Quiet Heaven

by Charles Wilkinson

They’ve been on the road for almost four hours and haven’t spoken to each other since they stopped, for the briefest of breaks, at a service station outside an anonymous town in the Midlands. Andrew enjoys driving, or at least he hates it less than Lavinia, who is in the passenger seat beside him, her headphones on. Although her posture suggests sleep, both her eyes are open, fixed on the landscape unfolding in front of her. She is drenching herself in scenery. When they first met, he’d wondered what she listened to on her MP3 player and the old Walkman to which she was so attached. She’d passed the headphones over and he’d put them on. No music, no words: simply a single surf-like note: a wave suspended in the moment before it curls and crashes into spray on a rocky coast. He’d thought there was something wrong with the recording – or the machine. She explained: over-sensitive to the audible realm, sounds that happened suddenly and without warning, music for her was a territory of suffering. Familiarizing herself with a piece came with a steep price of pain, as well as nothing in the way of appreciation, and was therefore pointless. And there were days, if her condition was at its most acute, when even the sounds of everyday life – a car braking abruptly, the delivery man knocking on the door, conversation that was too shrill – were a torment to her. The best remedy at such times was to play a counter-noise – a note that was sibilant, suggestive of water, was preferable as a way of providing relief from the anguish of a world ravaged by resonance.

Now they’re in the apple orchard county, the second least densely populated in England, the traffic dwindles to a trickle of saloon cars, an occasional tractor. Andrew is more aware of the fields and woods around them, the epitome of the gentle pastoral, and so it’s a shock to see a field, sumptuous in green, scarred in the middle by low mounds of red-brown earth, an infallible indication of a mass burial. It’s a moment before he recalls that foot and mouth disease is once again prevalent. He considers drawing Lavinia’s attention to it but leaves her to contemplate the unmarked meadows to her right. When he next looks at her, her headphones are off and she’s inspecting a map.

“It’s not far from here. Take a left and then a right.”

A moment later, they are parked outside a half-timbered house, its beams a natural brown rather than painted black. The layout of the surrounding buildings suggests it is a former farm. There are no indications that the place is a hotel.

“Are you sure this is right? It doesn’t look …”

“That’s the whole point. It’s not open to the general public. I found it through the Associates of Silence. They keep a list of suitable places to stay.”

Andrew is reminded that he has known Lavinia for slightly less than a year. There is still much for him to learn about her. He has never heard of this organisation.

“Are you a member?”

“Of course.”

Her tone forbids further questioning. As they check in with minimal formality, Andrew reflects that although her reserve is a great part of what draws him to her, she remains a riddle, mysterious even for a relationship of short standing. It is no help that he too has always been taciturn, his previous affairs always prone to foundering on the rock of his perceived withdrawal of emotion. A colleague at work had described him to his face as laconic but not witty. A comment that he’d not dignified with a retort.

As they unpack, he’s aware of how hungry he is. With roadside restaurants and pubs abhorrent to Lavinia, neither of them has eaten since breakfast at home.

“They do food here, I hope?”

“Yes.”

He glances at his watch. “Well, shall we go down?”

“They’ll bring it up once we’ve ordered.”

He recalls her aversion to the clatter of cutlery; even the hum of the most reticent of conversations was an abomination to her. But she must be hungry, for she’s studying a menu bound in black leather.

While he’s waiting, he notices there’s much that appears wrong with the room. Its width is smaller than the large wooden door might have led one to expect. Although ceilings in medieval buildings are often low, he’s found himself stooping despite being far from tall. The windows, which are double glazed, are flanked by shutters: wrong for the period. And there are no exposed beams. The walls must be sound-proofed. As he walks across the room to take the menu, he’s aware that the creak of the floorboards is being stifled by the deep carpet.

Once he’s chosen, she orders on the phone. “It’ll be ready in half an hour.”

“I’ll take a stroll round the back, I think.”

He gestures toward the door, but at the same moment he knows that she will not join him. It is one of her worst days. Even birdsong would be abhorrent.

