The Fisherman’s Wife’s Son

by Matthew Finn

The doctors arrive twenty minutes early, one elderly, one distractingly young, both in crisp white coats befitting their station, like doctors imitating the doctors on TV. I serve green tea and an expensive spread of rice crackers from Isetan, each bearing, I hope, this unspoken message: This is my life, dignified, considerate, same as yours. They are joined by a hulking, stone-faced assistant toting two black leather bags, and a silent nurse, nearly as large, inscrutable behind her white fabric surgical mask. We sit and chat awkwardly for several minutes on my living room floor, crowded around the low table of untouched crackers and rapidly cooling tea.

“Shall we begin?” the older doctor finally suggests, mercifully.

Let’s.

I allow them to strap me to the bed to calm their nerves, though I’m not convinced that they should be the nervous ones.

“So you have complete control of this thing,” the younger doctor wants to confirm as he snaps on a pair of eggshell latex gloves. “The thing submits to your will.”

“And by ‘the thing’ you mean my own body,” I say without malice. “By ‘the thing’ you mean me.” I’m not sure how else to respond. He lets the inquiry go.

When they are all four gloved and masked, the older doctor nods to his burly assistant who reaches across the bed and slides my pants down over my hips, stopping at the knees. He steps away and there’s the usual moment of stunned silence, disgust and awe. I look from one face to the next around their wide-eyed circle, then around again, like ticks on a clock. Time passes.

“The equipment,” the older doctor commands, snapping them all back into the moment.

A sheen of sweat shimmers on the nurse’s forehead as she busies herself with one of the black leather bags. She unzips and removes one instrument after another, perching them like steeled vultures along the ledge of my dresser, a grim assembly of cold silver edges and digital displays. I close my eyes as their examination begins. Their voices soon thicken to murmur, then fade completely as I retreat to my place, which is not really a place at all.

“The Genesis Memory,” my dearest Miu once labeled it, as I struggled to describe it to her, Miu’s head resting on my chest in a Dogenzaka love hotel. It always begins with a heartbeat: a thumping liquid pulse as if I am listening under water. The world is bathed in a soft red glow, like the warmth of sunlight through closed eyelids. It’s tempting to believe the heartbeat is my own, but it’s not. I know this because we always part. Some bond is severed and I’m ripped away.

So I hold on, cling desperately for as long as I can until, first softly, then sharpening, the doctors’ voices return and I’m back in the apartment, strapped to my bed. They have finished and are disinfecting their instruments. They loosen my restraints and retreat back into the living room.

The damp sheets smell of sweat and alcohol. I sit up and pat my face dry with one end of a towel as my harassed organ pat pats with the other. Then it tugs up my pants and I join the doctors in the next room.

“More tests will be performed back at the lab,” the older doctor says. “We’ll evaluate the results and figure this thing out. But you have nothing to fear. We’ll get you fixed, get you normal, living a normal life. You will be a functioning member of society.”

I thank the doctors and see them to the door.

Back in the living room I return the crackers to their box. I dump the tea down the sink, then wash the ceramic cups, placing them one by one upside down in the drainer. They are beautiful things, a gift from Miu, purchased at an artisan’s shop in Kamakura. Each is unique, hand formed, exquisitely painted with a fine ox-hair brush. I stare at the glistening wet cups for several minutes. Then, against my will, I cry.

• • •

My eyes are barely dry before another knock at the door and I know it’s my neighbor Taka. The building’s walls are thin and he hears everything. He always gives me a moment to compose myself before he arrives bearing his usual salve: two packs of Mild Sevens and a dozen jars of Cup Sake. He has a bag of wasabi chips and a bag of kaki-peanuts, the ever-present sketch pad tucked under his arm, and two pencils, as always, one behind each ear.

“Details!” he demands as he hands over the chips and sake. “I want big busty nurses and leather restraints, anal defilements for the advancement of Science.” We sit on the tatami floor and he opens his sketch pad and begins to scribble, his scarlet, acne-pitted face a mask of concentration. There’s already a page and a half of drawings imagined through the wall: the doctors cowering in the corner, me strapped to the bed raising a scalpel in one engorged tendril as a second wraps the nurse’s thigh, disappearing up her short skirt.

“I won’t let those bastards chop you, my fellow faux-functioning sub-member of society.”

I twist open two sakes and we toast nothing but their being in our hands on another starless night.

• • •

“What if they hack off your cock and you die, but your cock, as the real you, survives?”

This is Taka’s “What if?” game. It’s how he generates plots for his manga.

