Building 49

by S.F. Wright

My lease was up, I’d grown tired of my neighbors. I found an old yet well-kept building with a one-bedroom available. The rent was high, but I’d gotten a raise during the last year; and if the pictures were representative of what the place actually looked like, it was a beautiful apartment.

On the website, I entered my information and the unit I was interested in; twenty seconds later, my phone rang.

“Mr. Omouingo?”

“Yes?” I was pleasantly surprised that the man had pronounced my name correctly: Oh-mo-oon-go.

“My name’s Craig Fletcher. I’m the leasing manager at 49 Richman Street? I see that you’re interested in apartment 416.”

“Yes.” I added, lightly, “You’re certainly fast.”

“Sorry?”

“I mean”—I laughed— “I just filled out the form on your website 30 seconds ago, and already you’re calling me back.” I expected an artificial chuckle; a modest chortle.

But I was met with silence.

“Hello?”

“Yes?”

“I am,” I said.

“You are what, sir?”

I felt a twinge of annoyance; I wondered if Craig Fletcher was having fun at my expense. But keeping my voice level, I said, “I’m interested in 416.”

“Oh.” Craig Fletcher exhaled heavily, as though he’d just experienced orgasmic relief. “That’s … wonderful, Mr. Omouingo.”

I waited for Craig Fletcher to go on; but again, he was silent, and once more, irritation colored my mood.

“So”—I wondered if Craig Fletcher was alone in his office, or if someone watched him and even listened to this call— “should I—”

“Would you like to come and see it today? I’m here until six.”

“Sure,” I said, coolly, feeling, despite myself, like a youth tolerating an unwanted solicitation of friendship. “What time?”

“Um …” Craig Fletcher faltered. “Any time before six.”

“Fine,” I said. “How about four?”

“Four …” Again, Craig Fletcher dithered. “Four is … perfect, Mr. Omouingo.”

“All right,” I said. “I’ll see you then.”

“Four o’ clock,” Craig Fletcher said. “I’ll be expecting you!”

• • •

The building was on a side street lined with trees. I’d never been on this street before; in fact, I wasn’t even aware that it existed. Most of the block was composed of old, stately apartment buildings with similar architecture and facades. Number 49 stood in the middle of them. I parked; the only sound was the faint echo of my car door’s shutting. No other people were around. Gray clouds drifted over an overcast sky, although the forecast had said that it was to be sunny.

