The Parts of a Shadow

by Matthew Thomas Meade

Thus Children are ever ready, when novelty knocks, to desert their dearest ones… and so it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless.

—J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan, 1911

Peter should have been easy to find. He was just a kid, after all. And, even though he was technically born before me, I was a whole year older than him. Plus he had never seen a city before, so he should have stuck out like a crocus in a patch of crabgrass. I was having trouble though.

I had lost him at the Washington stop near where you could see the water tower through the forest of tall buildings. He looked like he wasn’t going to get off, but then at the last moment, he changed his mind and slipped through the doors, his shadow sliding out the other exit to meet him on the sidewalk. I should have known Peter was going to do that. After all, I knew him better than anyone. By the time Stegosaurus and I got to the next stop, got off the bus and hopped onto one that would take us back to Washington, Peter and his shadow both were gone. The bus shelter was still and empty, the white paint of the posts translucent from the cold.

I had been on Peter’s tail all day. He stalked the streets behind a self-satisfied smile. The house parents from his group home had given him a shirt that spilled off him like loose shingles cascading off an old roof, but his jeans were so tight that I could see his lucky thimble tucked into the pocket. Sometimes he would wear it on a chain around his neck, dangling it in the space between his clavicles. I would watch it hungrily, wanting it, hypnotized by it as it tumbled back and forth on his chest. Sometimes the light would catch it and it would gleam like a big, dumb moon in the night. I would imagine hanging onto the necklace as he leapt over things and dodged around stray animals, as if it were the rope of a life preserver keeping me from going under. But usually, like I said before, he just kept it in his pocket.

As I tracked Peter through the city, exactly 22 paces behind, I kept my eyes peeled for attacks from King Ninja Fairy and his machines. I made sure to keep silent, holding my breath as I pursued, only exhaling when a car passed by, the exhaust smelling like a rotten egg split open. The smells of The World were amazing and beautiful: The hot stink coming from the sewers; the bite on the back of my tongue from the rust of half completed buildings; the accumulated smell of bodies, their scent amplified by the heat.

What people from Neverland call The World:

- The Always World

- The Sometimes World

- The World of Adults

- The World-world

- The City-World

- The Grown-Up World

- The Place to the North

- The World

The day we’d been returned to The World it was Halloween and everyone was dressed like Pirates and Peters and shivering to look like Tink, the costumes piled up on the men did a poor job covering up the pink of their desire. The women hardly wore anything at all. None of them actually looked like Pirates, or Peter, or Tink. Not really. They were drunk and trying to be merry, but instead were crying and throwing up in the street.

We don’t have Halloween in The Never because we don’t have October. It is never brown and dead. It skips right from the wrinkled greens and golds of September to the snowmen and plum pudding of December. It is only ever California or Antarctica. And sometimes it rains.

No one is Christian either, but everyone celebrates Christmas. Neverland is the late 1980s, the lurid colors of those movies and television shows, the dim naiveté of D.A.R.E. programs and school-sponsored dental exams. No one in The Never needs to dress up for Halloween to escape because who would want to escape Neverland? They have already escaped. No one has to “cut loose” by pretending to be a monster or a swordsman because we are monsters, we are swordsmen every day.

What do the People in Neverland Call People From The World?

- Normals

- Normies

- Growns

- Groans

- Northerners

Peter had an altogether different experience with his social worker than I had with mine. He had a man, first of all, who wore a tie and a crisp yellow shirt and who walked on long, storky legs that made him look not just like a Groan, but like an adult. He had been looking for Peter for weeks, having kept a daily slot in his calendar open like a window meant for a lost puppy to return through. The social worker man finally found Peter playing touch football in a nearby parking lot and was able to coax him back to his office. Peter only went with the social worker that day because he wanted to play some mischief, because he was bored and a little curious, and also because his team was losing its game by two touchdowns. When Peter dropped the neon-green foam football and followed the man, his shadow gliding over parked cars and storefronts like the last ice cube sliding from a cup, I stood from where I was hiding and followed them.