“What if that’s who you actually are? Your sentient core? And they dump you in an aquarium, a tourist attraction amid hostile, dead-eyed mollusks, or worse yet, smuggled away, a curiosity in a slime-green tank in a sushi shop window in the back alleys of Nihonbashi?” He sketches furiously: a bug-eyed dishwasher with a towel draped over his shoulder peers into a fish tank and pokes at cock-me with a chopstick.

“Then I won’t be able to hurt anyone else,” I say. “Problem solved.”

He stops drawing but does not look up. “You’re not the monster in this story.” He shakes another cigarette from the pack and lights it. “Remember that.”

If I’m not the monster, I’m tempted to ask, would we even be friends?

Taka hasn’t ventured more than a hundred meters from his own front door since I’ve known him. He sneaks down to the mailbox to deliver his work and crosses the street to the convenience store to stock up on essentials—sake, chips, cup ramen, cigarettes—handling his banking at the ATM, but all of this only between the hours of three and four in the morning, and only when the store is completely deserted, to be ascertained through prolonged and patient surveillance. Despite being neighbors, we never would have met if he’d had the least indication that it was possible.

It was during the summer of chaos, the electrified dawn of my romance with Miu, when even alone in my room I could not sleep with clothes on. My very skin seemed to tear at itself, restless and inflamed with need. Every night I’d pull on thin cotton shorts only to find them tossed to the floor come morning, sometimes hidden beneath a pillow or behind the nightstand. Once, when I’d had the temerity to tie my shorts with a drawstring, I woke to the pair shredded to tatters, the drawstring looped menacingly about my neck in a makeshift noose. Day and night my mind was on Miu. Night and day, my body was in riot.

At half-past three that fateful morning, after twenty minutes at his peephole waiting for a drunk to put down a magazine and vacate the convenience store, Taka opened his door and scurried down the landing. He rushed down the darkened stairwell, taking the stairs two at a time. Just four steps from the bottom he landed on me. I was deep in sleep, stripped naked and slinking down.

It was not sleepwalking, to be precise. More of a sleep-drag—a series of extensions, find a purchase then pull. It was normal in those days to wake on the floor of my apartment, under the table, or in the kitchen affixed like a magnet to the refrigerator door. But that was the first time I’d ever made it outside, and if not for Taka’s accidental intervention, there’s no telling where my night may have ended. Taka guesses Miu’s place. I posit the morgue.

Taka tumbled the final few steps to the bottom, then sprang to his feet, prepared to sprint. Desperate for the safety of his apartment, he caught a pre-flight glimpse of his obstacle, me, pantless, stunned and squirming in the damp night air. He recognized a being as freakish and malformed on the outside as he felt within. He saw in me a potential ally in this bitter world: a fellow outcast and long longed-for only friend.

And what if Taka is right? What if I had slunk all the way to Miu’s place that night? Would everything have changed?

The sake is gone, Taka’s sketch hand is cramping, and my brain is dribbling lethal thoughts like an acid-soaked sponge. I check the landing for signs of life. There is none, and Taka sneaks home.

The jars are in the sink and the ashtrays empty when there’s another knock and I wonder what Taka has forgotten. I pull open the door to a stout woman in tight black jeans and a white sweater so fuzzy she appears vague, soft and nebulous as an oncoming cloud.

“I’m very sorry,” the woman says, “but I had to talk to you alone. May I come in?”

It’s after 4 a.m. and I’m not sure if this woman is lost, deranged, or merely drunk.

“They will kill you,” she says. “And not one of them will give a damn.” She glances down at the empty street and dabs sweat from her milky forehead with a small towel and I suddenly place her. It’s the nurse from that afternoon, in a change of clothes and sans mask.

“And do you imagine I would?” I ask her.

“Let me in?”

“Give a damn, if they kill me.”

The question rattles her and I grip the doorknob, not sure what I’m waiting for.

“My name is Yumi,” she says, her painted lips quivering. “May I please come in?”

“I’m very sorry, Yumi.” I push the door closed. “It’s safer if you do not.”

• • •

Miu was the most stunning bride I had ever seen. Just twenty years old, in a pure white kimono, hair sculpted into the divine geometry of a nautilus shell, in photo after photo, eyes ablaze with the inexorable radiance of youth and hope. The groom, a sergeant, two decades her senior, wore his police dress blues and stared down the camera like it was suspect in a heinous crime. In truth, it was merely witness.

They purchased a two-bedroom condo in a Harumi tower with a view of Rainbow Bridge and the glimmering distant lights of the bay. The sergeant had the second room converted to a nursery and painted a pale blue. After the first childless year of marriage, the pressure was on. After just two, the abuse began. Miu studied the calendar and tracked her temperature and diet with a scientist’s rigor. The sergeant came home less frequently and less sober. The beatings grew steadily worse.