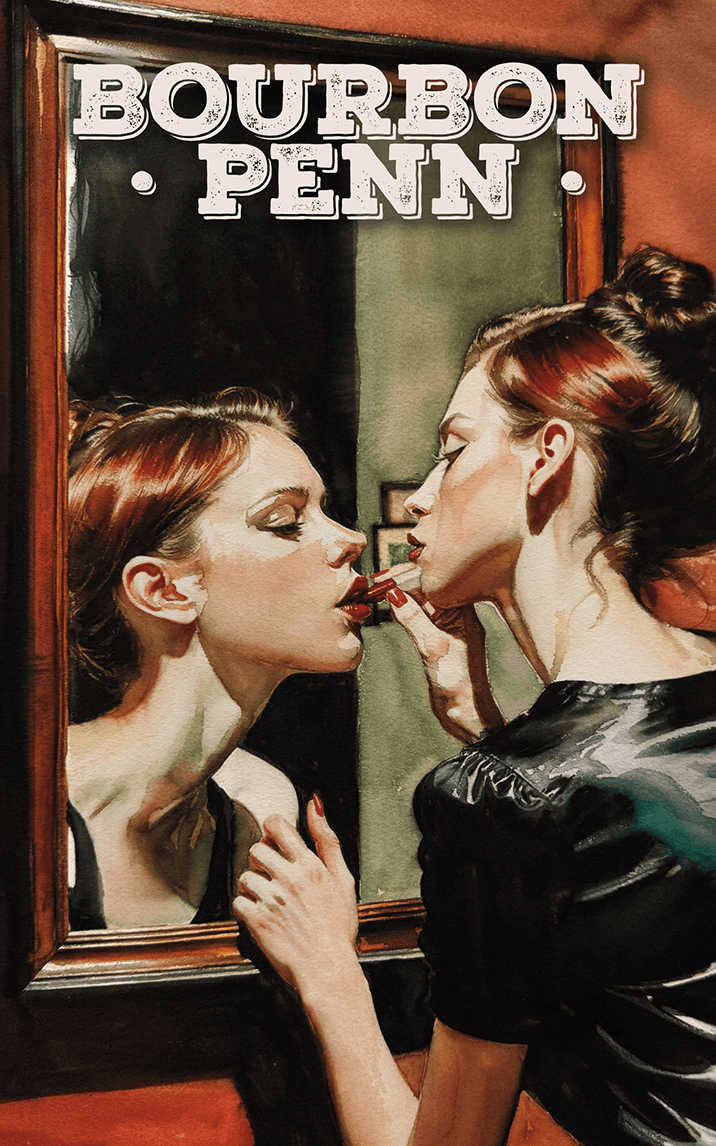

I walked toward the entrance; as I stepped in front of the automatic door, a woman in a purple track suit was leaving. She was in her 30s and had a nice figure, which was accentuated by her outfit. Her face—olive complexion, pert nose, green eyes—wasn’t aesthetically unattractive, yet there was something artificial that negated what otherwise would’ve been beauty or even sex appeal: a mannequin-like aspect, created if not exacerbated by too much makeup. Indeed, her countenance recalled the crude painting of a woman’s visage rather than a face itself. As I passed her—and she smiled at me—I was hit by her perfume, a combination of jasmine and sandalwood; not unpleasant but powerful. Indeed, after the woman left and I pressed the button under the word “management,” the perfume’s aroma lingered, I felt like I’d sneeze.

A large man appeared; he pressed the button to open the second door. The man had thinning hair, a reddish face; he wore a burgundy shirt that might’ve added to his face’s rubicundity, and which was tucked into chinos. He reminded me of the type of giant whom in high school coaches would implore to play football only to discover, despite the Brobdingnagian’s size, that he lacked any athleticism or even coordination. The man needed a shave, though it was possible that the scruffy look was intentional and that he considered it a rustic fashion move.

“Mr. Omouingo?” The man and I shook (his hand surprisingly cold; I expected it to be clammy, if not sweaty). “Craig Fletcher. We spoke on the phone?”

“Right.”

Craig Fletcher studied me; a smile then formed on his face, as though I were a call girl whom he was skeptical would be as attractive as her photos, and now, upon seeing her in person, was quite pleased.

“Come in,” he said, moving, elaborately so, out of the way so that I could enter, as though, even though he was large, he was more than twice that size.

The lobby’s walls and ceiling were white; the granite floors off-white. In the center, on a white rug and near windows that overlooked the street, were two black leather sofas and two black leather chairs. A faint smell of pine air freshener suffused the air, albeit it mixed slightly with the fragrance of sandalwood and jasmine.

“So glad you could make it,” Craig Fletcher said. “Let me show you the apartment.”

• • •

Like the lobby, the walls and ceiling of the fourth floor were white and the floor off-white. The apartment doors were black; their numbers, above the peephole, were in gold. The doors had no odd numbers: e.g., there was 410, 412, 414—but no 409, 411, or 413.

I asked Craig Fletcher about it.

“Well”—we stopped at 416 as he fumbled for the key— “the designer, who was also the building’s original owner, he …” Craig Fletcher put the key into the keyhole. “… had some theories.” He looked at me as if he hoped that I’d infer what he meant, so that he wouldn’t have to expound further.

But puzzled, if not intrigued, I said, “Theories?”

Craig Fletcher nodded, his expression almost pained; he opened the door and, as though grateful for the chance to change the topic, said, “Here it is, Mr. Omouingo.”