Outside, he stops, listening for traffic. The house could be no more than a quarter of a mile from the main road, but there is nothing, not even a distant hum; but then the garden is surrounded by high hedges and the side closest to the highway is screened by a stand of beech. Whoever designed it has created a space refined to quietude: windless, without even a hint of a breeze to ruffle the close-cropped greenery, or a single gravel walkway to crunch across. There are no water features; the plants are squat and sturdy, selected perhaps for their resistance to vibration. At the far end, there is an old dovecot, although there are no signs of doves or any other birds. To one side of it there’s a red-brick wall half covered in climbing rose bushes, and then in the corner a potting shed, wooden and painted in green. The scene is somehow suffused with expectation, the imminence of an event that may prove resistant to understanding. Very slowly, the door of the potting shed opens, and the head of a young boy appears. His hair is blond, dishevelled into disorderly tresses, as if he has just run his fingers repeatedly through it. With half a smile on his face, he’s staring straight at Andrew. Then he raises his finger up toward his chin so that it stops just below his lips. Hush, he could be saying, but there is no speech, no sound, not the least sibilance to disturb the sovereignty of silence.

• • •

Almost a year previously, Andrew slipped away straight after work. He’d no wish to join the Friday evening session with his colleagues at the noisy pub nearest to their office, a place so crowded that the customers spilled out onto the pavement. He was always the first to leave, usually after a single pint. After being told to ‘knock the dust off your wallet’ he learned not to accept or buy drinks, thus obviating the need to stay on in order to buy his round.

He crossed to the far side of the street and joined the throng heading for the Underground. A group from his company were gathered near a lamppost, a few of them raw-faced fleshy young men with strawberry-blond hair. They favored blue pinstripes and colored shirts with detachable white collars. One of them had taken off his jacket, revealing a pair of red braces bright as fox-blood. As he talked to a young woman in a black secretarial suit, his voice carried across the crawl of traffic. Nobody waved at Andrew to come over and join them, although someone he knew in accountancy stared in his direction before turning away to talk to a friend.

A moment later, he was safely down a side street, walking through a district he knew less well. Here were bespoke shoemakers selling conker-colored brogues polished to a gleam and small art galleries with pictures in elaborate gilt frames displayed in the windows. It was quiet. In the early spring sunshine and with the weekend ahead he felt the buoyancy of having escaped. But now he was moving into unknown territory, closer to the river. There were terraces of eighteenth-century houses, a few residential, but most with brass plates next to the brightly painted doors. At the end of the street he saw a building in pale orange brick with arched windows in the Romanesque style. Beyond the black railings were steps leading down to a basement. The door was open and an A board was positioned to one side. To the right and on the same level as the basement, there was a small garden with a magnolia, its blossom white with the radiance of spring. A few wooden chairs and tables were grouped around the lawn, but there were no customers. No doubt the place was a restaurant or bar. It would be pleasant, he thought, to sit outside, enjoying the sanctuary with its tree and flowers.

Inside, the light was subdued. At first he thought it was empty, but then he made out first one customer and then another, both seated in alcoves. As he moved closer to the bar, where a man wearing a bowtie was reading a newspaper, he saw that although the tables in the center of the room were unoccupied, there were at least seven or eight patrons, all by themselves, drinking in various corners and dim recesses. Most were reading newspapers or books, but there was one, a portly man in shirtsleeves who was examining a ledger.

As Andrew approached the bar, the man in the bowtie looked up and raised his eyebrows, as if surprised to have his reading interrupted. Andrew stood quite still, incapable of ordering. The man put out his right hand, the palm upwards.

“He wants to see your card.”

The voice, so soft as to be only just audible, came from behind him. He swung round and saw a woman in her late twenties, her dark hair cut short in a style Andrew assumed to be French. She was simply dressed in subdued colors, apart from a light blue scarf. Her face looked marmoreal, the skin smooth and unpowdered.

“What card?”

She raised a finger to her mouth, pursing her lips for a sound that never came. Then she stepped close enough to whisper in his ear: “If you want to talk, we’ll have to go outside.” She gestured at the barman, as though to say he’s with me and pointed at a wine bottle on the shelf behind. Then she steered him through the double door and into the garden.

“Thanks for rescuing me. What was all that about a card. Is this place a club?

They were seated close to the magnolia. Some of the petals, splashed onto the grass, gleamed like snow.

“No, it’s not a club. But you do have to be a member if you wish to drink inside during the Quiet Hour.”

“I’ve never come across that custom before.”

“Some places have a Happy Hour; here they have a quiet one.”