By twenty-six, Miu had lost eight kilos and all hope. She barely ate and rarely left the house, her wrists now ribbed with a thin ladder of self-cut scars. She ghosted the internet or stared out over the bay at the distant threads of light, occasionally taking scrupulous phone messages from her husband’s more brazen mistresses. Alone on the night of her seven-year wedding anniversary, she registered on a forum under the screenname “whatsmiu.” She’d made a plan but wanted to be certain it would work.

It would work, our virtual pharm experts agreed; the dosage would be more than enough. It would take less than twenty minutes, and she wouldn’t feel any pain.

“Godspeed Miu,” I joined in chorus. How I wish now I would have stopped writing then.

• • •

The next evening, Taka arrives at my door with a half-dozen pages devoted to my pre-dawn rendezvous with the nurse, Yumi. He’d listened through the wall. His sketchbook is beginning to read like my unauthorized biography, but he never apologizes for the intrusion. How’s he to discern, he asks, the many voices rising from within his own head from the precious few rising from without? It’s an impregnable defense.

The series begins moments after I closed the door.

Panel 1: Crosscut of Yumi and I separated by the door. Her fingertips brush the outside right where my forehead is resting within.

“A bit melodramatic,” I protest to Taka.

“Are you claiming that your forehead was not pressed mournfully to the door?” he asks.

I’m not.

Panel 2: A close-up of Yumi’s large eyes, moist with tears. “I know what happened to Miu,” she says to the closed door. “I know the truth. I know what the newspapers couldn’t print.”

Panel 3: Close-up of me, eyes squeezed shut, a man fighting back the demons of memory.

Panel 4: “Miu loved you,” Yumi says, searching for just the right words. “You gave her a reason to live. What happened after doesn’t change that.”

Panel 5: Me, shattered. I unlock the door and pull it open a crack. “Are you married?” I ask Yumi.

This last line strikes me as morbidly slapstick and I tell Taka so.

“I agree,” Taka says, “but those were your exact words.”

Yumi promised me she wasn’t married and I let her in. The following panels progressively enmesh.

The series ends with a single full-page image of our apartment building from outside. There is a man in a long coat standing in the shadows beside the convenience store. He grips a cellphone in one hand and looks up at the darkened building with its one lit window, my room, aglow from within.

“Why did you draw this man?” I ask Taka.

“Because he was there.”

• • •

The newspapers couldn’t report what they were not allowed to know. That Miu had been over an hour and a half late. That I’d rushed to greet her when my doorbell finally rang. That I was met by the sergeant with a police-issue duffel bag slung over one shoulder.

“What can I do for you, officer?” I’d asked, struggling to wrangle my voice.

He drew his service revolver and smashed the butt against my temple.

“Just be yourself,” he’d said as I writhed on the floor. “And I’ll be me.”

The sergeant gripped me by the hair and dragged me into the kitchen, the linoleum floor squealing beneath his polished black boots. He opened the cupboard under the sink and cuffed my wrists together around the drainpipe.

“We haven’t met, but I believe you know my wife.”

The duffel slammed on the countertop with a metallic clatter. I heard the zipper, the sergeant’s rummaging, then he knelt beside me with a stubby curve-backed blade.

“Do you know what this is?”

It was an Ikasaki, a fisherman’s knife specially designed for breaking down squid. I’ve no idea what subconscious murk this knowledge sprang from. “A squid knife,” I said.

The sergeant was so delighted with my answer he repeated it aloud. “Yes! A squid knife!” he said, full of mirth. “Now we’re going to see if all these fish tales are true.”

In her diary, I’d later learn, Miu had struggled for adjectives to match her enthusiasm for my anatomy. Her creative efforts bounded from “voracious” to “prehensile,” from “multi-tasking” to “empathetic.” The sergeant must have shaken his head at the twisted depths of his wife’s fantasy world.

But what to make of the mounting evidence that had driven him to find her diary in the first place? Miu was suddenly back to a healthy weight. She’d let her hair grow out and even had it styled. She was leaving home, daily. Something was wrong. She seemed happy. It was time to investigate.

The sergeant had my ankles pinned beneath his knee. My pants were down and he held the knife to the base of my cock. He’d had to swap the Ikasaki for a larger blade. We were both now mirthless.

“You haven’t cared about Miu in seven years. Why start now?”

“This will hurt,” he said. “You’ll pass out from the pain, but I have tools to staunch the bleeding and bring you around. Don’t worry, you won’t miss a thing, the party has just begun.”

“Help! Police!” a shrill voice screamed out. It wasn’t my own.

The sergeant spun, knife raised, expecting someone else in the apartment, just as Taka launched a hellbent assault against his own kitchen wall. He hurled a relentless stream of pans and dishes, kicks and profanities, even the odd limp fist dinging the drywall. The cacophony was dizzying.