The apartment, devoid of furniture albeit replete with appliances—e.g., a refrigerator, oven, stove, microwave, washer and dryer—was spacious; large windows overlooked the street, allowing in much light—or would’ve allowed in much light had it been sunny. But upon walking to the window, I saw that it wasn’t only still overcast, but dark—that crepuscular darkness that can appear in the middle of the day before a storm. And again, I recalled the forecast.

Despite the weather, I imagined what the place would look like with sun flowing in through its windows: splendid, if not glorious.

As I walked around the apartment, which smelled of fresh paint, Craig Fletcher followed me at a distance, while intermittently providing useless commentary: “These floors are really solid”; “You can put a whole sound system over there, if you like”; “The walls have just been painted, which I’m sure you can tell.”

At the door, after having meandered around the apartment a couple of times, while Craig Fletcher clasped his hands, I said, “I’ll take it.”

Craig Fletcher looked at me as though I’d just spoken in another language, or as if he couldn’t believe what he’d just heard.

“I’ll take it,” I repeated, having to swallow rising annoyance.

“You’ll take it?” he said, his tone breathlessly meek—all the more incongruously exasperating coming from a man of his size.

“Yes.”

Fletcher nodded—timidly, and then heartily, as if having convinced himself that what he’d heard me say was real. “You’ve made a great decision.”

I felt pleased, despite myself and the fact that these words came from this man—even proud.

“I’ll email you the forms and contracts,” Fletcher said. “You can read and sign everything online.”

“All right.” I wasn’t only happy about taking the apartment, but relieved that I’d soon be rid of Fletcher’s presence. He stood by the refrigerator, even as I walked toward the door and opened it. He stared at me so appreciatively, it looked as though he were about to break into tears of happiness.

• • •

I was to move into my new place in a few days. However, because it was late in the month, I had difficulty obtaining movers. I tried numerous companies; they all said that they were booked; the quickest they could set up an appointment was in a couple of weeks.

Not knowing what else to do, I called Craig Fletcher, with the vague hope that he might know of some movers who’d be available. I wasn’t sure if this was common practice for new tenants, but I figured that the worst that could happen was that Fletcher would tell me that he didn’t know anybody.

But Fletcher did know of a company. I found their number on the internet, albeit they didn’t have a webpage. Another questionable sign was the manner of the man who answered the phone:

“Hello.” His tone was flat, cold.

“Is this Lucien Movers?”

“Yes.” The man sounded annoyed.

“Hi,” I said. “I know this is last minute, but I’m moving in two days and haven’t been able to get any movers, so—”

“Where you move to?”

“Here in town.” I felt distant hope. “I’m on 20th and—”

“What building?” An edge of impatience colored the man’s voice.

“The building I’m in now? It’s on—”

“The building you move to.” The man sounded almost angry. “Where is building?”

I reminded myself that this company was my last hope. “On Richman Street. It’s—”

“49 Richman Street?” His tone became softer.

“Yes.”

For a few moments, the man didn’t answer.

“Hello? Are—”

“You say in two days?”

“Yes.” I then said, “And I apologize for this being so last minute, but—”

“Saturday we do move. Give me address where you live now.”

Despite Fletcher’s insistence that Lucien Movers was reliable, I was wary about their showing up. But then Saturday afternoon, as I got my mail, I saw the truck approach. It was gray, with no name on its side, and looked as though it hadn’t been cleaned in years; the license plates were so covered in mud that not only was the number concealed, but the state. A man got out; two others stayed in the truck. The man was balding and paunchy; he had pallid skin and gray eyes.

“You are moving?” he said; I recognized his voice from the phone.

“Yes.” I extended my hand. “John Omouingo.”

The man looked at my hand; I didn’t think that he wasn’t going to shake, but then, as though decorum got the better of him, he did—weakly, disinterestedly. His hand was icy.

“You are packed?” He glanced around the neighborhood with what could’ve been dislike, suspicion, or disapproval.

“Yes.” My hand still felt cold from his touch. “All my—”

The man yelled something in a foreign language, the men in the truck got out. They were younger and slimmer than the first man; otherwise, their features were similar.

