Good Night Moon

by Rich Larson

I’m working the Lunar Circus again, which is always a shitshow. Striped tents sprout up all around the rim of the crater like big shivery cakes; eerie carnival music pumps its way along magnetic footpaths, so you can hear it by induction. They give me a stained janitorial jumpsuit and a bright green vacuole, and tell me to get menial.

First task of the night is cleaning up blitzers. A whole crowd tries sneaking in ticketless every year, and every year the Circus finds a new way to fuck them up. This time it was a monofilament spiderweb, too thin to see or even to feel until they get activated, at which point a body becomes cubed meat.

“What a way to go,” says Mack Damon, observing the strewn blocks, blood already frozen and glistening. “Very artistic.”

I’ve worked with him a few years running, now. He always says he’s researching a role.

Our vacuoles slurp away, pocketing the chunks in an artificial wormhole for later resale, if the blitzers’ families really want their own flesh-and-blood back, or for zombie feed. Every so often I swear I can feel the whispery touch of the monofilaments. I hope nobody sits on the trigger.

We work around the rim of the crater, scooping carcass, until we’re all the way to the front gate. A caterpillar bus full of nuns is pulling up. They come every year to protest the perversities, which are myriad.

For instance: the wrought-iron archway is crowned with three transparent pods, each with a performer dancing inside, and each performer has a lamprey cup attached to their abdomens to slowly suck out their entrails if they don’t get enough eye tracking.

The nuns can’t track much, though. They’ve put out their eyes, which they do yearly, and packed the empty sockets with medigel in the meanwhile. Their order forbids sinful sights, so during the Lunar Circus they have to navigate with a little swarm of haptic drones – provided and maintained by the carnival, of course, since a protest always adds spice.

“I got drunk with a novice once,” Mack Damon says. “She said sometimes, after the Circus, they swap eyeballs with each other on the sly. Blue for black, brown for green. Heterochromatic was the thing for a while, all through the abbey.”

“Did you fuck?” I ask, watching the drones usher the stumbling nuns through the gate.

“No,” Mack Damon says. “But she asked me to describe one of the shows to her. The elephant show.”

I shudder. The Lunar Circus is the dumping ground for every dark subconscious impulse humans ever had, which is why so many people want in, and you get numb to it after a while. But the elephant show, for me, is the bridge too far.

A voice vibrates through my suit, vowels crunchy with static. “We got more blitzers on the east side,” it says. “One of them had a biobomb in her. Big mess.”

The last nun in line turns and smiles eyelessly at us. We head east.

• • •

We sift bone shards from blood-stained moondust and talk about the future of film. Mack Damon is determined to be the last movie star in existence. He has this recurring vision that he calls the Grand Finale, where the sun is turning dwarf and humans are long gone, but somewhere under Earth’s carmine skies there lingers a tiny self-sustaining server.

“And inside that server,” Mack Damon recites, “an entertainment algorithm is still making these movies, these cascades of spliced footage and nonsense scripts, all the dialogue parroted by reanimated digital corpses, churning out a full-length feature every demisecond for an audience that consists of one solitary review algorithm.”

“And the dead actor it likes best is you,” I say.

“And the dead actor it likes best is me,” Mack Damon agrees.

“Well, you’re on the way,” I tell him. “Keep it up. Keep grinding.”

I think he must know sometimes, in the back of his mind, that he’s a machine facsimile of an obscure human performer who died centuries ago.

• • •

They have a canal this year, a steamy loop that carnival-goers can circumnavigate in a filigreed boat that is black and oily-looking and propelled by biomechanical kicking legs. Sometimes animatronic foxes pop up out of the water and request sexual favors.

People are throwing all kinds of detritus in, of course. It only gets an hour of smooth operating before its filters are clogged, meaning me and Mack Damon have to open up the bowels. We find broken razors, baby teeth, a chunk of destroyed satellite, a prosthetic intromittum, and an umbrella.

I open the umbrella and inspect its dripping ribs. “Still works,” I say.

Mack Damon expectorates. “I hate those things,” he says. “If it’s ever raining hard enough to warrant taking an umbrella, the umbrella flips inside out and makes you look like an idiot. Idiot sticks, I call them.”

“Those are the cheap ones,” I say. “The fold-away ones. This is a sturdy old bastard.”

We’re not permitted to keep detritus, though, so I toss it onto the pile. Customers are ambling along the edge of the canal. They ogle at us in case we’re part of the show. I suppose we are. If the Circus didn’t want people to see us, they’d have put us in chamsuits instead of coveralls.

