The Langsammachen Pitch

by Martin Zeigler

The attendance at Meagers Field usually matches our win-loss record, so on most game days, you'll see the ballpark less than half full. Or, if you're a pessimist, more than half empty.

But yesterday was different. Yesterday we had Horst Langsammachen, Professor of Physics at the University of Goettingen.

I tore more tickets yesterday than I ever have. More, even, than three years ago, during that brief moment of glory when the Gazelles were inching up to third place. Yes, even more than when Meagers field was chosen to hold the county's annual Car, Boat, Bike, Dune Buggy, Snowmobile, Jet Ski, 'n' Truck Show. (You'd think with all those vehicles, they could have found room for the entire "and.")

The sports lead in last week's Sentinel certainly helped. "If you must witness one miracle this year," it proclaimed, "then see the unbeatable, unbattable, unbelievable pitch of this Einstein of the Diamond, this Newton of the Hill, this Euclid of the shortest distance between the mound and home plate."

Nowhere did the article describe how the professor's pitch actually worked, but that only deepened the mystery, and nothing draws a crowd like a good mystery. Fans leaned into my ticket window and gushed forth all sorts of theories and conjectures about the secret pitch. "I hear it's a special curve ball." "I study physics on the side, and I think it follows Hortnord's equation." "Word on the street is that it can get up to three-hundred fifty miles per."

Fans having no idea what the pitch could be simply asked me outright, "Come on, Ricky, your old man must have told you something. How about a hint?"

To each of my inquisitors, all I could say in reply was, "If I knew, I'd tell you. Here's your ticket stub and your Horst Langsammachen poster."

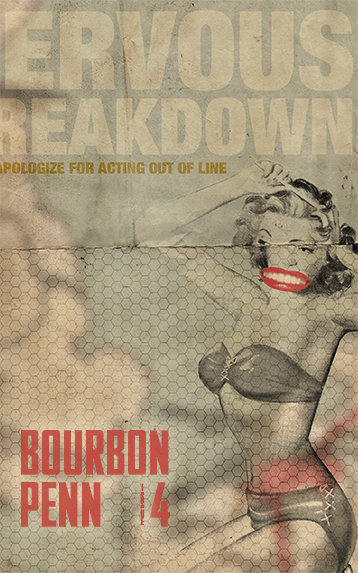

The ten-by-twenty shows the lanky hurler at the ready, his home whites shining like a hundred-watt bulb against the charcoal backdrop. His face, craggy and squinty-eyed, juts forward at you, the ill-fated batter, as he arms his mitt for the final strike.

Shortly after these posters ran out, the stadium sold out. We packed the field to the nosebleed. Even higher, since I'd squeezed in twenty or thirty extra people in violation of the fire code. And why not? We were all about to witness a miracle, and I was more frightened of that than of any fire.

• • •

You see, a month or so ago, a terrifying change had come over team and park owner Howie Meagers: he'd started to see the business side of things. After our third straight loss against the Wildebeests, Howie called my dad up to his office and said, "Tobey, it would be downright unfair of me to expect you to pull off anything resembling a championship. But you need to do something in the next — what do we have — a couple dozen home games left? In one of those games, I expect you to knock my socks off. If you don't, well—"

"Then your son Timmy gets promoted to Skipper Timmy."

"Now, Tobe. I just need a sign, that's all. The good faith of our few remaining loyal fans won't last forever. They'll be looking for a sign too, if they aren't already."

Dad bitched, but he understood. He then came home and bitched to us. "How am I supposed to pull this off? I can't make anyone hit better, field better, or throw better. I've tried the carrot. I've tried the stick. Maybe Howie's right. I don't deserve to be kept around."

And we understood. That's the great thing about our family: the three of us mull things over together. Eventually, we each get our turn at the Great Idea, and that night, over dinner, it was Mom's turn at bat.

"I think I know someone who might be of help," she said.