“Where is apartment?” the first man said; and from that point, neither he nor the other men said another word to me; they quickly and efficiently carried my furniture and boxes, speaking in their language to each other.

When everything was loaded (I’d spent most of this process standing around and occasionally offering ignored advice, such as about a box’s heaviness), I drove to 49 Richman Street; the truck arrived a few minutes later. The sky was a deep azure, which wasn’t unusual—except that when I’d gotten into my car by my former building, the sky had been a light blue mottled with clouds.

At the side entrance, as the head mover put stoppers in the door while the other two opened the back of the truck, I said, “It’s 416, on the fourth floor. If you—”

“I know where apartment is.” The man shouted something in his language, the other two started to unload the truck.

As the movers carried in my furniture and boxes, I stood in the kitchen area. I’d make suggestions, now more assertively, as they involved the placement of furniture; and though none of the movers responded, they followed my directions. Moving my stuff in took an hour; I didn’t see nor hear another tenant: not even a neighbor stopping by to introduce himself, which, had this been a weekday, wouldn’t have been odd, but on a Saturday, I thought a tad strange.

When the head mover gave me my receipt (I’d made the check out to “JK Associates,” which was the same company I was to send my rent to, although the head mover had been so unsociable that I didn’t ask about this), I handed him a ten-dollar bill, and then a ten-dollar bill to each of the other men.

The older man regarded the bill as though it were a balloon or a soiled piece of paper; then, perhaps following the lead of his underlings (who smiled appreciatively upon taking the bills), he folded the bill, in the manner of one indulging an imbecile who’d already exhausted his patience, and put it into his pocket. I thanked him and the other men; the former two smiling wordlessly, the old man saying nothing. Then the latter walked out, and the other two followed.

And I was alone in my new apartment.

• • •

Much about my new place I liked: the washer and dryer and other appliances; the large windows. I also appreciated the apartment’s size, and that the building was kept up and clean. But there were aspects about my new building, and street, that puzzled me. One day, I’d driven home through a late afternoon sunshine, only to turn onto Richman Street with it veiled under a sky full of gray clouds. I made a U-turn and drove back. As soon as I left Richman Street, the sky became clear blue again. I felt excitement and fear traverse through me. I turned around and returned to my building. Now, the sky wasn’t cloudy, but it was still different, darker. I didn’t know what to make of it. Parking my car, I told myself that I was overthinking things; that the weather could simply be erratic.

Another odd thing was that I hardly saw any other residents. Granted, two or three times I ran into the woman I saw when I first came to look at the apartment—and always in the vestibule. Each time, she wore the same (or a similar) track suit and exuded that not unpleasant but strong aroma of jasmine and sandalwood. She’d smile, say hello, and be on her way; no other conversation took place. I didn’t know what floor she lived on, or what her name was.

On another evening, I was taking my garbage to the trash room when, as I reached the corridor’s end, I heard a door open. I turned; in the doorway of apartment 414, a man with white hair stared at me, before he shut the door. I was startled; this was the first person I’d seen in the building apart from the woman in the track suit and Craig Fletcher. However, having lived in cities my whole life, I told myself that this unneighborly behavior wasn’t wholly unexpected.

After I disposed of my garbage and returned to the corridor, I again saw the man standing in his doorway, the door now only slightly ajar; the man again regarded me with amazement or fear. Sensing an opportunity about to disappear, I said, “Hi, I’m John. I just moved into—”

The door shut; I heard the man secure the chain lock.

On another occasion, upon entering my building, I saw Craig Fletcher waiting for the elevator. I hurried to get on with him, so that I wouldn’t have to wait for the other one.

“How’s everything?” he said, politely yet perfunctorily.

I saw this as a chance to get some information; and as we went up (Fletcher was going to the sixth floor), I said, “Can I ask you something?”

Fletcher looked at me with forced friendliness and badly disguised dismay.

“The woman who always wears tracksuits. The slim one. You know who I mean?”

