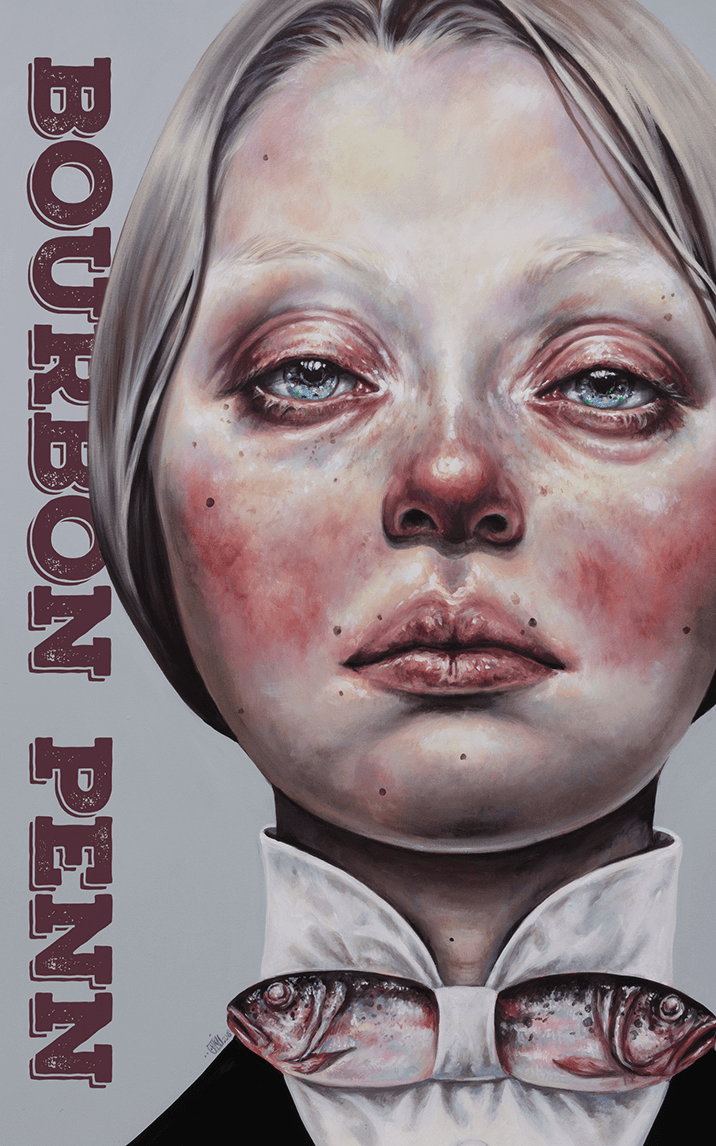

The Belly and the Trees

by Chelsea Sutton

I’m running, or something close to running, with this bloated stomach, inflated, hard as a geode, bouncing against my bladder full of days of diner coffee and tomato soup. I’m running through the outstretched limbs of black oaks and prickly pines, poking into my arms and hair and thighs. I’m bleeding, somewhere, everywhere, and the rain can’t wash it away fast enough before there’s more. The blood tastes like iron and wood and glass in my mouth, but I keep running because I hear her screeching, the thing, the baby, crying and cackling and wailing deep in these woods, and I have to find her. They can’t have her. She doesn’t belong to them.

I’m running and remembering the dream I had just a few nights ago, that the thing inside me was dead. Dead but still in my stomach. It was hard like wood, its ghost trying to get out, its long fingers attached to saws, cutting through my skin.

I never wanted to be a mother.

• • •

Earlier that night, I’m sitting in the corner booth at Farris’ Diner, eating my tomato soup and staring out the window at the forest just across the street. The rain is beating down like mad so I really have to squint to see the edge, and every gust of wind makes me think I see Danny coming out of the forest, finally, after three months. That’s him that’s him that’s him.

But it’s never him.

Everyone’s been acting like Danny was a real nice guy. Like as soon as he disappeared he became a saint, a loveable good ol’boy, a joker, a generous and kind spirit. People can’t get enough of Danny now that he’s not here.

Disappeared people are always the best kind of people.

I don’t mind being married to a disappeared husband.

I have to sit sideways because my pregnant stomach rubs too snug against the table. The neon pink of Faris’ sign makes the rain look like a red sea flooding the trucking route that cuts between me and the forest, me and Danny, if he’s still there.