Eyes shut, hands still cuffed, my anatomy rose, voracious, prehensile. It lassoed the sergeant’s wrists and neck. I squeezed.

“Are you okay?” I called out to Taka when it was over.

I could hear his hoarse sobs through the battered wall. He’d never been in a fight before. “I’m fine,” he said, “but I can kiss my security deposit goodbye.”

The sergeant was lying across my lap, wide-eyed, still. I hadn’t choked him to death. I’d crushed his larynx and severed his brainstem.

• • •

The police didn’t ask me a single question that first week; they beat me with long sticks and bowled me into walls with a high-powered hose. They’d lost one of their own, and guilty or not, someone had to pay. But none of them were willing to touch me for fear of contagion. The first doctors to study me arrived in bright orange hazmat suits.

After ten days, tempers cooled and the official interrogation began. The story didn’t make any more sense to them than it did to me.

“So, you met Miu on an internet forum where members help each other commit suicide.”

“Plan suicide.”

“Then neither of you killed yourselves. Instead, you met for coffee and fell madly in love. Didn’t this somehow violate forum rules?”

“We met for tea.”

“Were you both banned from the website for life?”

For twenty-four hours the police had been unable to contact Miu to inform her of her husband’s death. When they entered the condo they found her naked, cuffed to the top of the dining room table. She’d been sliced open from breast to pelvis. Eviscerated. A limp dead octopus placed in her mouth.

“Did you know that Miu kept a diary?”

“I did not.”

“And what about the news in the diary?” The detective paced the room with Miu’s notebook in hand. He flipped through the final pages of her life, pinning cause to effect, knowing from the beginning only how it would end. “Did Miu ever happen to mention that she was carrying your spawn?”

• • •

As days became weeks, innocence unequivocal, the interrogation flowed inevitably to negotiation. The real story was never to get out. They’d released a revised version for the media, polished and suitable for public consumption. No cock-monster vs psychopathic rogue cop, but a lovers’ quarrel ending in tragedy. It was an easy enough fiction to maintain. The police were forced to admit that I’d done them a favor in dispatching the sergeant. It would be far more complicated if he were still alive. Now they were hoping I’d tie up one final loose end. Me.

If I were awaiting trial, the detective informed me, I’d be on suicide watch. But as things stood, technically, I was a free man. They held me in a windowless concrete cell equipped with an eye hook in the ceiling, a metal stool and coil of nylon rope.

I hung a noose and paced the cell, haunted by the most painful memory of them all: sitting on a flat rock overlooking the sea. Holding Miu in my arms. Her warmth. Her smile. The scent of her hair.

“Promise me,” she’d said. “Then I will promise you.” She looked right into my eyes. She must have known on that day that she was pregnant with my child.

“I promise.” My fingers traced her scarred wrists like a man memorizing his holy text in braille. It was too easy to say, just to hear her say it back. “I promise you, my love. I will never kill myself.”

• • •

I agree to meet Yumi again in a basement coffee shop in East Shinjuku: a dozen battered tables in a plume of smoke trussing a dozen battered men as chimneys. She’s wearing her fabric mask, sunglasses, and a second skin of makeup layered thick as a crepe. She hands me an envelope of photographs from China, Russia, Belarus.

“And this is the world you want me to hold out for?” I ask her, scanning the photos. Beneath the table I contract, ill at ease.

When the focus first shifted from a radical STD super-conflagration to a standard—if abhorrently formed—Siamese-twinning, it was a welcome development for all parties involved. I was not the discarded son of a hyper-syphilitic sailor and gonorrheic-herpetic port-whore. I wouldn’t be managed by chemical cocktail. I’d be placed under the knife. It would be a risky procedure, the new doctors informed me. They couldn’t guarantee survival. The police had given up tailing me once they realized I was an easy out. I just couldn’t do it alone. Now they finally found someone to step up and catch the damned ball. I imagined them all high-fiving down at HQ. I was tempted to shake-shower in a bottle of champagne myself.

Yumi’s envelope of horrors portrays similar procedures, all of them failed. The unloved and unwanted, human beings born lacking symmetry, the abnormal, stretched out on tables, sliced and disassembled to a grisly collection of component parts. Every patient was lost and every photo was exactly the same: uniquely indescribable.

“This is your future,” Yumi tells me. “They’re not trying to help you. They’re trying to look like they tried.”

“I appreciate the effort.” I hand her back the envelope.

As she slides it into her bag, the sleeve of her blouse crawls up her plump pale wrist and I glimpse the jagged end of a scar, peeking out like the shiny purple head of a viper. She tugs her sleeve down immediately, instinctively, a cutter’s reflex I recognize from Miu.