Fletcher appeared even more unsettled; but somehow, he remained stone-faced. “Yes,” he said rather tonelessly, as though he’d been considering telling me that he didn’t know whom I was talking about before realizing that he couldn’t.

The elevator door opened, I held it. “Do you know what her name is?”

Fletcher again looked conflicted; he seemed as though he regretted having gotten on the elevator with me. He opened his mouth and appeared about to say “I don’t know” while just as quickly realizing that he’d have sounded foolish if not rude for answering in such a manner. His mind seemed to race through ways to avoid answering my inquiry, albeit fruitlessly; so, resigned, perhaps, his voice hollow, he said, “Eleanor.”

I nodded, surprised, despite myself, at having gotten this much information; then, sensing that I might be on a role and that such an opportunity to ask Fletcher about these things might not occur again soon, I said, “And she lives …?”

Fletcher briefly met my eyes. “Lives?”

“On what floor.”

Fletcher exhaled, but not in relief; rather as someone expecting awful news who’d finally received it, and now was vaguely content to have the waiting over with. His voice distant, and his eyes staring at the wall, he said, “The 5th.”

After a moment, I said, “The 5th floor.”

“Yes, but …” Fletcher appeared to struggle with whether or not to tell me something. “I …” He glanced at his phone. “I’m sorry, Mr. Omouingo. I have to go.”

Deciding I’d taken up enough of his time, and feeling somewhat bad for the guy, I stepped out of the elevator, whereupon the door closed.

• • •

I’m not sure why, but I had to prod myself to go to the 5th floor. Every time I was about to go (I suppose to investigate), it was as if some invisible force held me back.

Also, I had no information about the woman in the tracksuits except her first name—Eleanor. I didn’t know her last name, I didn’t know what apartment she lived in. There were mailboxes in the lobby, but none had names; many didn’t even have numbers (I’d asked Fletcher about this, and he told me that many residents kept their apartment numbers on the mailbox’s inside, for security reasons—which he didn’t elaborate on). And the callbox in the vestibule didn’t feature numbers either: again, for security reasons (according to Fletcher). There was only a speaker and number pad; when a visitor wanted to buzz someone, he had to know that person’s apartment number and then simply dial it; and the apartment’s buzzer would sound. The system worked, as Fletcher had rung me from the callbox to test it the day I moved in. Yet my buzzer hadn’t sounded since.

Then, one Saturday afternoon, I made myself go up to the fifth floor. Maybe I’d see Eleanor in the hallway, perhaps taking out the garbage. Maybe I’d spot another resident (I’d only seen Eleanor and the man in 414). Perhaps I just wanted to see if, as on my floor, the doors only featured even numbers. Whatever my reasons, I summoned the will, overcame that force that seemed to hold me back (psychological or whatever), went into the elevator, and pressed “5.”

The first thing that happened was that, though the elevator stopped on 5, the doors didn’t open. The elevator lingered, as though trying to convince me not to get off. It was a strange feeling; I knew that the elevator couldn’t be communicating with me. And yet, as though to show the elevator, or myself, that I wouldn’t tolerate such nonsense, I pressed the button to make the doors open. After a long, portentous moment, the doors slid open, I stepped out.

At first glance, the floor looked like mine: white floors, walls, and ceilings; black doors. However, unlike the doors on my floor, all of which had numbers (albeit only even numbers), the doors here were simply blank.

Even though I was wary (or was I afraid? Or just worried that someone might see me and ask what I was doing?), I walked to the end of the corridor, down the end of another, back again and past the elevator, down the other part of the main corridor and to the end of the corridor that ran off it. After I explored the entire floor, I confirmed what I’d suspected: none of these doors had a number, each one was blank.

For a moment, I stood there, at the end of the corridor, between three black doors. I took out my phone to check the time. And though I could see the time, my phone had no bars. I tried to access Google; the service wasn’t available. I figured that my phone was acting up, and decided to return to my floor and see if my phone worked there, when I heard a door slam.

