comte’s daughter, or lower, goes another rumor.

There are so many notes that when I miss an F with my real hand, they do not notice, their ears are not so keen as mine, but once upon a time I felt the switch’s sting for such a maladroit mistake.

• • •

As the nights progress, the sky devours the moon, bite by bite, until a shy sliver is all that’s left. In such enervated light, the fairest pastel sitting room becomes a debtor’s prison of bilious hues, and the multi-colored macaron piled tier on tier resemble mussels fished up from the lake, seeping with algae.

Simon paces in front of an empty fireplace, stopping now and then to examine the painted screen and its dismembered peacocks. A bestial fervor wells up inside me as I watch him from my seat, and I can scarcely resist the urge to pounce upon him and hold him to the ground, to eat his throat, to kiss him, to make him marry me and take me far from the island’s endless Bacchanalia. Instead, I look over my shoulder for another face and, finding none, take comfort in our solitude.

“It’s not too late to leave. They say terrible things happen on the final night. Terrible, glorious things. We can leave, can’t we? Together?” I am the victim of a frenzied ambivalence.

The man looks boyish in his fear. His lip is twitching, about to twist and turn the valves of his tear ducts. Then, all at once, a remarkable transformation: he looks at me as he fondles the fob of his watch, and he seems for a moment the lord he was born to be, poised and august, wise, prudent. Then he laughs, or sobs, I cannot tell these days, and gestures to the open window. Some of the ladies are practicing their howls in the gardens.

“You don’t know? Were you so dazzled by the delights of your tenancy here that you did not smell the burning wood that first night?”

“Mind your tone with me. You are secondary here, and your masochistic rituals leave little of your own pleasure obscured.” My hostility shocks me.

“You grow sharper, but even with their power you’re as foolish as a milkmaid. Discard the fantasy of escaping,” Simon drawls, leaning against the carved fish of the mantelpiece. “They burned the boats after we arrived. All of them. No one will leave this island until their people send another. We men, who drifted here on currents of lubricious fables, are going to die. Isn’t it wonderful? To end a life of iniquity without jeopardizing your immortal soul. Speed me to God’s blissful Heaven, my dear, I beg of you.”

He is temptation, the incubus of a thousand sublimated desires, holding in his every supple inch a bloody red escape from the confines of my tender human shell. Gripped by the reverie of shredding his limbs into ragged strips, a guttural hiss bulges up my throat, pours from my lips, bounces off the walls. Simon shudders and takes a step forward, holding out his damaged hands, urging me to end the masquerade and show him what I am.

If he knew I was a failed composer’s daughter, a pauper, he’d laugh, then turn me over to the others. I can see them now, all gathered in a circle, asking, what is she? and, is she one of us, or one of them?

I will show them the only blood of value is that which spills.

• • •

The final night is darker than I could have imagined. Everyone has slept away the day in anticipation of the disappearing moon, her act at last ended, her curtain drawn. Now we become the players, slipping from our beds and calling in our handmaids to costume us, bending down for our wigs and ribbons.