Mom, being German, has a whole hay wagon full of obscure relatives back in the Old Country. Although her family tree is a mystery to Dad and me, she stays in touch with almost every branch. From one such sprig — a cousin on her grandmother's uncle-in-law's side, or something close — Mom had been receiving a steady stream of clippings concerning yet another branch, a young but somewhat solitary physics professor.

Families love to keep tabs on relatives who actually accomplish something, and the latest rumor, according to Mom, was that this Professor Horst Langsammachen had devised an astonishing way to throw small, spherical objects. Or balls, as they're called outside academia.

After supper, Dad and I, with Mom's help, pored over her clippings. There weren't any articles yet on that special throw, but one amazing news item did catch our attention: how Professor Langsammachen, the leading expert in quantum mechanics at the University of Goettingen, could get subatomic particles to appear in two places at once.

This was enough for Dad. He had the same vision I did — of the ball starting with the pitcher and ending with the catcher, without enduring the voyage in between. Next morning, he marched into Howie's office and announced, "I've found a pitcher. He's invincible."

As Dad recalls it, Howie just sat at his desk and looked at him straight faced. "Invincible."

"Knock-your-socks-off invincible," Dad emphasized. "Which is why I can't reveal anything more until game time."

"We wouldn't want that."

"I'll need money for his airfare, hotel, and expenses."

"I see. Anything else?"

"Since you own the paper, a write-up in The Sentinel a week before game day. Mention physicist. Mention secret pitch. Don't mention subatomic particles."

"That last part might be a challenge," Howie drawled, "especially on the sports page. But we'll see. Is that it?"

"Posters. For game day. They're sure to be collectors' items. I brought the guy's photo with me from stuff my wife has. I figure the Meagers Field publicity boys can enlarge it to poster size, spruce it up, maybe add a uniform and a mitt."

"He doesn't have his own mitt?"

"I'm sure he does," Dad guessed.

"Okay," Howie sighed. "What else?"

Dad was so pumped, he started in on another Great Idea — as I said, our family always gets them — when Howie held up his hands to cut it short. "Tobe, you keep mentioning game day. Exactly what game were you thinking to knock my socks off?"

"Opener against Zotown."

"Against the Zebras?" Howie said. "Boy, you play for keeps, don't you?"

"Only way to play it."

Maybe it was Dad's go-out-in-a-blaze-of-glory gumption that sold Howie, but he ended up green-lighting the mystery arm sight unseen — with the understated caveat that "this better be really, really something."

Now all Dad had to do was attend to a few small details — like making sure (1) the professor was willing and able to come over here, and (2) that the professor's pitch was really, really something.

• • •

Right away, when Dad got back home, he had Mom telephone Horst. Dad and I don't sprecken sie German, so we had no idea how the conversation was going until Mom uttered a few key phrases in English which boosted our confidence — phrases like, "Yes, Horst, we'll meet you at the airport," and, "The speed of light? Why, Horst, that's very fast."

After Mom hung up, Dad and I swooped in on her like simultaneous particles. "So when can he get here?"

Mom seemed reluctant to say. "Oh, not for another two weeks. He's writing a scientific paper on that throw of his."

"Hot damn!" Dad slammed his fist into his palm. "Who else in the history of baseball not only has a lightning pitch but is writing a scientific paper on it to boot? Talk about your signs."

Unfortunately, two weeks later, the only sign Dad talked about was the one he couldn't find: Horst at the airport.

"Are you sure he agreed to this?" He asked Mom. "He does know game day is closing in, doesn't he?"

"Oh, absolutely," Mom said. Then she called Horst to make sure. Yes, she confirmed, he would be flying in the day after next.

But after another week flew by and still no Horst, I began to suspect that Herr Langsammachen had secretly parachuted into allied territory under cover of darkness and was revealing his top-secret throw to Dad at some abandoned Army warehouse in New Mexico.

The truth wasn't so romantic. What happened was that Horst missed every one of the flights we had arranged, because he was too slow getting to the airport, too slow finding his ticket, and too slow getting through security. It was only because a flight attendant was even slower closing the door that Horst finally made it aboard a red-eye.

