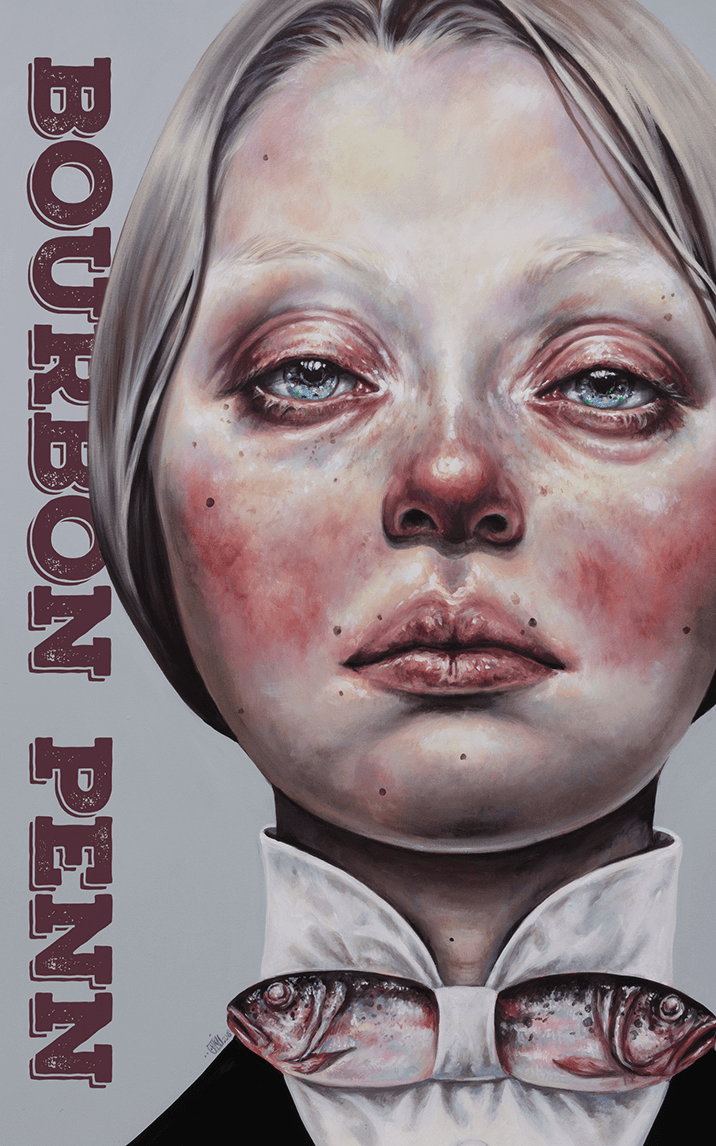

When You Stop Seeing Ghosts

by Sam Rebelein

It’s a big deal in my family when you stop seeing ghosts, except we call ‘em spookies. It’s like getting your first period, except nobody in my family celebrates that. Maybe people in other families do. Does yours? When I got my first period a couple months ago, Mom stared all blank at the underwear I’d bled into. Then she gives me this big crazy grin, and she goes, “Well … Lemme know when you stop seeing spookies, Molly. You wait for it. It’s such a big deal to stop seeing spookies.”

Gee, thanks a lot.

When my older brother Kyle stopped seeing spookies, he was fifteen, and everybody came over with balloons and cake and envelopes of cash. All the aunts and uncles. Like a bar mitzvah. They kept saying, “You’re a man, now, son.” Clapping him on the shoulder and shit. We had a big table set up outside. Hamburgers, hot dogs, potato salad. Mom even set places at the table for everybody in our family who has killed themselves. All these ceremonially empty plates and pictures of the dead taped to the chairs. That’s the weird thing about our family—lots of us end up killing ourselves. And then we just … hang around. We stand in the playground at school. We sit at the end of the slide and wait for you to come down. We sit at the table at the places that have been ceremonially set for us, even though we can’t eat anymore. We just sit there watching everybody else eat. We perch on the edge of the bed or the bathtub. Linger in doorways.

Ya know. Spooky stuff.

Nobody could see the ghosts at Kyle’s party except my younger cousin Tara, who’s nine, and me, who’s thirteen, and my other cousin Bethany, who’s, like, two. She kept crying because my dead uncle Vic kept staring at her from the swingset by the fence. I was rolling my eyes and calling her a scaredy-cat, but then Grandpa Henry showed up inside the fridge and gave me a good jumpscare. I almost dropped the lemonade pitcher. I told him not to do that, he practically gave me a heart attack, but he just blinked at me over his knees. I reached right through him and put the lemonade back on the shelf, closed the door on him. Spookies are cold when you touch ‘em, so my whole arm felt numb for the rest of the day.