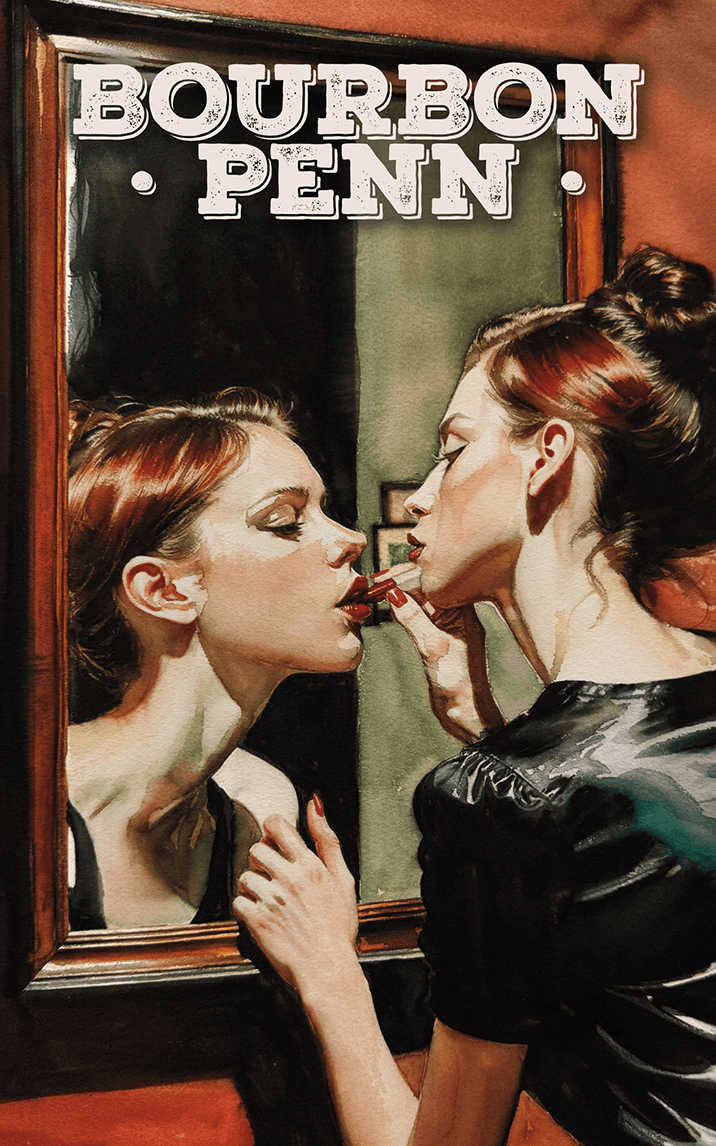

Fingers as light and deft as plover beaks prepare my face for a second debut. “The mirror, mademoiselle,” the handmaids urge, and I turn to admire my integument of emerald scutes, my ever-smiling mouth. Without ears for earrings the jewels must line my sagging neck and smother my striated décolletage. There at my scaled elbow grows the porcelain prosthesis, but it too has changed with the rising of the empty moon, becoming squat, clawed, and fit for scrabbling through the sand. Instead, I hold a fan within its lustrous grip—the air is undulating with the heat of hungry expectation.

Before I take my leave, I tell them to lock the door. They are human and helpless, and it would be a shame for their infirmities to spell their end.

Instead of the glut of laughter and secret conversation from every corridor, I hear the rustling of chase, assault, predation. Navigating the galleries reveals an open door and a man inside who does not seem as resigned as dear Simon. A woman with the jaws of a hyena and a paw of porcelain upon her leg has splayed him across an escritoire. She’s taken his arm in her mouth, and with molars meant for crushing bone she does just that, then drinks the honey of marrow with the tisane of blood. His sinews separate like the cut threads of lives, his fluids baste her in shots, her fur prickles into sopping peaks.

As I descend the stairs, a man crawls up to meet me, but one of the girls has him by the ankle and her great snout severs the tendon with a loud snap. He turns on her, a scavenged pistol in his hand, and fires into her vast whiteness. To a bear of such ferocious size, it is but a glancing blow, a thrilling stimulant, an affront which demands redress. She heaves her bulk atop him, her dress splits down the back, and with kiln-fired claws she slaps the skin from his face. Only a gray, grinning visage remains.

There are diners in the banquet hall, a pack of ladies whose black noses twitch against the prescience of a living feast. They have cornered some of the men, who cower, pray, or, like Simon, open their arms to the end. The first to move, a silver she-wolf in an ochrous robe à l’anglaise, twitches her pearly false ear and leaps onto a young man with close-cropped hair. At this signal, the scene becomes a rocaille of orgiastic carnage, and blood leaps from its epicenter onto the walls and floor like so much wet paint.

I cannot be compelled to join the other girls in their pursuits; I have my own. His scent is oily with perspiration, and the particles of fear tinge it like the flavors hidden in good wine. I heave myself down the marble steps, past statues of muscle and bone. As the manor’s joyous golden glow fades behind me, so the darkness of the gardens grows before, but nothing can obscure what is mine from my questing senses. I’ve chased him once before and I know just where to go. My eyes are sharper now, and the fringes of the hedges sparkle. I follow where his traces travel, bursting through the walls of greenery until at last I see him at the fountain, a languid hand appraising the water, a monster at his side.

The baleful crimson ruby of her eye reproaches me from within her squinted socket. “The Dynasties cannot abide a girl so gentle,” she says, and when she speaks her yellowed fangs grind against each other. She steps sinuously over a heap of skirts and skin, a human Carlotta without a throat, and gestures back to Simon. “Take him. Take him now and let his throne be occupied by Adile’s creations.”

I have seen a lioness once before, in the king’s menagerie. The beast escaped.

Simon recognizes me at once despite my squamous aspect. We both of us shall have our dearest desire, and there is nothing left to say to one another. He beckons me toward the fountain where we kissed that first night, and I slide into the water. While the princess watches, he lays his head upon the stone surround, and I stretch the length of my impressive maw around his crown. I drag him down into the water, my skirts flow out behind me, my tail whips, and I begin to roll. Together we submerge, but only one of us drowns. Once I feel his body cease to struggle, I stand in sopping silks, a water lily risen from her rest, and clench my teeth to loudly burst the pulpy melon of his skull.

A chorus of celebrating howls, roars, and screeches follows the sound.

Copyright © 2025 by Nicoletta Giuseffi