I had been to the office a few weeks earlier. I went right after they evacuated Neverland and brought us back to The World. The Never was a place, it turned out. A place to which the laws of space and time didn’t quite apply, but it was a place nonetheless. And it was a place with trees, so the Northerners wanted those since they seemed to have cut down all their own trees. So, due to all that, roads inched closer and closer to the heart of The Never, ships took supplies to the island and resources from it, and trucks pressed the earth down, taming it, wearing it out, reminding it that it was dirt.

I learned all this from my social worker.

She spent a lot of time telling me things I didn’t know. I am not sure why she did that. It just seemed to make her more unhappy.

My social worker was a woman, as I think I’ve already mentioned, but she wasn’t very much like a mother. She looked swollen, like a foot stuck with prickers, and she wore perfume that I guess was supposed to smell like flowers, but didn’t smell like any flowers I had ever sniffed. The Groan who was in charge of me told me I was supposed to go see her, and I went even though I had better things to do. Stegosaurus went with me, but I had him wait outside so they wouldn’t know he was there, so they couldn’t make a record for him too. He slipped around on the outside of the building and tried to get a look in the dirty, oversized windows. I walked into the building and watched the reflection of the lights on the wax floor as they seemed to try to evade me all the way to the door of the social worker’s office.

“Everything is different now,” she explained, “from the last time you were here.”

“Is that so?” I asked her.

“Yes. We’ve had a black president now, for example. A president of Asian descent. And a woman president too.”

“You mean you’ve never had one of those before?” I asked her, almost curious. She didn’t like that.

“I hear you didn’t want to come here today,” she said. “Well I didn’t want to come here either, you know. I’d love to sit around and do nothing, instead of come here. I’m looking for another job, needless to say.”

I didn’t know what I was supposed to say to that and I guess she didn’t know what to say either so she just held up a little shiny object made of glass and plastic, hardly larger than her palm and she showed me images on it, images that would materialize in the space between us. She showed me all kinds of things on that screen. Things I didn’t really care to see, to be honest.

“I’ll bet you wonder how I did that,” she said after she put her little object back in her drawer, smiling at all the pictures she had created.

“Not really,” I told her. “We have had magic in The Never for a long time.”

I’ll bet you know how she felt about that.

The day I followed Peter, tagging along as his social worker led him into the brick office building, me several paces behind, and Stegosaurus several paces behind me, the woman I talked to wasn’t there. She must have been off that day. Or maybe she finally got that other job she wanted. Or maybe she died.

What Peter’s Social Worker’s Face Looked Like:

- Like a duffel bag stuffed with towels

- Like a saturated napkin

- Like a smaller book being squished by two larger books

- Like a half-eaten sandwich

The man, the man with the face, presented Peter with the proposition of school, something never presented to me, not before Neverland and certainly not when I had met with my own social worker weeks earlier. But that’s what the man with the face was pushing. Peter wasn’t paying attention though. He was slowly walking around the office, letting his gaze guide him to the corners and tiny pockets of the office that most compelled him. Like a cold hand seeking heat under a blanket, Peter sought out the strange and the colorful in the man’s office.

“But I can’t read or write,” declared Peter, gladly.

“I don’t think they care anymore,” said the man as he wrote things down on the form in front of him as he talked with Peter.

“Capital!” cried Peter, happily.

“What are you eleven? Twelve?” he asked Peter. Peter just shrugged.

While the man poured all his attention into his work, Peter stared at the top of the man’s head. His hair looked like a cake, overcooked, but beautiful. The man stuck out his tongue as if writing about the boy was performing a difficult task.

“You need to be in school,” declared the social worker man, directly contradicting what the woman who spoke with me had said.

“According to your date of birth,” my social worker had said, “you are too old to be in school. And if you want a driver’s license you’ll have to take the driving test. Not just the written.”

I realize now that I should not have told her when I was born. But, she asked me my date of birth and by the way she said it, I could tell she didn’t think I would know. Maybe that was why I told her, just so she would be surprised that I knew. But she shouldn’t have been surprised, if you ask me. What kid doesn’t know his own birthday?