Mom tried to explain all the delays. "Well, his last name in German does mean to take it slow."

"But Mom," I said, "since when does someone live by his last name? Does Pete Rose smell like a rose? Did Mickey Mantle play fire place?"

Okay, that second example was stretching it, but Mom shrugged it off anyway. "I'm just saying what his name means," she said.

When, at long last, we met Horst face-to-face, I realized right off what a great job the Meagers photo department had done on his poster. In real life, he didn't look intimidating in the least. With his hair slicked back flat on his head and his round wire-rims perched low on his nose, he looked frail and studious, like the guy back in P.E. who was always picked last. Any dust on his hands would likely have come from a blackboard, not a rosin bag, and he surely had had more dealings in life with the Big Bang than with big bruises.

The only thing strong about him, it seemed, was his accent, which I won't even attempt to duplicate — except this once. When we asked him how his flight went, he said, "Zuh airplane gose ferry high und ferry, ferry fast."

"That it does," we agreed.

It was late, so we drove Horst to his hotel and suggested he get a good night's sleep. On the way home, Mom, Dad, and I remained frightfully silent.

That was the day before yesterday — the night before the Big Game.

• • •

Having sold out the ballpark and then some, we ticket-takers could sit back and watch the whole game starting from the "Oh, say can you see." I had a front row seat and an excellent view of Dad pacing in front of the dugout. His cap, tilted to one side, meant he'd been scratching his head worrying.

"What is it, Dad?" I asked, when he approached within earshot.

"No Horst. Where's Horst?"

"Wasn't Mom supposed to bring him here?"

"Where in the heck is Horst? How can I knock Howie's socks off without Horst?"

"Have you seen him pitch yet?" I asked.

My Dad gave me one of his do-we-have-the-same-genes look. "Ricky, when have I had the time?"

"Well, then, how do you know you'll knock Howie's socks off, even with Horst?"

I knew my wisecrack had gone too far when I caught Dad's revised look, which had less to do with genes and more to do with murder. I started to apologize, when, to the lively cheer from the stands, the Gazelles poured out of the dugout, with Horst bringing up the rear.

Dad called out to him, "Horst, where have you been? Are you ready?"

Horst looked over and spotted us. "Good morning. Or is it evening? I think I have a tiny jet lag."

"Well, get out there and throw some practice pitches."

"There is no need for that."

Miracle Man or not, this was not the thing to say to the skipper. "What the hell's that mean?" Dad growled. "You practice in your hotel room, or what?"

"Ja, that is exactly what I did."

And with a tip of his hat, which, like the rest of his uniform, looked a trifle large — the result of being issued spare duds on such short notice — the professor trotted out to third base. From there, he was directed by the cornerman to the clump of dirt at the center of the diamond.

• • •

The infamous Zotown Zebras are the most irritable, impatient, humorless team in the league. At the plate, before the pitch, their batters refuse to take practice swipes or to bless themselves or to fiddle with their batting gloves; they just want to see the pitch. And when their infield gets a guy out, you'll see none of that time-honored ritual of around the horn. No, that just uses up valuable seconds. Probably the reason the Zebras are in first place is they didn't want to waste all that time being in second or third.

Their lead batter, a miserable guy by the name of Doug Mudman, stepped up to the plate to begin the game. Being a Zebra, he didn't go into a song and dance but just hunkered down for the first Langsammachen pitch.

Everyone in the stands was probably asking the same thing Mudman was: what's this guy got? We'd hoped for a sneak peek at the professor's miracle, something akin to watching Jesus take that first step on the Galilee, but Horst had revealed nothing. He hadn't delivered a single practice pitch. He'd just stood on the mound like a gangly, lost boy.

Even as Langsammachen threw his first pitch, it took a minute for us to realize he was doing anything at all. He didn't lean forward to take in Carlson's sign. He didn't go into a windup. Instead, he stood tall and still as a beanstalk, holding the ball up between his eyes. Then, with a flick of his wrist, he gave the ball a little fling as if throwing a dart down at Gooley's Bar on a Saturday night.