The barman brought out their bottle of wine and poured. Far above, a jet slid soundlessly across a glassy sky. The contrail was still for a moment, as if sprayed onto a smooth surface, and then began to widen and dissolve.

“And so why, if you wanted to sit in silence, are you out here talking to me?”

She looked at him. Her eyes were too large for her age. Her gaze was sharp but had a child’s candor. He noticed that the blue of her irises was almost the same color as her scarf.

“I like your shoes.”

“Oh?”

“And the way you walk in them. Not clomping around like some men. It’s not often that Joseph doesn’t look up when someone comes in.”

“Joseph?”

“The barman. I think you’d be perfect for the Quiet Hour.”

The tall apartment block on the other side of the building muffled the clamor of the city, the screech and growl of engines, the clattering footsteps that hurried to bus stops and stations, the cries of news vendors, all of which merged into a continuous hum, superimposed with the rips and tears of higher notes: screeching brakes, tire squeal. Although the garden was overlooked by several high buildings, the sun found an angle to sneak a soft apricot light through.

“Do you live alone?”

“Of course.” For the first time, a smile, which seemed to belong to someone else, crossed her features. “And so do you. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be talking to each other.”

“Have you found a quiet place to live?”

“Quiet is never quiet enough, don’t you agree?”

“Yes. I’ve moved three times in the past year. There’s always something not right wherever I go.”

They were both flat dwellers, being too poor to afford the down payment on a house in the capital. Work and traveling on public transport were, they agreed, forms of atrocity. Conspiracies against solitude. Neither wanted anyone to make a claim on them; they would always be content to live by themselves. Yet occasional companionship was a solace. In parks where few people gathered and in the hidden woods of north London, they discussed their desire for silence, their hopes of a different life in the country.

• • •

Helped by half a bottle of red wine, Andrew has slept well. Once he thought he heard a creak in the corridor; at three, there was a plaintive cry of an owl. But when he arrives in Lavinia’s room for breakfast, her pallor is another shade closer to sleet, the circles under her eyes inked in, her whole face wounded by insomnia. Somewhere close by, she complains, there were animals, moving about in the fields. A bird clattered against the windowpanes. Whenever she is in an unfamiliar place she always sleeps badly.

“I thought you’d stayed here before.”

“No, it was recommended in a newsletter.”

“The Associates of Silence?”

She nods and begins to pour coffee. He will not speak until the caffeine has had time to do its work. Until now he has not seen her early in the morning. Although they discussed, many times, staying in each other’s flats, just for one night over a weekend, their deliberations have remained at a theoretical level. This is the first time they have been away together.

Her blue eyes darker than normal, she turns toward him: “Do you … like it here?”

He pauses. Always mindful that her condition is worse than his, he’s careful not press her to stay, even though they have barely arrived. His suitcase is half unpacked. And then there is the boy in the garden, the son of the owners, he presumes.

He hasn’t told Lavinia about him; for her, children always came well qualified in the creation of noise.

“We’re in prime agricultural country. There’s always likely to be some … disturbance.”

She continues to drink her coffee, holding the mug in both hands. “There’s somewhere else. A place I know in Wales. It’s quite a drive, but we’re close to the border here.”

“Oh?”

“Yes, it’s in a valley. There are the ruins of an old priory. I’ve always believed that if you want to discover a quiet spot you should find out where the contemplative orders had their houses.”

“The Trappists?”

“Perhaps. Even better were the Carthusians.”

“And the house you mentioned. It’s not another hotel?”

“No, it’s a private property, but the owner’s away at the moment.”

They leave after lunch. Lavinia puts on her headphones and presses play, retreating into a single note made by the sea, which will submerge the sound of the engine, the hiss of passing traffic; soon it will become, if she is fortunate today, part of herself, something registered rather than heard, barely noticeable.

Again, Andrew sees the long red-brown scars in the pasture, the churn of disturbed soil, the tire tracks made by tractors and diggers. There are no cattle in the fields, only sheep.

He has been driving for half an hour when he slows down: black marks ahead of him on the road. For a moment, he thinks they are molehills, erupting through the tarmac. But as he comes closer, he sees a wing tip, raised skyward. And then a beak. He stops the car and gets out. Lavinia takes off her headphones.

“What’s happened?”