When I talked to her, I tried to tell her the truth about what I wanted and what I planned to do since going back to Neverland was out of the question. She didn’t want to hear what I had to say about things, though.

“Well, do you have perfect vision?” she asked. “Because a pilot needs to have perfect, or better than perfect vision, so if you want to be a pilot, that is the first thing you need. Did you know that?”

I squinted at her and took note of tiny details on her face, the dark ridge along her forehead, the way her hair was tugged tight like a hay bale on her head, the mole on her neck. I told her, “I can see you, can’t I?”

That made her write something down. Sure enough.

She asked me my name so I told her, but she didn’t like that either.

“Not your nickname,” she said. “Your real name.”

“That is my real name,” I told her. “People really say it and I, for real, say back: What’s up? Changing it now would just confuse things.”

“All the other boys we rescued chose real names.”

“They already had real names.”

“And you are telling me that you think ‘Tootles’ and ‘Slightly’ are real names? Do you think a person can just put a name like ‘Jangles’ on a job application?”

I didn’t know what to say to that because I did think they were real names. As real as hers anyway. Deborah.

After I left the office I had my new name, a pair of eyeglasses, and a way to draw Social Security and welfare checks, but Stegosaurus was gone. He must have gotten bored waiting for me and wandered off, or been murdered by pirates. Or gang members. Or the government. I normally wouldn’t have cared, but after getting my name changed I thought it would have been nice to have someone call me by the name I was going by in Neverland. My real name.

What I spent my Social Security and welfare check on:

- candy

- ice cream

- a box of cars I haven’t played with yet

- comic books (though I guess they call them graphic novels now)

Peter told the social worker man, the man with the face, that he would go to school, but he left the office with no intention of doing so. I had known Peter for too long not to know when he was lying, which was often. Peter kicked over a garbage can in the hall and bumped into a water cooler, spilling the water all over the worn, brown tiles of the government building; the water crept across the floor like a runner stumbling toward a finish line.

None of the other kids waiting to see social workers seemed to notice or care. The boys stood in the hallway, the soles of their sneakers pressed against the wall, their bottom lips holding up their sour faces. The girls, already women, had their tattooed arms folded in defiance. Some were fat from nearly-free, government-backed sugar, while others were too thin to stand up straight, the methamphetamines making their bodies frail and stooped.

Following Peter through the street, it was always dusk, always cool enough to need a jacket, but not so cool that it needed to be zipped. When he was hungry, he stole food from the street vendors, or from the tables of people who ate on patios and under awnings at ethnic restaurants. They all seemed so charmed by him, they all seemed to relish being robbed.

“That boy is going to be a pilot one day. I can tell just by looking at him.”

Things Peter likes to say:

- “Capital!”

- “Don’t be so stodgy!”

- “Lads…”

- “Passing queer.”

- “It is a princely scheme.”

- “Am I not a wonder? Oh, I am a wonder.”

- “Dunderhead”

- “I will blood him severely.”

- “Stow this gab!”

- “You silly ass!!”

- “Screw your courage, man. Screw it to the sticking place!!!”

- “It’s Saturday, after all.”

That’s what he always said whenever he wanted to do something. “Should we play soccer under the moon tonight? It’s Saturday after all.” “Should we go skinny dipping in The Cove? It is Saturday after all.” “Should we? Should we? Should we? It’s Saturday…”

Things Peter Deludes Himself that he Never Does:

- Farts

- Sleeps

- Shoves

- Cries

- Freaks out after he gets water in his nose

- Bleeds

I followed Peter a little bit longer. As it continued to get dark. He walked through the streets and let his curiosity guide him. He lifted up scraps of paper and shreds of clothing, kicking empty bottles into the street to see what sounds they would make, crowing softly to find out who might be annoyed and who might be emboldened by his cry.