The ball inched forward a bit then seemed to float in midair.

A murmur passed through the stands, followed by a smattering of giggles, as if the spectators were laughing at a joke they didn't quite get. And to my right, I heard something that I doubt anyone had ever heard at a ballpark before: "Look! I think his pitch is moving!"

To me, the ball looked perfectly still, but I was practically looking at it head-on. A glance over at the radar display, though, showed that I was mistaken. The ball was indeed moving. At the blinding speed of .014 miles an hour.

Doug Mudman was not happy. He never is, but right now he was particularly unsettled. Finally, he turned back to the home plate ump. "Is this some kind of joke?"

When the ump didn't answer, Mudman glared down at Carlson. "He's your teammate. How long am I supposed to effing stand here?"

I felt it wasn't my place to inform Mr. Mudman that I had worked it out. The ball was moving at about fifteen inches per minute, which meant he had roughly a forty-eight minute wait.

Getting no reply from our catcher, Mudman screamed at the pitcher, "Okay, Longshoreman, you've had your fun! Now throw the damn horsehide the way you're supposed to!"

When Horst put a hand to his ear to show that he hadn't quite caught that, Mudman, his batting arm convulsing from the urge to swing, now yelled something that not even we seasoned fans could make sense of.

At that point, Professor Horst Langsammachen stepped off the mound, sauntered onto the grass, casually overtook the ball that was still making its way to the plate, and stopped just shy of the three boys at home. "I don't hear so good these days," he explained, "probably from all the noisy lab equipment back in my hometown of Goettingen."

"What are you doing here?" Mudman said. "Get back out there."

"He's right," the ump said. "You want to clear the benches on the very first pitch of your career?"

The lanky pitcher looked puzzled. "What means that — clear the benches?"

"It means get your ass back on the mound," Mudman clarified.

"It is very lonely there on the mound. Not unlike my lab in Goettingen. The three of you here, we are friends, ja? Maybe I buy you each a beer from the concession stand. Is that what you call it — concession stand? Although the beer here is not so good like German beer. But matters not. I bring back a bottle for each of you. Then the three of us, we all have a nice chat until the ball arrives, ja?"

"Nein," the ump said, pointing to the mound.

Horst's head shot back as if slapped, then just as quickly bowed in acceptance. "We chat some other time."

As Horst bypassed the slowly advancing ball on his return to the mound, Mudman called out behind him, "Chat this, Longshoreman!" Then Mudman took his bat and cut an angry swath through the air.

"That there's a strike," the ump said matter-of-factly.

"Strike?" Mudman fumed. "What do you mean, strike?"

"You swung."

"Why would I swing? Can't you see the ball, ump? It's still halfway back there at effing Timbuktu!"

"You mean you didn't swing?"

"Yeah, I swung. But not at the ball!"

"That happens," the ump said. "And when it does, it's called a strike."

"Oh for God's sake."

"Now, if you don't mind...." The ump pulled off his face mask and shouted right past Mudman's ear. "Hey, Mr. Langsammachen! While you're there, son, how about fetching that ball and pitching the next offer?"

"I have a better idea," Mudman said, glaring up close at the ump's still bared face. "Why don't you get your seeing-eye dog to fetch it for him?"

So Mudman was out of the game.

It took two strikes for a similarly touchy Williams to get booted.

Harrison, after three quick strikes and one equally quick insult, was not just out, but out.

As for Langsammachen, he was given not only a standing O for his first ever inning in the minors — and an impressive fifty-two-minute inning at that — but also a Richter-busting cheer for his three casualties. Especially celebratory were those fans who measure the length of a ballgame in beers per inning. Longsammachen, it seemed, would forever hold a place in their stats-and-suds-loving hearts as the guy who allowed them their highest BPI.