I regretted having come up here. This floor was none of my business, nor was the woman in the tracksuit. As I walked toward the elevator, I told myself that from now on I’d stay in my apartment and mind my business. The rent here was decent, the building clean, the maintenance efficient, the view splendid. Granted, there were odd aspects, but nothing was perfect. And as I turned the corner, satisfied with my self-assertions, I saw, standing by the elevator, the woman in the tracksuit.

She gave me a shock, not only because of her sudden appearance, but because she looked at me in a way to suggest that she wasn’t surprised to find me up here but had hoped that I’d have had better sense. For once, she wasn’t wearing a tracksuit; she was attired in jeans, white socks, slippers, and a navy-blue sweatshirt with a faded Champion logo above the breast. Her hair shone, looking washed and wet; she again had on so much makeup to the point of appearing mannequin-like.

I wondered if I could just walk around her and be on my way toward the elevator (for even though I’d more or less come up here to find this woman, now that I had, my nerve had left). But as I neared, Eleanor’s expression intimated that this wasn’t going to happen—at least not until we had a few words.

I slowed down; then, a few feet away from Eleanor (once more catching a waft of sandalwood and jasmine), I stopped.

For a few moments, it was silent except for a barely discernible hum, like a muted wind filtered through an instrument; all but inaudible, yet getting stronger if not necessarily louder. The sound started to make me feel uncomfortable—as was the whole scene: standing on this floor with apartment doors sans numbers; this woman gazing at me with eyes that made me feel as though I’d committed a crime even though I’d done nothing but walk around the 5th floor of the building in which I lived. A shivering heat started to enfold my shoulders.

“Why did you come up here?” Eleanor’s voice, though not loud, seemed loud. Her eyes reflected the ceiling’s lights; I thought I saw in them something like amusement, but it was an equivocal, potentially worrisome type of amusement.

“Up here?”

Eleanor watched me.

“I came …” Then, either because I was unable to think of anything else, or because I didn’t want to say anything else, I said, “To see you.”

Eleanor considered this, and I saw something like distant amusement in her eyes. She didn’t speak, yet I sensed that the threat of danger had passed.

I gestured toward a black door. “You know there are no numbers on any of these doors, right?”

Eleanor didn’t answer; I suppose that I was hoping for another sign of the faint amusement that I’d just discerned, but I saw nothing of the sort; maybe I never had. I felt uncomfortable again—physically, too: cold, yet beneath that coldness, an oppressive heat; not unlike the discomfort one gets when one is ill—yet not like that at all.

“There wouldn’t be,” Eleanor said; at first, I wasn’t sure what she was referring to, but then realized that she was talking about the doors. I waited, thinking that she was going to continue, but she said nothing more.

“No?” I felt like I was in a state of suspension. The urge to return to my apartment still existed, but I felt it through a veil, and standing there, I experienced that eerie sense of watching oneself, as though I were in a movie.

“No.” Eleanor’s tone was matter-of-fact. “There wouldn’t be, because all these apartments, on this floor, aren’t really apartments.” She added, “They’re connected.”

“Connected?”

Eleanor continued to study me. “Yes, they’re … all one apartment, you could say; but that wouldn’t be accurate, either. It’s more as if they’re one … space.”

I thought about this. “So, that means one person … I mean—”

“Yes.”

I considered this, inferring what she meant—or thinking that I did.

“This is …” Eleanor gestured. “All mine.”

I affected to look around once more, but had an uneasy feeling, or a premonition. I suddenly wanted to return to my apartment very badly and be away from this place and woman (and in that moment, I even regretted having moved from my old building, annoying neighbors or not); and I’d all but decided that that was what I’d do—get on the elevator and return to my place—when Eleanor said, “Come.”

I found myself following Eleanor down the corridor, all the while catching wafts of her sandalwood and jasmine perfume, until she stopped at one of the last numberless black doors. There, she took out a key (the key not attached to a chain or to other keys), inserted it in the keyhole, and turned it. The inside of the room, as far as I could see over her shoulder, was dark. Then, the door ajar, Eleanor turned to me with a look that might’ve been an invitation yet also a warning; she then stepped inside, disappearing into the darkness. Fearing I was making a mistake, I followed.