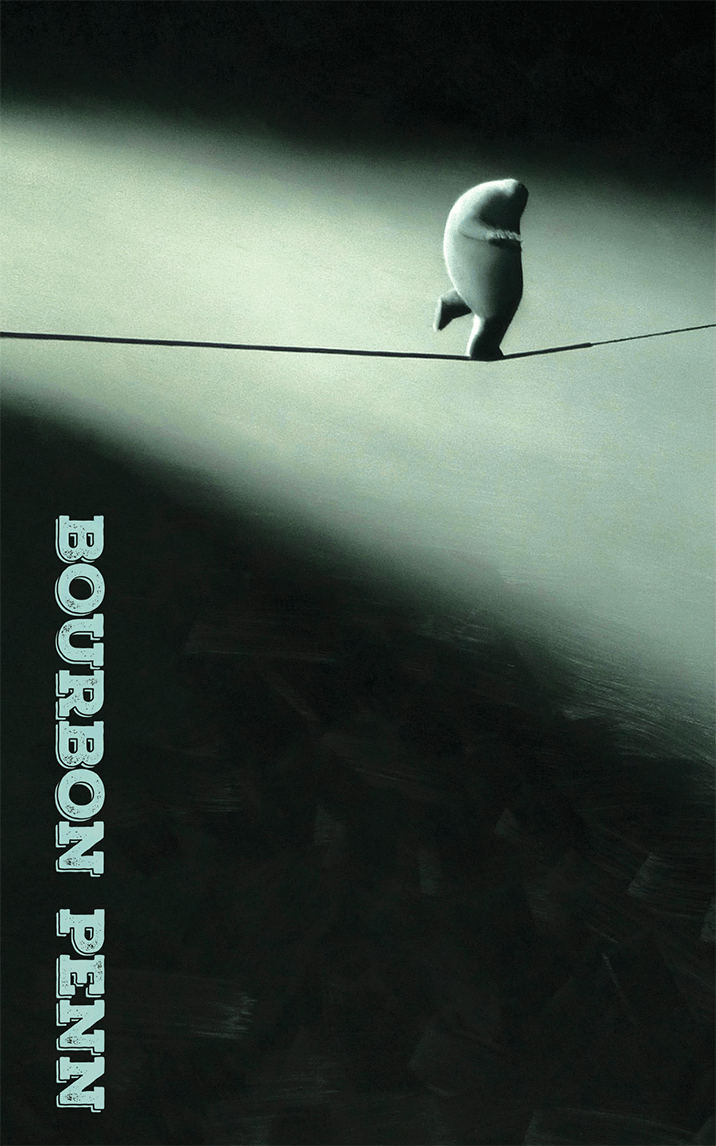

Parts of a Shadow

There are three distinct parts of a shadow; the umbra, the penumbra, and the antumbra. You’re a little surprised that I know all those big words, aren’t you? Well I do. These big Wikipedia words are most often used to describe shadows cast by heavenly bodies, but they can also be used to describe levels of darkness. About how a shadow is what is left after a light source encroaches upon an object. Or is it the object imposing on the light source that makes the shadow? It’s a real question. Sort of philosophical in nature.

The umbra is the super-dark inside part of a shadow, especially the area on the earth or moon experiencing the total phase of an eclipse. It’s the real deal. The good stuff. That hardcore, black-as-night type of shadow. It’s the stuff people make shadow puppets out of and long for on a hot day. It’s what Peter lost when he crawled into Wendy’s room that night everyone talks about constantly, as if that was the only thing Peter ever did and she was the only person he ever met. I’m not jealous. I’m just saying. I’ve met her by the way. In case you were wondering. She’s fine. A little bit of a know-it-all, but fine.

The penumbra is the sort of fuzzy outer region of the shadow. You’ve seen it. When the sun slides across the sky on some heated evening where the AC is busted and you stare at the strange, squashed diamond shapes the shutters make on the ceiling. The penumbra is that lighter shadow. The lesser one just a few steps behind the real shadow. That’s all of us. Peter’s penumbra. The dim copies surrounding him, aping him, wishing we could be closer to the center, to what is making the shadow. In Latin, I guess it means “almost shadow,” which sounds about right.