I don’t know what I’m more afraid of. If he’s there, watching me. Or if he’s not there at all.

A group of alcoholics is gathering on the other side of the diner for their weekly AA meeting, hovering together with their buzzing kind of whispers, like bees, drinking their coffee and sugar.

“Hey, Bo. You sitting in again tonight?” Mark calls to me through the buzz buzz buzz.

I grunt and slurp my soup.

“Just don’t tell anybody my secrets, okay?” Mark says. His voice is sugary. He’s rolling up the sleeves of his flannel shirt, stained and wet from the storm.

I nod and put my hand on my belly. The sound of the heart of the thing inside me is beating so fast the rain can’t even keep up. The beating fills up my whole ears and for a moment I’m drowning in it. Drowning in my blood and its blood, all together.

A tree outside the diner is bowing in the wind, the storm tapping its branches against the window beside me. I can’t help feeling that the tapping is a code, a message from the tree to me, we see you, we’re watching, it says. I’ve always felt that. Growing up in the mountains, in the woods, I thought it was natural, for the trees to watch, to reach out. The way the trees seem to bend slightly around me as I walk through them makes their trunks look like wrinkles in an old man’s smile. The way their leaves brush against each other, like eyelashes. The wind through them, like laughter.

I don’t like being watched. And ever since Danny disappeared, that’s all the town does. Watch and whisper. Poor little girl abandoned by her man. I heard it wasn’t his kid anyway. I heard she threw herself down some stairs to abort the thing. She calls it a thing. You ever hear a mother call her baby a thing.

When Danny disappeared, I tried taking more shifts at Farris’ Diner but Liz, the head waitress, wouldn’t let me, being six months pregnant at the time of my asking. I’ve made a deal with Liz that as long as I do some rolling of silverware and filling of the saltshakers, and anything else she can think of I can do while resting, I can stay all day if I want and I can have as much oatmeal and tomato soup as they got. I can only eat two things while pregnant: oatmeal with heaps of brown sugar and bananas, and tomato soup. Everything else makes me gag.

I hear Mark call out to me again. I remove my hand from my stomach and the beating fades down.

“Huh?” I say.

“You excited? It’s getting close isn’t it?” He’s smiling like it’s his own kid.

“No,” I say.

“No, you’re not excited or no, it’s not close? I thought it was close.”

Liz is placing a plate of donuts on a table in the middle of the alcoholics, and they immediately grab for them. In a pencil skirt and bright pink sneakers, she’s not much older than me. She never asks me if I’m excited.

“Mark, leave Bo alone. She’s got to stay focused. Right, Bo?”

“I’m focused,” I say.

Liz’s smile goes kind of crooked and she just nods at me.

“If you need help, you just call,” says Mark. “You got my number?”

“Shut up and eat a donut,” says Liz.

• • •

Earlier, much earlier, earlier than all that. This is before all that. Before the pregnancy and the woods and the night Liz crawled into bed with me and told me she’d heard the voice too and felt the woods watching her. That I wasn’t crazy.

Danny and I both grew up near the woods, but it wasn’t until our fourth date that we go hiking and he tells me he’s looking for signs of Bigfoot, even though no one ever sees Bigfoot this far south.

In the forest, as he’s looking for Bigfoot, I tell him a story:

I was ten or twelve and I’d been sick for several months. A rash all over my skin, a cough that starts deep down at the bottom of my gut, each cough feeling like I’m trying to turn myself inside out, the top of my mouth covered in bumps and little puss pockets that burst in a satisfying way when I push hard against them with my tongue. I don’t go to school for some time because of this and I’m getting antsy, so I sneak off to take a walk through the woods. My dog, Bruiser, came along, a dog I had found wandering among the trees behind my house and I begged my parents to keep. He was moody and growled but he was mine.

As Bruiser and I round a corner, one of the tallest and oldest trees in the woods falls – crashing right on Bruiser. And not in a boink on the head kind of way. More like a slice right through the body kind of way. Skull cut almost perfectly in two. Blood all over my shirt.

I’m devastated, but soon after, I start feeling better. All my symptoms go away.

The doctors realize that there was a mysterious allergy in Bruiser’s fur, a dangerous irritant that was slowly cutting up my lungs, and if Bruiser hadn’t died, I may have been the one to go.

“It was the trees,” I say. “It was like they knew. Like they were protecting me.”