“Fans,” Mack Damon says, with a knowing smile, then waves to them. “Yeah, yeah, it’s me. I’m researching a role, so keep it hush-hush.”

They chuckle, confused. Some look hopefully from him to the prosthetic in his hand, and are disappointed when he tosses it, waggling, onto the pile. One asks us when and where to find the elephants, and I hum real loud while Mack Damon tells them.

• • •

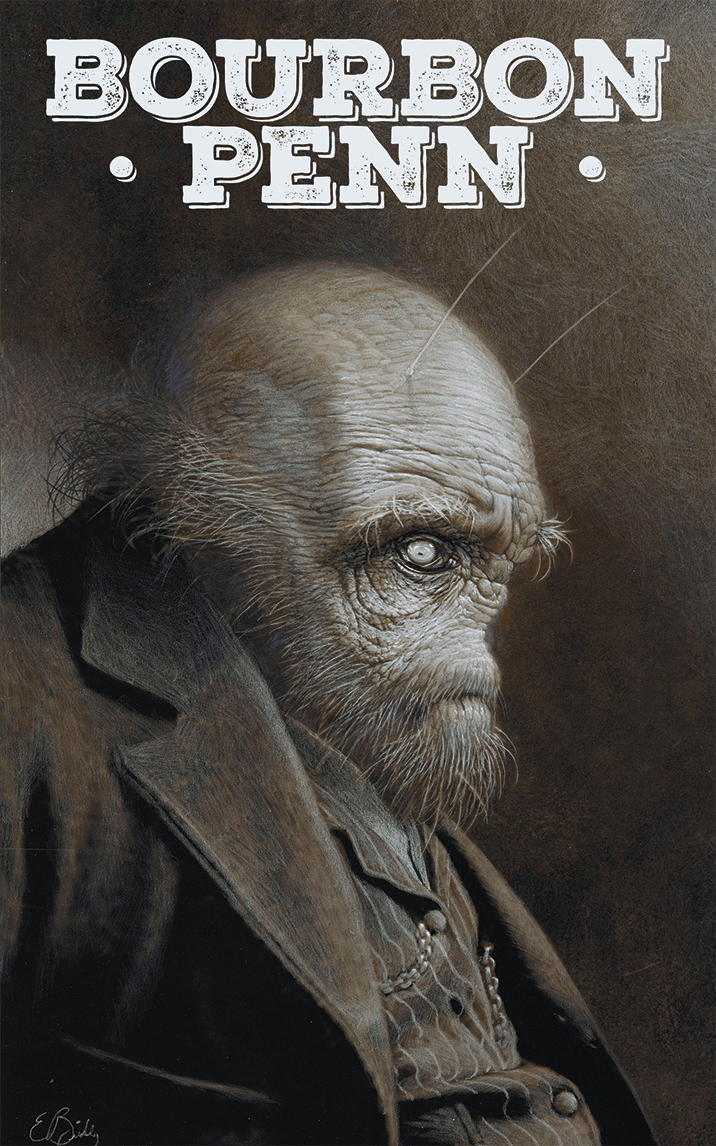

On our break we grab a deep-fried cotton candy pupusa and see a few shows. I never used to like the theatrical stuff, but it’s grown on me, how a fungus does. We watch a weeping man in an antique suit and tie removing his fingers, then watch a production of Peter Pan with child soldiers and nanoshadows and sadistic digital fairies.

The performers are all puppeteered, and sometimes their shifts end mid-scene, or mid-line, so they freeze until someone new climbs up to take their place, then wander off. The transitions are seamless, though. The algorithm is doing a bang-up job.

Mack Damon watches with keen eyes and says nothing, which is his highest praise. The play ends with immolation, all the performers dousing themselves in kerosene and setting themselves alight to become a forest fire of fat and crackling bone. Some insured audience members join in. Me, I’m not contractually permitted to die during the Circus. I don’t think my co-worker is, either.

Break ends right then, which is always suspicious. We unrack our vacuoles and start sucking up the ashes and charred meat while the surviving customers file out. Previews for upcoming shows dance across the fire-scarred stage, advertising Je vous souhaite une catastrophe and Nervous Children Speaking Quickly.

It takes me a while to realize Mack Damon is crying.

“That good, huh?” I ask.

“Oh, no,” he says. “No. Just practicing.”

I can’t tell if that’s a lie or not. Which is testament, I guess, to his abilities.