He bends down on one knee. The feathers have a purple-green sheen, ineffectual armor against whatever has caused them to drop from the sky.

“They’re starlings.”

“What can have happened to them?”

“I don’t know.”

He climbs back into the car but cannot bring himself to put it back in gear. For a minute, he sits quite still, both hands clasped on the wheel, motionless in the presence of an unfathomable calamity. He does not want to drive straight on, despoiling them further, but there are too many for him to sweep them all to the side of the road. Lavinia has put her headphones back on. He can just hear the monotone of surf-hiss. There are fewer dead birds on the verge. He turns the vehicle to the right, until he is hard by the hedge, and drives bumpily on.

It’s late afternoon by the time they arrive in the valley. Instead of the stark mountains of deep Wales, there are wooded slopes and a stream zigzagging over gray stones. At the top of a hill the arch of the abandoned priory is visible through a fretwork of branches lightly adorned with leaves. There are no signs of any other buildings.

Lavinia points to a turning, more a track than a road: a green arcade; the boughs, intermingling foliage, almost blocking out the sky, the space quivering with filtered leaf-light. As they climb further up the hillside, the wood on the right-hand side thins. There are glimpses of the neat rows of Forestry Commission conifers, new growth spiked like railings, and blue-grey mountains beyond.

“We’re almost there. Take the next right.”

They round the corner: a drive, patchily graveled; a white building with a flat roof, its appearance Mediterranean; a terrace and a lawn, extravagantly overgrown, the grass gone to seed, invaded by nettles and dandelions, leading down to a wooden summer house.

Inside the rooms are airless, rank with the odor of dead plants. In the living room, dead flies and wasps have made a mortuary of the windowsills. Past summers have bleached the spines of the books on the oak shelves. There’s a faint smell of foxed paper and dust.

“Who did you say owns this place?”

“I didn’t. You don’t have to worry about him. He’s away most of the time.”

The fridge is empty, gray-black with bacteria. He’s glad they stopped to pick up provisions at a small market town on the border. While she arranges the salad on plates that have had to be washed first, he finds a corkscrew and opens the wine.

They are both tired after the journey and he waits until after the meal before he speaks.

“We’re certainly secluded. No fields with noisy livestock; just this house halfway up a hill. A dead end. So no neighbors further up, I take it?”

“That’s right. We have the hill and house to ourselves.”

“Who built this place?”

“A classics don.”

“And the present owner?”

“The same man.”