“You are a lovely woman, Yumi.” I grasp her hand, suddenly overcome with an emotion I can’t define. “You’re beautiful, courageous, and I wish that I could know you under different circumstances, but I cannot.”

Her hand trembles in mine, and mine over hers.

“You can’t save me,” I say. “I want this. I need this.”

Yumi begins to cry, tiny swift streams trailing sediment of mascara.

“Check the forum,” she says. “Login one last time and see what it’s become. Then leave us, if it’s what you must do.”

I exit the coffee shop five minutes before Yumi. When I’d mentioned the man in the long coat outside of my apartment the night she visited, Yumi was undeterred, but we agreed to take precautions.

Out on the street I spot a black sedan halfway down the block, idling at the curb. The windows are tinted and I can’t see who’s at the wheel. I hope the car follows me. I hope they abduct me and drive to an industrial dock somewhere in Yokohama. I’ll kneel at the edge before they even ask, let them put two slugs in the back of my skull and pitch me into the bay. Get this over with. I turn and walk slowly toward the station, looking back once. The black sedan remains at the curb.

• • •

I didn’t check the forum, but apparently Taka did. He invites me over the next evening to preview his newest manga series in development. I bring the sake. He’s flush with chips.

Taka’s apartment is a mirror image of my own, but without the clean. Teetering stacks of manga climb every wall and there are at least five TVs visible from any given point, all of them on all of the time, muted and tuned to different stations. Research, he says. He doesn’t go out into the world but must draw it from here. He stares at the silent screens for hours—so this is a nightclub, this twist of slime a snake-hatchling, and over there a mob hurls bottled fire at mounted police—each image another confirmation of his one deeply held belief: Do not fucking go out there.

“Imagine there are holes in this city,” Taka says. We sit at his desk/draft board/kitchen table, a removed closet door covered with formica laid over two collapsable plastic sawhorses. He spreads his storyboard out. “Imagine descending into a subway station, mistakenly turning left instead of right, passing behind some random pillar, and just falling right through.”

His drawings portray a Boschian nightmare realm, a darkened city under the city, peopled with the lost, frightened and lonely. They hug themselves, squatting in vast shadowy tunnels, or trudge knee deep through sewage, tapping out improvised codes on a long disused network of rusting pipes. They listen for signs of life from above, desperate to be remembered, to be missed, to be sought.

“So, your hero is going to patrol the city popping manhole covers, armed with a gaff?” I ask.

“The setting is more of a metaphorical backdrop.”

“He’ll scoop them out like guppies into streams of daylight and buckets of joy?”

“This is about the people. Survival. Holding on for something.”

“I’m not sure if this is your most promising scenario.”

“Everyone on that website is talking about you and Miu.” Taka cuts to the point. “There are a lot of rumors about her death, the cover-up, about you, and most of them are true. They’ve taken a collective break from offing themselves. No more suicides. They’re hooked on your story and sticking around to see where it goes.”

“A statistical anomaly certain to confound social psychologists.”

“This is a writer’s biggest dream,” Taka says. “After the fame and fortune and mountains of pussy, it’s all about telling a story that can save lives. This is real.”

I stare blankly at a random TV screen. A string of policemen duck under a ribbon of yellow tape. There’s a voluminous chalk-figure sketched on a patch of bare pavement beside a weedy vacant lot.

I start to tell Taka the series might have a short run. My surgery is scheduled in three days’ time. I open my mouth and he silences me with a raised palm. A few seconds later, I hear it too. Footsteps on the landing. A whisper, scraping, the creak of a hinge, my apartment door being forced open. We hear several people move stealthily through my kitchen and living room, then pause at my bedroom door. It slides open. “Shit,” a voice says, sounding so close and clear it could be my own. “He’s not here.”

They move around the room for a few minutes, then the whole soundscape repeats in reverse. Taka pads silently to his front door and studies their departure through his peephole.

“Four men with guns. Look like gangsters with sensible shoes. Must be cops.” He waves me over to see a lone car parked beside the convenience store. “One stayed behind to wait for you.”

“I don’t get it,” I say.

“Well, you might want to crash here until you do,” Taka says. “But I’m locking my bedroom door.”

• • •

I wake hugging my knees on Taka’s mini sofa, the walls flickering with televised light like a plugged-in Plato’s cave.

“Have you ever had a chick and her mother on your noodles at the same time?” Taka asks from the kitchen.

“Of course not.”

He breaks a raw egg into a styrofoam bowl of chicken ramen and brings it to me. “Then you’re in for a real treat.”

I eat and watch a familiar scene on TV. The same line of cops ducking under the same yellow police tape, the same chalk outline on the ground. It appears on another channel as well, and another, drawing the great collective consciousness to a point: News being made.