It was a good day though. Dad even let Kyle try a beer. Kyle was all smug about it. He had that big crazy grin and wide eyes. Everybody in my family gets that look. Like they all feel a little crazy, or they’re being hypnotized by some Batman villain. You can almost see the spirals in their eyes, and it’s like they can only mostly hear what you’re saying.

Weird.

Anyway, Kyle told me I’d be an adult one day, too, when I stop seeing spookies. Then maybe I could try a beer, too.

No thanks. I’ve tried beer, and it tastes like fuckin’ barf.

Everybody in my family sees spookies from the time they’re born. You see them perched on the edge of your bed, in corners, down the hall when you get up to pee after midnight. They stand there with their heads leaned forward, shoulders back. They’re sopping wet and heaving, like they just swam a long hard way. They pant and lick their lips. But they’re silent. Whatever they’re trying to say, you can’t hear it. Even when I saw Grandpa inside the fridge, he kept gulping air, like he’d just finished a marathon. But I couldn’t hear a sound.

Aunt Allie once told me they all look like that because of the river between Here and There, which they have to swim through, just to be seen by us. According to her mom, the river is wide and filled with lost souls that writhe in this big current. They grab at you while you swim. You have to be strong to make it all the way across, to Here.

“Don’t worry, though,” said Aunt Allie, with that same big crazy grin. “They can’t hurt you.”

“Oh, I don’t think they look scary,” I told her. “They look haggard.” Haggard had just been on a vocab quiz, and I was getting a lot of use out of it.

“But,” I added, “I do feel like they’re trying to warn me about something.”

Allie frowned. “No, Molly, they just want to see their relatives. They wanna see how big you’ve gotten! Now put your hand here, feel your cousin Helen kick.”

Then I gotta feel her belly. Gross.

Allie is pregnant now with another baby. “I’m gonna name her Helen after your grandma,” she says, which is weird because I keep seeing Grandma in the back of my English class, and she doesn’t seem like anybody I’d wanna be named after.

Anyway, I turn fourteen soon, and I still haven’t stopped seeing spookies. They show up in mirrors, in windows, in line at my school’s cafeteria. They’re all soaking wet and heaving, gaping at me with those wide eyes. Glaring through their bangs and shit like that girl from The Ring. They don’t really interfere with my everyday, but they are a constant presence. In fact, I see spookies an average of nine times a day. This is an exact figure, too, which I know because I spent five days counting, and then calculated the exact average, which came out to 9.3, and then I rounded down.

I’m really good in school.

Mom says when you’ve gone a week without seeing any spookies, you’ll know it’s time. You’re an adult now. I keep waiting for this to happen, and it hasn’t yet. Plus, nobody has told me why. I mean, why I want it to happen. Like, why does it matter? What about me changes exactly? How am I not an adult right now? It’s like if all of a sudden you never saw another bumblebee again. They aren’t necessarily part of your life, but they are around. And what would you do if you stopped seeing them? How would that make you an adult? Why does anybody care?

Like, “Mom, where did all the bumblebees go?”

“Ohh you don’t see them anymore? Great! You’re a woman now, Molly!”

So dumb.

Nobody in my family explains anything. Not why we see the spookies, or why so many of us kill ourselves. I even asked one time why so many people in our family have killed themselves. My parents wouldn’t say. Kyle even told me I was a fuckface for asking such a stupid question, which is real mature. Yeah, he’s the adult, not me. I asked Aunt Allie and she wouldn’t say either, just told me to say hi to my cousin Helen again, even though Helen is still sleeping in her stupid belly and can’t hear shit.

“Suicide isn’t a nice thing to talk about,” Allie told me.

“Actually, we’re not supposed to say suicide anymore because it implies that killing yourself is a crime, which it isn’t.”

Allie didn’t know what to say to that. She just grinned all crazy and touched her hair.

So whatever. I’m fine with the ghosts. I just can’t shake the feeling they’re trying to warn me about something.

• • •

And then, all of a sudden—one day, it happened. I didn’t see any ghosts. And I don’t mean like the average dropped from 9.3 to 8.whatever, it just … stopped. I woke up in the morning and it was over completely. It totally freaked me out. I spent the whole day nervously looking around corners and shit, trying to see some spookies, wondering where they were. In school, I kept peering under my desk, wondering if Grandpa or Uncle Vic might be hiding under there. Nothing. I kept looking all day, but by the end of third period, I was already like, Uh oh. Because I knew what it meant.

I didn’t tell my parents about it after school, or the next day. I didn’t see any spookies then either. Or the day after. Or the day after that …

Now I was scared. I couldn’t sleep. I kept staring into the corners of my room, down the hall, waiting …

Nothing.

I felt lonely all of a sudden. Like all my friends had moved away. If it was such a huge effort to swim from There to Here, did they just, like, decide to stop making the journey for me? Did they not want to see me anymore? Like I said, it’s not like the spookies were a huge part of my life. I mean, we didn’t hang out, obviously. But their absence made me feel incredibly weird and empty. Almost sad.