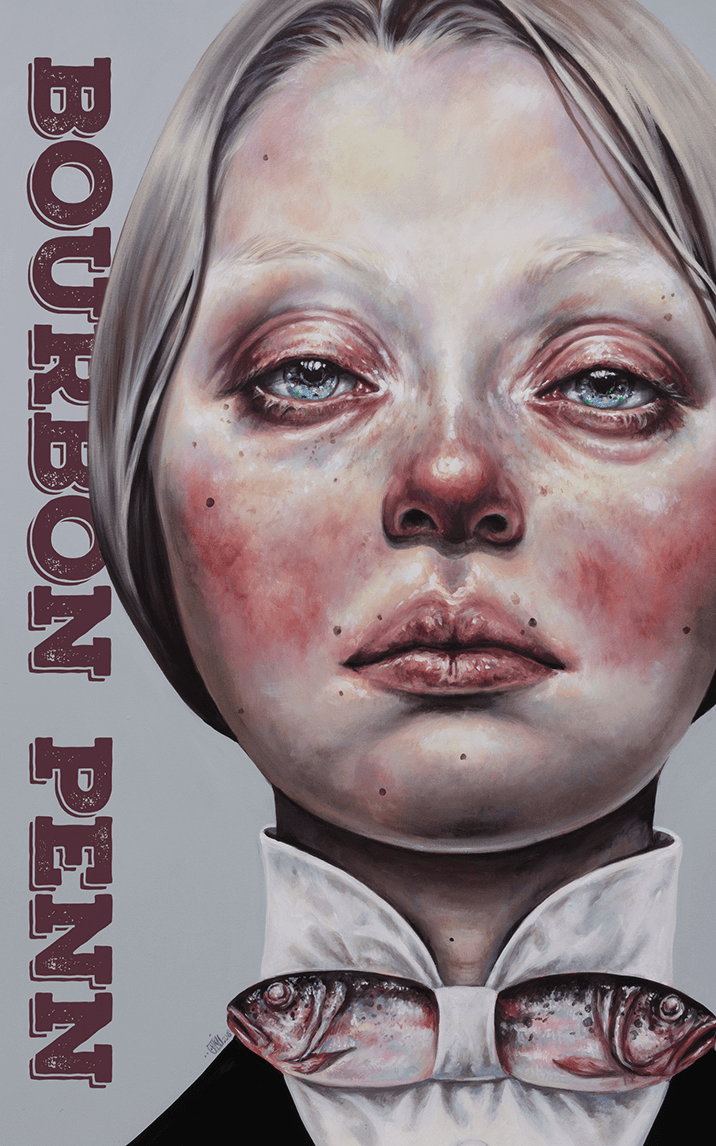

Lavinia, who has drunk more wine than is usual for her, decides to go to bed early. The house is larger than it appears from the outside, Andrew now realizes. There are more rooms at the back; one of which, sparsely furnished but with its own shower, appears to have been reserved for guests. At the end of a corridor, he finds a study: more shelves, this time lined with dictionaries and works of scholarship; a sturdy desk with a green leather top; an anglepoise lamp the only touch of modernity. He’s about to go when he notices a small picture on the wall; a drawing in pen and ink with a wash of watercolor. A boy, his curly hair unkempt, is peering through a rose bush. He is staring straight ahead, a warning in his eyes. The forefinger of his right hand is raised, so that it touches his bottom lip, but his mouth is slightly open, just wide enough to hush the onlooker who breathes beyond the edge of the frame.

• • •

Even when by himself in his flat, Andrew always closed the doors quietly.

He was fortunate to be living in an Edwardian apartment block, built in the days of dense brick walls and solid wooden flooring. Even so, he’d laid a thick carpet over the one he inherited. He had no wish to hear anyone else or be heard be them. Yet somehow sounds drifted in, especially in the summer when the windows were open, and people stepped onto their balconies to water plants or drink wine. The new couple in the flat above had a passion for jazz, played late and loudly. He’d complained, but there were few discernible improvements. Already he could hear them stomping about, although it was early in the evening. The music was bound to start in a minute.

His parents, who’d loathed each other and had a long-standing commitment to expressing it, lived in a semi-detached house in the suburbs. Doors were slammed, even in the middle of the night. Family meals either acted as conduits for recriminations or were taken in a silence punctuated by the angry deployment of cutlery. The whole house seemed to vibrate with rage. It was some consolation to Andrew that he had no squabbling siblings.

Upstairs a shrieking trumpet accompanied gritty vocals. At least Andrew had decided to go out. He’d agreed to join Lavinia for a drink in the place where they’d first met. After a difficult week at work, the open plan office even more of an echo chamber for every audible irritation than usual, he decided to treat himself to a taxi.

When he arrived, there was no sign of Lavinia in the bar. Once again, it took him more than a moment to pick out the customers, men with inward-looking eyes. Dressed in soft browns and grays, they appeared inconspicuous enough to be subsumed into the ochre-colored walls, leaving their half-finished glasses of bottled beer behind them. The fat man, most probably the manager, was still seated at the same table, the ledger open in front of him. The barman gestured to the garden.

Lavinia was under the magnolia tree, its branches now almost bare of petals, although the ground was strewn with them, as if there’d just been a wedding. For a while they drank in silence; it was odd how few cars passed down the road in front of them.

He glanced around the garden. “I see we’re alone again.”

“People come to this bar in order not to talk to anyone. Most people prefer to stay indoors, even when the weather’s warmer.”

He told her about the frustrations of his job, the jabbering and practical jokes that marred his every day at the office. And then to come back to the musical mayhem from the upstairs flat, which was intolerable. For the first time, he told her about his family, the operatic arguments set to a soundtrack of stentorian intensity.

“I was more fortunate in that respect. I inherit my sensitivity to noise from my mother. She couldn’t bear my bawling when I was a baby. I was brought up by an aunt until I was old enough to understand.”

“And your father?”

“A reserved, scholarly man. He required silence for his work.”

“Are they still …”

“My mother died about five years ago.”

“Your father too?”