I still run my tongue over the roof of my mouth when I’m feeling sad or lonely or nervous, looking for a puss pocket to burst, but I never find one. I don’t tell Danny this. I worry he might not want to kiss me if I say that out loud.

Danny listens to my story and nods and grunts. Then he points to the bark of a tree where a chunk of goo is lodged, wiggling, and green.

“That’s Bigfoot saliva if I ever saw it!” says Danny, and scoops the goo into a plastic bag.

I make a sketch of the goo in my notebook as he fumbles with a science kit he’d bought off the internet—cheap petri dishes and beakers he would later fill with the goo and stare at, for hours, noting any changes, any shifts, any smells, even though he didn’t know what any of it meant.

In my sketch of the goo, it is flowing from the gaping mouth of the tree, who stares, wide-eyed and hungry, right at me.

• • •

Later, much later, when we were married, Danny and I had this morning routine all set up—I’d make us omelets or pancakes or toast and jam (before the pregnancy that is) and we’d read the paper and do the crossword together. When he was stumped on a word—which happened every morning, with every word—he’d drum his spoon on the table, drum and drum and drum until I could barely keep myself from giving him the answer. And then he’d suddenly stop and laugh and point at an underwear advertisement right next to the crossword—a photo of a model in bra and panties and spiked high-heels—and he’d say, “Hey, you should be wearing that when I get home.” I never was—but that doesn’t mean I didn’t think about it. He’d go to work at the mechanic shop and joke with the guys about his wife, waiting at home in her lingerie, like a good little wife, and then he’d come home to me, in my waitress uniform, smelling of syrup and garlic butter, finishing the crossword in a dark kitchen under the single naked bulb above the table. He’d grumble and clomp to the bedroom, and sometimes when I went to bed and he was still awake, he’d pull my clothes off and breathe into my neck some mumbling version of I love you without wanting or waiting for a reply, and I’d lie there and sketch something in my mind, a trail in the woods, etched out in boxes, like a crossword puzzle, the words in the undergrowth, dappled with sunlight.

• • •

Later, much later, after I’m pregnant, after Danny has disappeared, I’m out in the woods, drawing in my sketchbook. I’m staring at a clearing in the woods and imagining a house, a real house, better than my apartment over the dry cleaners. The house sits in the clearing in my mind and I’m trying to focus on it but there’s this incessant breathing, this beating of a heart, this humming faraway voice, a constant sound since I found out I was pregnant, since Danny made me keep it. This thing is making me crazy, this thing I never wanted, this thing that is forcing motherhood on me, the word mother and baby, but the thing I keep falling in love with at moments when its heart is beating along with mine, and I think I hear its voice whispering something sweet and nonsensical.

I’m trying to focus on this vision of the house when I feel something sliding across my belly and I look down to see a tree root, snaking up from the ground and curling around me. I leap up and run out of the woods, leaving my sketchbook behind.

• • •

Later, not too much later, when I’d refused to go back into the woods for more than two weeks, I wake to find a thin, young pine tree had grown up overnight, right outside my bedroom window, its limbs brushing the glass and tapping against it in the breeze.

I take an ax from the neighbor’s shed and chop and chop at the tree until it’s down, sideways along the road like a deer crushed by a truck.

Later that day, I’m eating oatmeal at the diner and it suddenly feels like there’s something staring at me, from beyond the spoon, beneath the bowl. I look down and think I see something flitting around in the wooden tabletop like maybe there’s a bug or something, but I wipe at the spot and nothing is there.

Then that evening, as I’m eating my tomato soup, it feels like the table is reaching out and taking my hand, like it’s wrapping itself around, hard and warm. I shake my head and close my eyes.

I drum the spoon on the table like Danny used to do. I try to remember a word that doesn’t exist and the drum, drum drum feels like a spell and I eat the rest of the meal just fine, swallowing tomato soup and my own blood right along with it.

A few nights later, I can’t sleep—the thing is restless and talkative and I’m hating it, I’m wishing it dead. So I call Liz.

Liz arrives, still in her apron and pink sneakers, smelling of bleach and fry oil, and she crawls in bed beside me, tucking the blankets tight under my chin. Liz says she heard those voices too. Before she lost her own baby. After her sister died. The voices that want to be heard, that find their righteousness, that pull you in all directions so you never hear the truth of it.

“What’s the truth of it?” I ask.

“When I picture death, I used to think of the Grim Reaper,” says Liz. “Now I can’t. It’s not a man. It’s nothing like a man.”

“Then what’s it like?” I ask.