And the antumbra? Well, that’s easy. That’s the one for when you go all the way. That’s what you see when the moon is totally overtaken and encircled by the sun. Completely consumed and dwarfed. So much so that when it happens, the moon, Earth’s tiny satellite, is just a dot on the hungry sun. It happens to everyone eventually. But, think about it this way: It’s the moon that makes the sun’s corona seem so thick, like a goddamn golden ring in the sky.

I Try to Think About How we All Got Back Here to The World

I am pretty sure it started when we were having a brain fruit fight, throwing them at each other in our underground home like they were snowballs. There was brain fruit everywhere that summer. The strange, bump-afflicted fruit covered the ground, inside and out, like warts grown by the soil. They certainly weren’t good for eating. But for throwing? Capital!

We threw the green, stone-like fruits at one another, hiding behind our makeshift furniture and using our covers and sleeping bags as a fort to protect us. One of the sleeping bags was ripped to shreds during the game, of course. Peter stopped his throwing and halted the game to stare us all down, with equal measures of sorrow and mean delight in his eyes. He announced that someone would be sleeping outside that night and it wouldn’t be him. There was a long silence before I figured out what to do. I picked one of the brain fruits and threw it at Yusuf. Yusuf was sad-eyed and quiet, his cheeks sagging from his sallow, dusty face. I picked him because I knew he wouldn’t fight back.

“Let’s oust Yusuf to King Ninja Fairy and his band of evil robots,” I had said to the others. To Tootles and Stegosaurus, to Peter and Angel. I can’t tell you why I picked Yusuf, except to say that I didn’t like him. Not at all. Not that day, anyway.

“Let’s leave him locked out so they swing by and pick him up and tie him to a bale of hay and set him on fire,” I suggested because I had seen such behavior in an old movie.

“No one likes Yusuf. I don’t know why he came to Neverland to begin with,” someone said. It might have been me, or it might have been someone else. In the excitement, who could tell?

The lost boys all laughed at the thought of Yusuf alight and screaming and I thought that even if the Pirates didn’t tie him to a hay bale and burn him up, it was a thrilling, a strange, and a horrifying image nonetheless and it might be exciting to imagine it and then to bring it up again later. Peter loved being thrilled, after all. Everyone does.

Yusuf’s shoulders slumped as Angel threw a brain fruit of his own. Though it missed him, the look on Yusuf’s face registered as if it had connected. He looked around like he had done something wrong, but he wasn’t sure what.

Peter smiled in that way only Peter could. And he waited and he watched while we threw brain fruit at poor Yusuf, who could only duck as we imagined new and more horrible ways for The Pirates or the redskins, the cannibals, or the starting lineup of the 1976 Philadelphia Flyers to come and murder and torture him. Peter laughed and crowed suddenly, smoothing out the tumult like a wave smashing onto a beach.

“Or we could toss you out,” he said to me.

How Peter Smiled

- Like a snake digesting

- Like a car full of gasoline

- Like two birds fucking

- Like a monster after its meal

- Like a henchman after a kill

- Like the last of a species, ready to dive from a rock

- Like a spark, leaping loose from a frayed cord

“Wait,” I begged. “What about King Ninja Fairy?”

Fingers wrapped tight around my arms like mindless, otherworldly belts tightening around my flesh. They pressed into my skin and shoved me toward the door.

“Cast the carrion overboard,” someone said. It might have been Peter but I couldn’t turn my head so I couldn’t be sure.

Yusuf looked stunned that he had been granted a reprieve, that his fate had been reversed, that he might sleep in a warm sleeping bag, with the bodies of all his friends and compatriots surrounding him instead of being thrown out in the cold and/or lashed to a hay bale and burned to death. He put his hands on me too, taking up the mantle of the ouster, just as easily as he had accepted being the ousted.