“When she became ill he dealt … considerately … with her condition. He held the belief that there is no sound in the afterlife. I think his vision of a ‘quiet heaven’ was a consolation to her.”

“And so he’s still alive?”

She took the wine out of the ice bucket and refilled their glasses. “He became … after my mother’s death … more … retired. A less visible presence in my life. But …”

“Yes?”

“He is always there when needed.”

The sun crept down behind a high-rise building. A cold breeze shivered through the garden. They took the almost empty bottle back inside and sat for while at a table in an alcove, the only couple in the bar, yet quite content to spend what remained of The Quiet Hour without speaking.

• • •

Andrew has lost all sense of how long they’ve been at the house. Once a week he drives to the nearest market town to buy essentials: bread, cheese, wine and pre-prepared meals. It is foolish to imagine they will ever return to the city. By now he must have lost his job, but he gave up reading emails a long time ago; the battery on his phone has given out and will not be replaced.

This morning, an hour before breakfast, he spots the man walking on the front lawn again. Seven or eight times he’s seen him emerging from a copse right on the boundary of the estate. Whenever Andrew tells Lavinia about him, he finds him hard to describe, for he has only ever seen the figure from his bedroom window. Once, he rushed outside, only for the man to vanish, as if evaporated by sunlight. There was just the stillness, the dew soaking through the thin soles of his slippers and the birdsong, indifferent rather than alarmed.

“I was surprised that he moved so quickly,” he told Lavinia; “for whoever he is he stoops; has an old person’s gait.”

In spite of her aversion to strangers, she has displayed little interest in Andrew’s sightings, merely acknowledging them with a nod. When pressed, she’d said that whoever he might be, she was sure that he meant them no harm.

And now they were both sitting at the table on the terrace. Their evening meal has been cleared away, but a second bottle of wine has been opened. Lavinia still has her headphones on, which she has been wearing for most of the day to block out the worst of the birdsong. He remembers the starlings. What could have happened to them? He does not dislike birds, but it would better if they were silent. Were there birds in Lavinia’s father’s silent heaven? Communicating by some form of telepathy?

He stretches out his left hand and touches Lavinia lightly on the arm. She takes off her headphones.

“I’ve almost no money left. My card was refused at the supermarket and in the end I had to pay with what was left of my cash.”

“Oh?”

“How much have you got left?”

“It went on the electricity. Remember?”

He looks back toward the lawn, the trees, the ruins of the priory on the hill opposite, the whole scene transformed by the light of early evening, the essence of gold. At the edge of the copse, a breeze moves supple shadows of foliage, showing how nothing is fixed for ever.

“Why leave it till winter?”

He stares at her. What is she trying to tell him? He does not want to know.

“You never explained that picture in your father’s study.”

“The one of the boy?”

“Yes.”

“He’s Harpocrates. The Greek God of Silence. My father thought of him as representing the spirit of this place. A tutelary deity, if you like.”

“And so your father didn’t come here because of the life the monks made for themselves?”

“He thought they were well meaning, but he didn’t approve of all that … singing.”

On the far side of the valley, the declining sun alchemizes the treetops and shines the last of warmth onto the priory’s gray stone.

“I’d like to meet your father.”

“He was here this morning. Left us this bottle of wine. We’ve let it breathe long enough? If we try it, we won’t see winter.”

He lets her pour. Years before he’d read the journal of an artist whose name he could no longer recall. The man had been ill and in pain. On the day of his death he’d downed an overdose of pills with whiskey and then made his final entry, writing until the words were illegible and the pen fell from his hand.

Andrew picked up the glass and drank. There was just enough daylight left to see them through before the embrace of darkness. He stretched out his hand and took Lavinia’s.

“Harpocrates is also a god of hope.”

“Oh?”

“Perhaps the hope for a better place.”

Andrew has not noticed before how the front of the summer house is adorned with roses, prolific and burgeoning, Then there’s a boy’s smiling face at one of the windows. A moment later, he’s outside, seemingly without having had to open a door. Scintillating in his skin, he dances, silent across the lawn and toward them. Andrew tries to turn to Lavinia, but he cannot do so, although he still senses her hand in his. Now there is only the boy in front of him, his finger moving up toward his bright lips, and the mouth changing, opening as if to form the shape for a hush, a sound that does not have to be said.

Copyright © 2021 by Charles Wilkinson