They flash two photographs on the screen, first a man, then a woman, and my stomach turns.

“Volume, Taka, volume!”

He grabs a remote and points it three ways before it takes.

The chalk outline, the murdered man, was the doctors’ burly assistant, the muscle who’d strapped me down and lowered my pants. He was found last night, strangled to death. The woman, his coworker, is reported missing. The photo of Yumi is the same from her badge, sad-eyed and self-conscious in her nurse’s uniform. The police have a suspect in the case. They show a photo of the suspect. The suspect is me.

“But I’ve done everything they’ve asked! Why kill the assistant? Why Yumi? Why frame me?”

“It would take a beast to strangle that man.”

“I’m turning myself in.”

“No, you aren’t,” Taka says. “Unless you miss the sticks and fire-hosing, we’re getting you out of here. I have a plan.” Then he promptly sits down and begins drawing manga.

• • •

Taka’s plan is to out-surveil the surveillance. He spends the next four hours with his eye to the peephole. I set up on the sofa with five remote controls, casting for any news of Yumi.

“Ready, ready, ready, wait, wait, wait.” Taka runs an endless stream of disconnected commentary, never explaining just what I should be ready or waiting for. I’m not ready for any of this—for Yumi’s body fished from the bay, or another billowy chalk outline—but I wait, still.

“Ready, wait … Go!” Taka says. And when I look up, he is gone.

His door slams and I hear my keys rattle, my door open, my door close, before I’m even on my feet. Taka is in my apartment and out of breath. “Man the peephole,” he commands through the wall. “Look sharp. You’ll know when it’s time.”

“Time for what?”

Taka crosses to my bedroom. A drawer slides open, then shut. He crosses back to the front door and I can feel his presence beside me on the other side of the wall. I hear him swallow. The acoustic quality startles me. “You can hear everything from here,” I say. I’d never heard Taka this clearly from my side of the wall.

Outside, dawn is breaking. The cop emerges from the convenience store with a can of coffee, cigarettes and a curry roll. He goes back to the car, climbs in, lowers a window and lights a smoke.

“It looks like you’re going to be trapped there for a while,” I tell Taka.

“I hear every breath you take,” Taka says. “Every pathetic, self-loathing sigh. I hear your heart beat, your brain tick, and I know that you masturbate with two hands, that you cry in your sleep, that you dream of death, and that these dreams bring you peace. And death will come for you someday, my friend. I promise that. But for now, you’re going to have to wait for it like the rest of us.” Then Taka opens the door and steps out onto the landing. He’s wearing a sweatshirt from my drawer with the hood pulled up, a pair of sunglasses concealing his eyes.

The cop is nearly as shocked as I am. He scrambles for the radio, spilling his coffee across the console.

Taka is down the stairs and to the sidewalk in a flash. He sprints around the corner and out of sight before the cop is even out of his car. When the cop is around the corner, too, I step out onto the landing, go down the stairs, turn left instead of right, and disappear.

• • •

A block. A dozen blocks. Nothing changes.

The farther I get, the more lost, the more familiar the city becomes, until soon there is no curb or bench or alley I do not know. I stop at a staircase leading into a subway station I’m sure I’ve been to before, though I can’t recall when or why. Then I place it: It’s all from Taka’s art, his sketches and manga. For a man who’s spent his entire adult life in a room watching television, he’s rendered this world with prophetic accuracy, and I’m no longer sure if the city I’m traveling has inspired his work, or if this is his work, sprung from the page and projected out onto the bare white walls of reality.

I rush down the staircase and trip, tumbling, spiraling, until I finally come to rest in a dark tunnel tide-marked in epochs of human waste. A malefic creek trickles along the floor and I know before I even look that a network of rusting pipes will twine overhead. I’ve reached the labyrinth: Taka’s city under the city. My life has become the manga of my life.

I ran from the apartment because Taka had willed it, but I can never outrun this simple truth: If I’d died in jail, Yumi would be unharmed. If I’d lived differently, maybe Miu would, too.

I have crossed the zero border and entered an empty box. From here, I’ll plot the end, and Taka will have no choice but to draw it as it is.

From a length of cord salvaged from the muck, a noose is fastened to the pipes overhead. This, Taka, is the final climb. But how could a single panel ever hope to depict the crush of guilt and great shrieking panic inside?

“My Miu, my Yumi, I am so sorry,” the caption will read.

I release my grip on the pipe and swing into the void. Even as I choke them out, the words fall desperately short.

• • •

“Words fall short,” the young widow says, “but sometimes they are all we’ve got.” She sits cross-legged on the sofa in black jeans and a black turtleneck sweater, Taka’s manga, my story, open on her lap. On the page there is an image of me in silhouette, hanging by the neck, unconscious.