I tried to set my feet, but I couldn’t fight the tide of all those lost boys shoving me out the door. I found myself outside in the dark, and though it was summer that day, I felt the cold of the wind bite down on my bones.

I felt small.

I knew I would be folded back into things the next day, after I’d crawled into the bushes and gotten crocuses stuck in my hair all night, after they’d found me the next day and all laughed at me for looking foolish. But I didn’t want to look foolish, I didn’t want to give Yusuf the satisfaction. And I didn’t want Peter to laugh at me. So I started walking. Out of spite, I headed North, toward where I knew there were roads and buildings and Groans. A place the lost boys had made a silent pact to avoid because we knew that only civilization could be found there. Being tossed out so unfairly filled me with a higher level of defiance and anti-authoritarianism than usual. A defiance usually reserved for The World and for Groans, but this time directed towards my fellow lost boys and at Peter.

When I got to the black top, emerging from the forest with my face smudged with dirt and dark from the night, there were cars running along the road. More cars than I remembered being on that road the last time I had made a trip to the North. Also, there happened to be a gas station that I didn’t remember. I could see giant pictures of candy and hot dogs in the window. I was pretty hungry and so I thought I might go in and raid the coins from the “take a penny / leave penny” tray and try to come up with enough money to buy some gum or a donut.

I was never able to pull off the heist though. A woman who was buying sunglasses and gasoline was able to ascertain with one look that I was a lost boy, (or “misfit” as she called me). She wore a sharp blazer and she wrinkled the skin above her forehead a lot. She could tell I was untethered from my parents and totally free and I guess she got jealous because she immediately wanted to apprehend me. Being that she was a full functioning member of The World, she couldn’t allow my freedom to continue and she started asking me questions.

When I told her about Neverland, she sent a S.W.A.T. team in there. Or, I don’t know if she sent them herself, but as a result of her meddling, the men with guns were sent into The Never. Can you even believe it, though? A S.W.A.T. team? To go and snatch up Peter? It made me kind of proud of him though, ya know? That they were so afraid of him, or at least where we were living, that they needed automatic weapons and canisters of tear gas. And some helicopters too I think, and air support, dogs, and snipers. All of it.

When they closed the door of that white van, Peter and Angel and Yusuf and Tootles were all lined up in there facing each other like the seeds of a sliced-open kiwi. It made me wonder if it was the last time I would ever see them. Or if it was the last time they would see me, sitting in the car of the woman with the blazer, listening to music, eating a taco-rito from the gas station.

I knew they wouldn’t get their hands on Stegosaurus, though. He was too slippery. And he had a weird kind of luck. He was probably shitting outside the fort when the Navy SEALs raided it, or off peeping on the mermaids in The Cove. As the woman in the blazer pulled the car out of the gas station parking lot, her headlights pointed at The World, the gravel creaking beneath the tires, I saw Stegosaurus stumble into the street, watching as the cars drove away and I wondered what would happen to him.

Finally Finding Peter

I couldn’t tell if he knew I’d been following, or if his whimsy had pulled him in too many new directions for me to follow. It was about the time I noticed Stegosaurus had caught back up with me. He hadn’t been murdered by wildcats or barbarians after all. He was trying and failing to hide in a half-full garbage can. He was probably ashamed of leaving his post in front of the social worker’s office and was now trying to make up for it. Well I’ll show him, I decided.

I snuck onto a bus through the back door and sat in one of the seats in the rear that were turned sideways. No one noticed me and I watched them twist their faces and try to make their phone calls, try to read their books.

I got off at Washington and then followed the smell of weed smoke. The scent of it wafted side to side like a meandering skunk. I knew Peter would want to follow it to find out what it was.

The Kinds of Villains You Can Find in The Never:

- Pirates

- Buccaneers (which are like pirates, but are somehow different Peter assures us)

- Soldiers

- Ninjas

- Musketeers

- Terrorists

- Martians

- The Government

- People who piss upwind of you

- Guerrillas

- Gorillas

- Apes

- Dinosaurs

- Wildcats

- Redskins

- People who don’t bury their shit when they shit

- The pantheon of Greek and Roman Gods

- Gangsters

- Gangstas

- Yer mom

- Principals

- Guys named Chad

- People who fart under the blanket and won’t lift it up to let out the smell, which is called a Dutch oven, I guess

- People who say that they are going to do something and make you feel like they are going to do it, but then don’t do it and make you feel dumb for thinking they would do it to begin with.