• • •

The crowd swells as the night goes on. More and more customers come streaming through the neon portcullis, arriving en masse from Dirty Old Earth and various orbitals. I like to observe the yearly shifts in fashion; this time around people of all ages and genders are wearing poofy paramecium skinsuits and prehensile beards.

I see a pair of kids toddling along in inflatable safety membranes, looking like bugs caught in water droplets. “Think those are real children?” I ask. “Or accessories?”

“Oh, there’s plenty of kid-friendly stuff this year,” Mack Damon says. “Like Jesus the Sapient Sourdough. Kids love him. They love how he sacrifices his body for their nourishment.”

We’re spraying down the magnetic walkway where someone’s head exploded. The gray matter didn’t get far. This was a small, personal biobomb, not the big ostentatious take-you-with-me variety, which is why it slipped through the scanners.

Since the person was mid-public-coitus, I figure it was a pleasure bomb, the kind that reads your arousal levels and cross-references prior experiences and takes you out at peak dopamine.

“Here come some sore thumbs,” I say, nodding down the walkway.

Oily black habits stand out amidst the multicolor crowd, but more so than that, it’s the way the nuns walk, solemn and plodding, bearing the weight of the world even in low gravity. The haptic drones do a good job of steering them, though every so often one will trip and stumble into the others.

“You see yours?” I ask. “The one you met last year, I mean?”

Mack Damon shakes his head, looking wistful.

The nuns troop by, chanting prayers. Their packed-shut eye sockets glisten.

• • •

Just my luck, it looks like the elephant show is the Main Attraction this year, the Grand Finale. There are signs for it everywhere, now that the circus is in full swing and all the high rollers have arrived. I can’t bounce three steps without a phantom pachyderm dancing past.

Mack Damon sees me shudder. “That’s why it’s so popular,” he says. “Human-on-human cruelty gets old, but that stuff really gets to you. Really creeps inside your brain and clings.”

“Very clingy,” I say. “Yeah.”

“Hey.” He claps a hand to my shoulder. “How about I clean up the elephant show solo? You can unclog the canal again. Maybe fix that glitchy whore factory.”

I blink. “You don’t mind? It’s usually a two-person job.”

“That’s what friends are for, right?” he says, which aches my sinuses a bit. “Partially alleviating the pain of existence.”

We arrive at the coal pile. Due to an ancient contract between a pre-apocalypse entertainment conglomerate and a pre-apocalypse electric company, still honored by the machine mind descendants of both entities, the Lunar Circus is required to power at least one (1) percent of its grid with burning coal.

It aligns with the barbarity aesthetic real well, so we do it right in the middle of things, shoveling a heaped hill of carbon into an antique pot-belly furnace.

“Remember that screenplay I was writing last Circus?” Mack Damon asks, passing me a metal scoop.

“The star-crossed vet and taxidermist in 2010s New Hampshire,” I say. “How’s it coming?”

“Forget about it,” he says, biting his own scoop deep into the coal pile. “It was deeply flawed. Listen to this new one.”

• • •

The new screenplay is another retro thing, which I think is due to his lineage. This time it’s the 1980s, and a suave grifter type has accidentally stolen a suitcase with documents exposing the covert alien invasion of Earth – sort of a nostalgic throwback, he figures, to when we thought xenocivs might give a shit about us.

“And the aliens are secretly experimenting on us, too,” Mack Damon says, shoveling fast, fueled by excitement. “Remodeling us with their own genetic material. The first hybrid is a famous archeologist, who’s also beautiful. She’s a famous, beautiful archeologist, and unbeknownst to her, she has been exposed to this tailored xenovirus. She starts sprouting feathers. I can picture the scene in my head. At first she thinks it’s a hallucination, but then she starts thinking she’s the reincarnation of an Egyptian deity. She has a tentative grip on reality.”

“Do her and the suave grifter have to work together to save humanity?” I ask, because I pretty much get the gist of these retro things now.

“You bet your sweet ass they do,” Mack Damon says, now churning coal into the furnace at terrifying speeds. “But he’s a notorious swindler, see, so it’s this boy-who-cried-wolf situation—”

“Who plays him?” I ask, just to needle.

Mack Damon looks affronted. “I do, you fuck,” he says. “I play them both.”

I tell him I was only teasing, but he refuses to talk to me or acknowledge my presence even when I lob a chunk of coal at his head. We finish the job in silence, seal up the furnace, and attach the oxygen bulb. The coal burns real good, real dirty. I can almost taste it.

“You have a title in mind?” I ask.

No reply, not even a brow-furrow.