“We read your words and we can understand,” she says, “because we feel them. Because the pain they bear is also our own.”

On the table there’s a photo of her with her husband on their honeymoon in Izu. She leans into his chest. His arms wrap her shoulders. He was diagnosed with acute leukemia six months later, and dead seven months after that. He was twenty-four years old.

Ten days after her husband’s funeral, after the flowers had wilted and the food-bringers and company-keepers had gone, she chased a dozen sleeping pills with half-a-bottle of shochu—anything to be with him again.

She turns the page and in the following panels we see a tendril stretch up and wrap the pipe, supporting my weight as another works the cord free. I woke on the ground, hours later, with a pounding head, caked in muck. The widow was gone twice as long. She’d woken alone, her stomach emptied on the bedroom floor. “The body saves the day,” she says.

We drink green tea and talk and laugh until it’s time to leave. Before we head to the police station, she wraps a scarf around my neck to hide the cord burns, though they’re nearly gone. She places her hands on my face and kisses me softly. “We’re not alone,” she says as we walk out the door.

• • •

We’re not alone. I’d stay with a truck driver, a cellist, a college drop-out, a retiree. From ten thousand forum members came ten thousand invitations, each offering a spare futon or sofa, space on the floor or space in bed. There were ten thousand stories, ten thousand listeners, and ten thousand activists, an army of us come together and committed to a single cause. Taka drew the plan. The plan would start with one.

A woman in black jeans and a black turtleneck sweater, the young widow, walks into the Shinjuku Police station just before noon.

“Yumi, the missing nurse, we know where she is,” the widow says to the officer manning the reception desk.

He considers the proper combination of forms to offer. “Where?” he asks as he hands her two.

“Downstairs. In a cell.” Then she hands him a manga: Tentacle Boy, Volume I. “Read this,” she tells him. “Just so you know what we know.”

The officer opens the manga to a bookmarked page. In the first sequence he sees a woman in black jeans and a black sweater walk into a police station claiming to know where Yumi is. “Downstairs. In a cell,” the caption reads. Then she hands him a manga and leaves the station. On the street outside a crowd has gathered.

The officer looks up from the manga just in time to see the woman walk out the door and disappear into the gathering crowd. He lifts the receiver of the desk phone to call his commander. “Something’s happening here,” he says.

• • •

“What if this is real?” On the page, Taka is acne-free. He’s standing beside a river and points straight out of the panel, straight at the reader. In manga form he appears to have packed on ten kilos of solid muscle.

“What if all those people you see outside are real?” the next caption reads. “What if their pain, their anger, is real? Then wouldn’t the fear that you’re feeling in your gut right now, as you read this, be 100% real? What would you do then? How would you proceed?”

The manga picks up Yumi’s story outside the coffee shop where we’d met in East Shinjuku. We see her walking north up the street, the black sedan creeping behind. The car lurches ahead and cuts her off at the corner. A window slides down.

“Get in,” the doctors’ burly assistant says. Yumi does. He’s always more dangerous when she says no.

Taka would illustrate the whole sordid history, from their first date, through the first signs of his instability and Yumi’s rising fear, to her leaving him, or attempting to leave him, walking home from one nightmarish encounter bloodied and in tears.

He chronicles the stalking and threats that would lead to Yumi’s first trip to the police, where she filled out a form. Then the attack that followed, his knife at her throat in the back seat of his car, and her second trip to the police where she’d fill out the same form. On her third visit, an officer suggested relationship counseling. On her fourth, she was led to a small private waiting room where she sat alone for three hours. Then a clerk brought her the familiar form.

Taka ends the sequence with Yumi’s final trip to the police, weeks later, driving the dead assistant’s black sedan. She’d gone home first, showered, slept, then shared her story with a few thousand trusted online friends before turning herself in: how she’d been abducted in Shinjuku and driven to a vacant lot in Yokohama. How she was forced into the back seat and stripped. And how, her tormentor lost in passion, she worked her torn blouse around his neck, slid behind, and squeezed. The assistant was strong. Yumi was stronger.

“We don’t know exactly what you’re thinking,” Muscle-Taka admits from the following page, stalking the riverside, “but we do know how you think. You’ve made mistakes and now you want them gone, two birds, one dirty stone.”

The next panel is a close-up of Taka’s bloodshot eyes, fierce, enraged. “But we aren’t going anywhere,” the caption reads. “We in the margins are more than you think. We can lead and not follow. Take another look at the freaks outside. We are real, and unlike you, we have nothing to lose. Now turn the page to see exactly how you’ll proceed…”

• • •

This could be any river. This is the river Taka drew.