I found him on a stoop, clothes all wrinkled and ill-fitting, his smile cracked into a grin, his head thrown back in laughter. He was shorter than his compatriots, but commanded them nonetheless.

I was flattened and embarrassed by the sight of him, trapped by the antumbra.

“If we meet King Ninja Fairy in open fight, you must leave him to me,” Peter told one of the kids on the stoop, one they were calling Peanut. They stood there like they were balanced on top of a volcano, or were taking their places on the bridge of a space ship.

“No problem,” Peanut said.

“You got it. That mother fucker is yours,” said another. He laughed but I couldn’t tell if he was laughing because he thought the idea of Peter killing King Ninja Fairy was funny, or because he was high. The kids had the same look as the kids in the social worker’s office, mean, fragile, and coiled.

Peter puffed on the joint, the cherry on the tip glowing magnificently. He was adept, of course, though never having done it before, and the bright red of the fiery cherry was reflected in his beautiful eyes.

He laughed warmly. It enveloped us all.

They finished the joint and emerged from the stoop like a school of fish bursting from a reef, all in a group, with a noise and a color. Peter looked like he was going to pass me but I saw recognition gleam in his eyes, those eyes like broken glass at the bottom of a pool.

“Hey, Peter,” I said to him.

“Hey,” he said, stopping at the bottom of the steps. He squinted his eyes at me, trying to determine if he knew me, probably a little unsure because of those new, stupid eyeglasses the social worker had given me. I saw his eyes go steady – settle on me like a bird coming to rest on a telephone wire. Eyes so bright, like silverware polished until it made your hand ache.

“You know him?” asked Peanut.

In that moment I hated Peanut. I hated that he would expose Peter like that, embarrass him. But Peter wasn’t embarrassed, of course. He just oozed against the steps of the building, his body fitting between the cracks of the stone.

“Yeah,” said Peter, unsteady as a drunk in the morning. “Yeah, I know him.”

I smiled and he laughed. My stomach felt like it had flopped out of me and onto the sidewalk. His laugh convulsed him, grabbed ahold of him. Grabbed ahold of everyone.

Stegosaurus, for a moment, forgot he was hiding under a pizza box on the next stoop over and I could hear him laughing, too. And it felt good, like it was something that used to happen a lot, something that maybe we took for granted, but that happened no more.

And for a second I thought that it might be okay. That I could explain it all to Peter, revealing that I too had been evacuated to this city, that Stegosaurus was hiding in a pizza box, and that we shared some special secret knowledge, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I wanted to explain that it was my fault we were no longer where we loved to be, and I wanted to ask him if he knew what happened to Yusuf. I thought that maybe he might even call me by my name, my real name, slap me on the back, and forgive me. Or even punch me in the gut, just to get it over with.

But I didn’t say anything. To be absolved would require me to face his wrath, which wasn’t so terrible. Not really. But I couldn’t bear to take the blame, to be held accountable for ending the gladness we had felt in The Never, or even the gladness he was feeling with his fellows from the stoop. I resolved to return the next day, but I knew he would not be there. So ephemeral was he that he would never allow himself to form something so rigid and adult-like as a habit.

So I watched as they all slid from the bottom step of the stoop and spilled onto the sidewalk, Peter and his new fellows, the umbra of his shadow inching across the cement, the penumbras close behind, longing to be closer to the center. And I pitied them, all those fake versions of him trying futilely to keep up, because I knew that it was me who made Peter special. It was me who made him into that goddamn golden ring in the sky. It was my moon that made Peter’s sun so special. It had been me all along.

Copyright © 2018 by Matthew Thomas Meade