“Like a tree,” says Liz. “Like a prickly inner ring of a tree.”

• • •

Later, much later, I’m sitting in Faris’ Diner listing to the storm and the beating heart of the thing inside me, and its far away voice.

“Alright you deadbeats,” says Liz to the AA group. “It’s time. This is a regular meeting of the Clarkwell Alcoholics Anonymous. Let’s start with a moment of silence. Put your coffee down, swallow what you’re chewing, and shut up a minute.”

The group bows their heads together, but I see Mark stealing a glance and a little smile at me.

I glare back at him and look down at my spoon and then the table—and I see a face in the wood top. The face of a little ghostly creature, dark eyes like holes in the trunk of a tree, smiling with saw-like teeth, just watching me from tabletop. It stares at me, its wrinkled chest heaving up and down, its mouth spreading into a sharp bloody grin, its breath steaming up the table, like it was looking into a mirror.

I close my eyes and drum the spoon on the table. Drum drum drum.

“Alight. Serenity prayer. Mark. Go,” says Liz.

“Oh. Sure. Okay. God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to …”

The thing wraps itself around my hand again. I can feel its spindly-like fingers, wrapping and wrapping and wrapping.

I scream. I take a butter knife and start jabbing at the table. Jab jab jab – until it slips and scratches a layer of skin off my index finger.

“What the hell did you do?” says Liz, rushing over with towel. She looks over her shoulder. “I don’t hear a goddamn serenity prayer!”

Mark continues the prayer.

Outside, the trees are battering their leaves against each other, their trunks creaking, sending wooden voices echoing away from the diner, through themselves, deeper and deeper.

I take the towel from Liz and put pressure on my finger.

“It slipped. It just slipped,” I say, but there are marks all over the table and Liz sees them.

Mark calls from across the room. “Liz, should we go on?”

“Yes. Jesus. Do I have to do everything for you people?” Liz glances at me with her face all scrunched up and worried, and goes back to the group.

I spoon up my soup but I can’t hardly eat now, I’m shaking and bleeding and aching.

And then there’s a string of laughter. I look across the room but the AA group is serious and quiet and buzz buzz buzzing with sincerity.

Danny wasn’t an alcoholic. Never touched the stuff. But I always wished he was. It would have made things much easier. It’s something to blame.

• • •

Earlier than that, much earlier.

When I find out I’m pregnant, I don’t tell Danny. I go straight to the doctor.

I ask for an abortion. Abortion. No one likes to say the word, like it has power all its own to terminate something. I say it a few times to the doctor. Abortion. I’d like one, please. I don’t want to be a mother.

“You’ll change your mind,” says the doctor.

“Nope,” I say. “I won’t.”

“Have you talked to Danny about this?” says the doctor.

The doctor knows Danny and me, has known us for years. I thought he would be the one to go to, he would understand.

“It’s not his decision,” I say.

“He’s your husband,” the doctor says.

“It’s not his decision,” I say again.

“I’ll be right back,” says the doctor.

Twenty minutes later, Danny is dragging me out of the doctor’s office, a fire I’ve never seen burning up his face. He takes a detour into the woods and, once we’re out of sight of the road, he grabs my wrists and slams me against a tree, leaves falling around us from the force of him. He takes my face in his hands. Digs in his nails.

He makes me promise not to do that again. He calls the thing a baby. His child.

A spiny limb of the tree is digging into my side, into my stomach. It’s like the poke of a needle, a cut of a scalpel.

He makes me promise three times before he is satisfied. And he pulls me out of the woods. He doesn’t release my wrist for another hour, a bird that might take flight.

• • •

Later, much later, in Faris’ Diner, I feel eyes watching me from the shiny wood paneling of the napkin holder And there’s the thing again, creeping around in the grains. It is speaking but its voice is wind and rain and thunder.

When Liz isn’t looking, I toss the holder into the next booth. I put my hand on my stomach and the heartbeat is still there, but not as loud as usual.

And there’s that feeling again, and I see the thing staring at me from the wooden saltshaker, carved by some local retired woman. Its saw-like teeth cutting against the sides. I try not to look but I hear its breath, and its gnarled voice scratching through the air.

“Mama,” it says. Its laugh is like wood chips thrown onto a blazing campfire.

I close my eyes. I’m shaking.

“I sawed out Daddy’s throat,” says the thing. “Are you happy? Aren’t you glad? Aren’t you excited?”