• • •

I woke feeling fuzzy; my head felt numb, dulled. I was lying on my bed, on the bedspread, in the clothes I’d worn yesterday. My blinds were drawn, but light crept through; I feared that I’d overslept—before I recalled that it was Sunday. I reached for my phone: 12:31—and I groaned: not only had I slept much of the day away, but now, because I’d slept so late, I’d have a difficult time getting to sleep that evening; on Monday, I’d go into work exhausted.

I got up groggily and went into the bathroom; while I brushed my teeth, I noticed in the mirror that my skin looked pale. Not anemic, or necessarily sickly; but oddly pallid.

I told myself that my complexion could be the result of several things—perhaps the way I’d slept.

After I showered, I decided to go up to the fifth floor, seek out Eleanor, and ask what had happened last evening.

• • •

As I waited for the elevator, it occurred to me that I hadn’t seen Craig Fletcher for some time. But when I arrived on the 5th floor, that thought was suspended.

The walls and floor were riddled with holes and smeared with black stains, as was the ceiling; and the black, numberless doors were either destroyed and lying on their sides, or no longer there. And though this was shocking enough, what was especially surreally bewildering was that beyond these doorways and fissures was desert: gray sand and, in the distance, bare trees with black boughs and thin trunks, looking not just skeletal, but resembling skeletons. A balmy yet unsettling draft passed over my skin; a scent of sandalwood, jasmine, and something else—seaweed or saltwater—hit me.

I turned and pressed the elevator’s button.

But the elevator didn’t work; in fact, the area was now decrepit; the elevator door, rusted and dented, appeared as though it hadn’t functioned in decades.

I hastened down a corridor of doorways with missing or damaged doors. The stairwell door was ajar, the stairs were covered in gray sand; an occasional black branch lay half buried underfoot; a whistling sound, like a far-off wind, emerged in the distance.

I hurried down to the first floor. The lobby was desolate, decrepit, seemingly abandoned: the floor abused and half-covered in gray sand, the walls riddled with ruptures and stains, the windows shattered or missing. Outside, on what had been Richman Street, was gray desert, with no sign of the world from before, except remnants of the wooded area across the street; or these might’ve been the same skeletal trees that I’d perceived through the 5th floor’s ruptured walls.

A noise came from the vicinity of Craig Fletcher’s office.

Hesitantly, slowly, I made my way over, as the distant whistling continued. As I reached the off-white, granite floor, now mostly covered in gray sand, between his office and the broken windows, Craig Fletcher emerged from his office—without opening the door, as the door was gone. He was dressed as usual—brown shoes, khakis, buttoned down shirt—albeit he wore a backpack.

He slowed when he saw me; his anxiously determined expression became nervously apprehensive—but, not a moment later, his face showed something like relief, resignation, or surrender. I wasn’t sure, I didn’t care; but I was happier to see Craig Fletcher than I’d ever thought would’ve been possible.

He looked at me, as though waiting for me to speak first.

I gestured uncertainly. “What … is this?”

Fletcher looked about, as though observing 49 Richman Street for the first time. “Well …” He hemmed. “It’s—”

But the whistling reached a new crescendo, and, from the direction of the elevator, came an explosive roar of plaster and wood cracking.

Fletcher glanced at the elevator. “We better go.”

I stood there: I thought not only of my apartment and possessions, but of my job, my—

“Come on,” Craig said; for the first time since I’d known him, he sounded, if not confident, then resolute.

I followed him out through the automatic doors, which were stuck open. There were no other people around, and no sound but the distant whistling. The gray sand covered everything, creating bumps and outlines of, possibly, objects and other things. But in the place where I’d parked my car, there was only sand. I took out my phone: no bars, no signal—not even the time.

“I don’t …” I said, as we trudged up what once was Richman Street; but Craig simply gazed straight ahead.

We walked over gray sand, toward something in the distance. It might’ve been the sun.

Copyright © 2025 by S.F. Wright