• • •

My co-worker maintains his silence while we maintain the grounds, trimming the hydroponic hedges shipped to the Moon specifically to wither and die. His mouth stays sealed while we seal up a ragged hole in one of the tents’ stripey outer membranes. He doesn’t even scream when the camel-spider we’re feeding escapes its bubble and sinks its barbs into his finger.

But when a voice vibrates through our suits, telling us the elephant show is going to need some major attention, Mack Damon points me back toward the canal. I feel awkward now, but not enough to turn down the favor.

He joins a throng entering the Lunar Circus’s biggest tent. The nuns are going, too, this year. Some of them seem genuinely excited as the drones usher them inside, where by now a performer dressed as ancient electrician Thomas Edison is preparing to brutalize a non-human person. Maybe the sadness is all an act.

I go the other way, toward the canal. People keep pouring past me, all of them jabbering about the elephant and whether or not it is real. The show’s promoters have done really well building up the mystery this year.

The steam-wreathed canal is actually in pretty good shape. No corpses to dredge, not too much trash in the filter. A fox bobs up out of the water and stares at me with beady black eyes. The scratchy recording asks, politely, for a rimjob.

That reminds me about the glitchy whore factory, which has been spitting out a stream of anthropomorphized Venus flytraps, which only caters to about twelve percent of our customers. I’m heading that direction when the Lunar Circus’s biggest tent implodes into a fireball.

• • •

That’s not a normal part of the show.

A scalding shockwave crumps out in all directions, flattening stray carnival-goers to the ground, rippling the other tents. It clubs me down and I nearly fall into the canal, which is now all gushing steam. Warnings flare all through my jumpsuit. Then it’s over, and I look up to see the fire starving, all but snuffed out already.

At first all I think is how they must have taken a cue from the Peter Pan thing, gone all out with actor and audience immolation, but then I think no, there’s no way everybody in there was insured, so then I start thinking accident, and then I remember Mack Damon.

I get that clenched belly feeling, like my insides are wrapping tight as they can around something to keep me from looking at it. I bound over to the wreckage.

All the humans and the elephant are more or less ash. I crunch across the charcoal boneyard, sometimes feeling a brittle sternum or vertebra giving way under my boots. Indestructible implants and jewelry gleam from the mess here and there. I pass the half-melted remains of an enormous articulated godemiche. The buzzsaw is still intact.

When I finally find Mack Damon, he’s been whittled down to his endosteel frame, a rake-like machine with no discernible face.

“Hey,” I say. “It’s me.”

“Hey,” Mack Damon says, and even though he says it through an abdominal port he makes it sound like he’s drowning in his own blood, lots of burbling and gasping. “Hey. What a show, right? What a show.”

“Sure,” I say, squatting down because my knees are so shaky from relief. “What the fuck happened?”

“It was the nuns,” he chokes. “It was those goddamn nuns. They had their eye sockets packed with RDX this year instead of medigel. I saw one of them stick the ignition wire in.”

His featureless head tips backward, and I get a redoubled jolt of fear. “Wait,” I say. “Are you permitted to die here? Contractually?”

He points one claw-hand to his midsection, and I see a jagged hole all the way through, a little tunnel of slagged circuitry. My gut drops.

“This is it,” he says. “This is the Grand Finale, I guess.” I feel a smarting in my eyes, because it should have been me in the tent, because I’m not allowed to die at the Lunar Circus, but before I can say any of that Mack Damon starts gurgling again. “You told me, once,” he chokes, “that this was your dream job. Working the Lunar Circus.”

“I said it was a dream job—”

“Dream bigger,” he hacks. “Dream bigger. For me.” His mushroom-shaped head twists to one side. “Did you ever watch my movies?”

“Of course,” I say, through an aching throat. “Yeah. You were, uh, ubiquitous.”

“Ubiquitous,” Mack Damon echoes, like he is not quite sure what the word means.

Then he’s gone, and I never got the title of his screenplay.

• • •

I wake up on a box spring in the basement suite I rent from a sweetly ruthless little Slovenian couple. My alarm shows 8:13 a.m., which means I worked one hour and thirteen minutes overtime, likely to sort out the aftermath of the suicide-bomber nuns and the elephant show and all the other nonsense now slipping and sliding out of my skull like greased Jell-O.

I swipe the alarm away and thumb over to my email, where the bank transfer from Lunar Entertainments via OneiriCorp is waiting. They really gouge on the dream-to-reality currency exchange, but it’s still enough to pay rent so long as Kraft Dinner with green chilies remains my staple food.

8:13 is still early. I roll over to find some freelance stuff.

Copyright © 2022 by Rich Larson