A sharp pain cuts through my stomach. Without thinking, I grab the saltshaker and throw it as hard as I can to the tile floor. The wood shatters and pieces scatter every which way. With effort, I pull myself out of the booth and kneel by the shards. The thing is there, bouncing from shard to shard, and then to the wood paneling along the bar.

Liz comes running over in her pink sneakers and asks if I’m alright.

“Nerves,” I say. “It’s just nerves.” I’m staring at the thing etch its teeth into glass.

“Aren’t you glad, Mama?” the thing says. “This is what you wanted.”

“No no no it’s not,” I say.

“Don’t lie!” says the thing.

“Bo,” Liz says, her gaze fixed on the wood panels. “Get away from that.”

“I’m fine, I’m fine, I’m fine,” I say. A tree branch is hitting the diner’s front window, whipping hard with the wind.

“I see it,” says Liz. “Right there. Moving. Bo, I see it. Get away.”

The thing laughs and I start hammering at its face with my fist. Splinters are jamming into my skin.

Another pain cuts through me and I fall to my side, glass poking into my face and ribs. I can hear the whole AA group jumping up, chairs scraping against the floor, their boots against the linoleum.

The branch from the tree whips harder against the window and breaks right through. A chunk of sharp wood falls into my booth and knocks over my soup, tomato everywhere like blood splatter.

I put my hand on my stomach and the heartbeat is barely there. Liz and Mark are talking to me, but I can’t hear what they’re saying. I’m being lifted off the ground. Someone is calling 911. But it all feels far away. I’m giving birth, I think.

I’d hoped I didn’t have to give birth. That we’d just stay like this, the thing and I, or that one day it would just disappear, I’d wake up with a flat belly and alone.

No. It’s something else. The baby is going, is gone, but it’s not a birth.

I watch the face of the thing bounce off the shards of wood around the room and hop out to the tree that broke through the window and disappear behind the tree line across the street.

That’s when I hear it. The heartbeat and the crying and the wailing of the thing, the baby, bouncing out the door and into the woods. My stomach has gone cold and still, a bloated ice cube. The thing inside me, she, the baby, my baby, has disappeared along with the creature, out among the trees.

Not a birth. Something else.

I break free from the AA group and sprint heavily and awkwardly out the door, across the street and into the woods. I can hear boots following me but I don’t look back.

The laughter of the thing echoes ahead of me. I see flashes of its face.

“Bo!” says a voice in the air behind me. “You’re going to hurt the baby! Stop running!”

I keep going, following the cackling and the crying and I don’t know if I’m following a monster or my baby or something else, but I know she’s not there anymore, not inside, so I have to follow.

I run and run, or as close to run as I can get, until I reach a familiar clearing.

A clearing with lopsided house, half finished, made of roots and branches and stitched-together leaves. a single light burning in a window.

It’s the house I sketched in my notebook and left in the woods.

Mark catches up to me and puts a gentle hand on my arm. “Bo,” he says. His voice is syrup now, dense and slow. “You’re making yourself sick. Let me help you get back. You’re bleeding all over the forest.”

The light in the house flickers and I swear I hear laughter bounce against its broken windows. Liz’s voice is far away behind me, raising my name over the storm.

“I’ve never seen this house before,” says Mark.

I break away from Mark’s grip and rush up to the rotten door.

“Bo, what is this place?” Liz’s voice sends warmth down my spine.

I reach out and grab the doorknob on the tumbled-down home. I can smell the moss and the mildew and the ash.

I hear the sound of an ambulance in the distance.

I open the door. The trees seem to bend around me to look inside.

The house is dark and wet and hollow. In the center of the room is Danny’s body, white and rigid, splayed like bug, a fragile sapling oak tree growing up out of the floor, straight through his bloated belly.

The sapling is crying and shaking and cackling at the same time.

The voice of the thing echoes around the room. “This is what you wanted,” it says. “We were protecting you. We love you. We love you.”

“It’s not …” I say. I can’t finish.

“We love you,” it says.

“Bo. Bo, what happened to your stomach?” Liz is in the doorway, taking small steps toward me.

I look down and my stomach is flat, even flatter than before, hollowed out, concave, like a hole in the trunk of a tree, like the eyes of the thing.

The ambulance sirens are deafening. Liz’s arms are around me, like roots, like vines, like strokes of a pen on paper, like a roaring sound of a silent tiny heart.

Copyright © 2021 by Chelsea Sutton