I didn’t know what to do.

And then, after about a week, I started to see … the other thing.

The other thing appeared in corners, around doorways. It curled its thick green fingers around doorjambs and around the mirror from the other side as I brushed my teeth. It peered up at me from the drain, running its tongues over its fangs. The other thing followed me around at school and whispered to me in Latin. The other thing would flex its scales as it hunched on my shoulder, and nudge its nose against my ear as I took vocab quizzes and tried to pay attention in class. The other thing purred on my chest as I slept. Except I didn’t sleep. I could barely do anything. The other thing was too horrible. Much more horrible than the spookies. It stank and it oozed and it breathed sulfur on me like a giant panting dog. It kept chanting shit in Latin and then very quietly saying, like a fat slug with a smoker’s cough, “Capeesh, baby?”

Mom asked me what was wrong at breakfast one morning. I could barely hear her over the other thing tickling my chin with its claws and cooing in Latin. I didn’t want to tell her I wasn’t seeing ghosts anymore. I didn’t want to have that big celebration when it would only be celebrating this big ugly other-thing I suddenly had. It didn’t deserve a celebration. It took my spookies from me, changed the layout of my world. Ruined it, even, I’d say. But I didn’t want to tell Mom about any of that. She’d only be proud.

So, I forced a big grin and said, “Nothing. I’m fine.”

I knew my eyes were too wide and my smile too big. I knew I looked crazy. She’d see right through me.

But to my surprise, she gave me that same look back. She stretched out her cheeks and bugged out her spiral-eyes and said, “Awesome. That’s good, dear.”

And then I realized why everyone in my family looked like that. Such big eyes all the time. At some point, they’d all stopped seeing ghosts and started living with … the other thing.

I had a hard time paying attention in school after I realized that. I kept staring around at the other kids, wondering about their families. Did they all have their own spookies? Did they have … other things, too? What were they like, those other other-things? Could I maybe see any of them? Could any of them see mine?

I hunched my shoulders up and concentrated on my vocab work whenever these thoughts got too intense. I’d blush and feel all embarrassed, and the other thing would slither its tail round my neck and whisper Latin in my ear in that hot hush of breath.

“Capeesh, baby?”

• • •

Despite myself, I have grown rather fond (a vocab word) of my new cousin Helen, who is due in a couple months. Aunt Allie is annoying, but she’s also the relative we see most often. She always comes over for wine nights with my mom, so they can grin and nod silently at each other across the kitchen island, big spiral eyes spinning. At first, every time she came over, Allie made me feel her belly, which I always hated but always did, and then suddenly—I didn’t hate it anymore. Which I only realized because I kept my hand on Allie’s belly until she literally physically pulled away from me.

“Okay, Molly,” she said. “Personal space.”

Why did I do that? I wondered. But I realized it was because Helen was the only one in the family now, besides my cousins Tara and Bethany, who didn’t have the crazy eyes.

I mean, geez. Think about that.

I’d lay awake at night thinking about how horrible Helen’s life was going to be, when she stopped seeing spookies and started to see … the other thing. I thought about it every time Allie came over and I got to imagine little Helen in there, swimming around, eyes still shut and cute and innocent. Then I’d lay awake and worry all over again.

And at some point, after thinking about it for nearly a month, I decided I needed to warn Helen. Try to tell her about this whole “being born” thing.

So I jumped off the bridge by our house. I was surprised by how it felt. Very painless. It was like the water clapped up against my body in this cold solid wall and then my eyes flew forward into the water, which didn’t move at all, didn’t even ripple. Just clap and I flew down. When I turned around, I could see my body staring down at me. And then I sank into There.

Everyone in my family has always referred to the places of the Living and the Dead as Here and There respectively. Except now I am Here, and they are There, a shift in vernacular (another vocab word) that has taken some getting used to.

It was an easy decision to make, except I will miss school.

But now Here I am, floating around in the dark. And I have a mission. I am swimming across the river every chance I get. Been doing it for years. Showing up in Helen’s school, her bedroom, the toy store, the tub—trying to warn my brand-new cousin Helen about the other thing, before it’s too late. Before she goes from spookies to … something worse.

But how can I warn her when I can’t speak? When everyone in our family teaches her to ignore me? I couldn’t even figure out what the spookies were trying to tell me and I’m, like, really smart. So how can I possibly impress upon her the importance of not allowing herself to see … the other thing? This thing more horrible by far than the spookies? It’s not a big deal to be an adult. It’s the other way around, dude. Helen! Wake up!

But how can I possibly explain that to her, when nobody in our family will talk to her? When everybody keeps grinning and saying, “Just wait for it, Helen. It’s such a big deal to stop seeing spookies.”

Copyright © 2021 by Sam Rebelein