I step out of my shoes and wade out until the water reaches my waist. It’s a warm day, the sun high overhead, and small fish gather in my shade, pointing like thin silver darts upstream.

“That water can’t be clean,” Taka says from shore. He and Yumi sit in canvas chairs beside the tent. He’s still not happy outdoors, but with Yumi by his side he can almost feign normal. “I have considered environmental factors of course: mercury, cesium-137, atomic even,” he says. “Perhaps his father was a fisherman’s brat dragged out on the Lucky Dragon #5, trawling the Bikini Atoll. He’s freaky enough, but doesn’t glow.”

“I can hear you,” I call from the water.

“But of course that tale has already been told,” Taka says.

Taka is determined to write my origin story for Volume II, and has spent the past few weeks sketching possibilities.

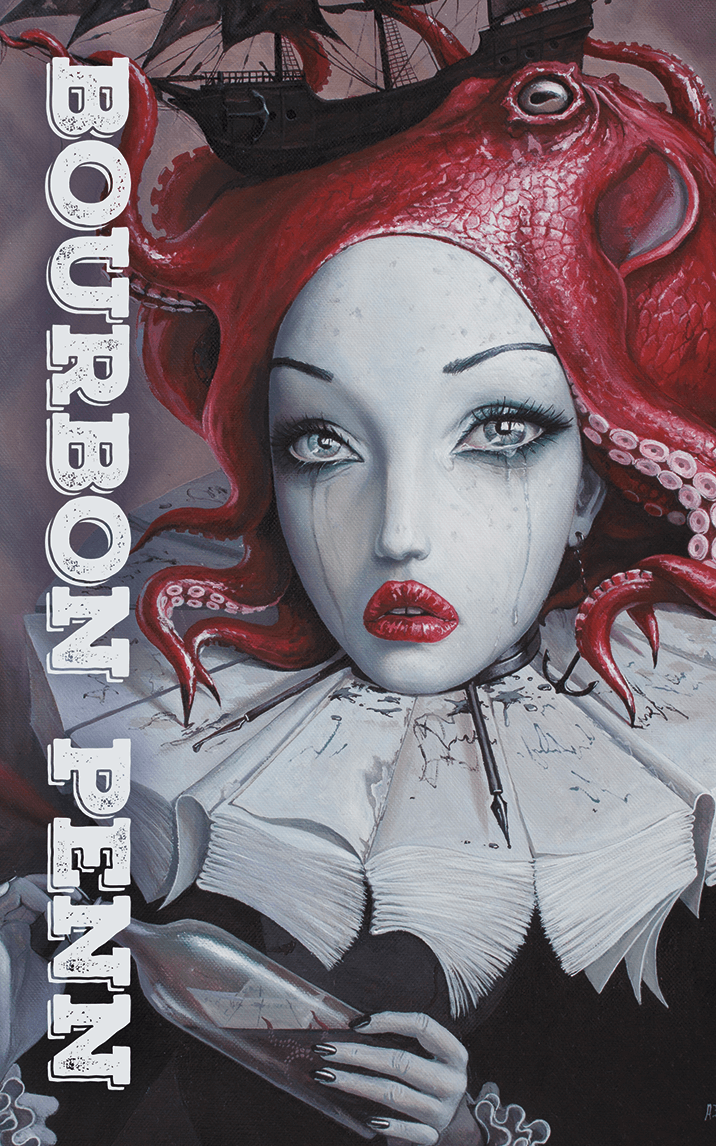

“This print is entitled ‘The Fisherman’s Wife,’” he tells Yumi, showing her a reproduction of the 1814 woodblock print from the great ukiyo-e artist, Hokusai. In it, a woman lies naked on the sea floor as she’s pleasured by a pair of octopuses. “Have you ever posed nude?” Taka asks Yumi. I wait for the sound of a slap, but hear only Yumi’s delightful laughter.

The fish drift in close to my legs and do not struggle when tentacles wrap their slick charged bodies and pass them gently into my hands. I lift them from the water one by one for a flash tour of this world. “Look,” I tell them. “There is the shore, there is the horizon, there is the city, and there the sky.” Then I show them Yumi and Taka. “And those are my friends,” I say. “I wouldn’t be here without them. Or without the love of Miu.”

The fish gawk and gape, tube-lipped, only half-believing, I’m sure, this dream world, this other side. But it’s all true, and we’re all here in it.

“Tentacle Boy, Volume II: The Fisherman’s Wife’s Son,” I hear Taka announce from shore.

I can feel him watching me, sketching my every move. I feel the sweep of his wrist and hand, his pulse racing down through the pencil, informing each line.

“Remember this,” I say as I lower the fish back into the world they know. “This is real,” I tell them as they fin slowly from my hand, into the current and away.

Copyright © 2024 by Matthew Finn