• • •

After the bottom of the first whizzed by in normal Gazelle fashion, Dad ambled up to me with another look — this time, a "My God, what have I done?" look.

"Fans seem to like him," I said.

"Horst keeps this up, we'll win on a forfeit. Do we really want that?"

"Maybe it takes him a few innings to warm up to light speed."

Dad shook his head hopelessly. "I asked him about that just now. I said, 'Horst, when my wife spoke with you on the phone, she got all excited about the speed of light. She was talking about your pitch, wasn't she?' And Horst sort of backed away and said, 'Ach, yaaaaa. But maybe she misunderstood. What I told her was, compared to my pitch, everything seems that fast.'"

"It's the German verbs," I suggested. "That's why I took Spanish."

Dad studied me for a moment. "Ricky, call your mother. Tell her we'll be late for supper."

"I did the math. I hope whatever she's making will keep for three days."

• • •

Thanks to the Deities of the Diamond, the game didn't last that long, but it lasted long enough. Zebra after Zebra swung early and often just to get his at-bat over with. Their skipper, Marv ("Nervous Nellie") Nellison didn't take too kindly to that, but at least these players resisted making pronouncements about the ump's cataracts or the pitcher's political leanings.

At the seventh inning stretch, a devoted choir of fans up in the 300 section launched into a slow-speed rendition of Take Me Out To The Ballgame. It continued through the Gazelles' luckless swings. And by the time the Zebras deliberately brought the top of the eighth to a merciful close, the chorus had reached as far as the Cracker Jacks.

The score was still goose egg to goose egg at this point, and our half of the eighth did nothing to change that. It looked like a stalemate for sure: we were pitching too slowly to the Zebras, and the Zebras were pitching their usual speeds to us. Our only consolation was that our human U-Boat was keeping the enemy at bay with his torpid torpedoes.

Then, top of the ninth, Nervous Nellie brought out a weapon of his own — a rookie as green as center field. Chile Verde was so green, he hadn't yet picked up the team's habits. He stood in the batter's box in a state of absolute calm, as if he had all the time in that little rectangular world for the Langsammachen pitch.

You can't imagine how enthralling boredom can be until you actually experience it. We Gazellians stared at that ball as if under hypnosis. Somehow, we knew this one would go all the way, and we were intent on tracking it through its entire journey.

Forty minutes later, the ball was over the plate — the first Langsammachen pitch to have made it this far in the entire game! It was like watching a century-old record being broken — while being there for the entire century.

But then the ump turned to face the crowd. As if demonstrating a textbook case to a lecture hall, he pointed to the near-motionless baseball. It was shin-high to the rookie. Ball one.

The desperate groan that flooded through the stadium echoed, in a magnified way, the disappointment we might feel at mail-ordering a package from some distant country and, one month later, getting an empty box.

After two hours of three similar shipments, Mr. Verde was rewarded with a walk to first base.

Dad admitted to me later he would have visited the mound during this four-ball ordeal had he not been as mesmerized as the rest of us. When he finally did get out there, just after the walk, Horst was ecstatic. "You come visit me on the mound! Perhaps someday you, your son, and your lovely wife — you visit me in my hometown of Goettingen. I will show you my pitch under — how you say — laboratory conditions."

Dad nodded politely. "I can't think of anything else I'd rather do, Horst. But right now we're not in a lab. We're in a ballpark. And you have to throw strikes."

"What means that — throw strikes?"

"Baseball, Horst. Don't you understand—"

Dad didn't finish. He just shook his head and plodded back to the dugout. He didn't pull Horst. How could he? Even though Horst was probably the first pitcher in history not to know what it meant to throw strikes, he could also very well be the first in Gazelles' history to throw a no-hitter.

• • •

It was that kind of game, where anything could happen. But what happened next, we should have seen coming. This seems a strange thing to say in a game where, in the time it took the ball to reach the plate, you could drive thirty miles down the road to play chess with your Uncle Charley — but it's the truth: we simply did not see this one coming.

A minute or so after Horst nudged the ball forward for the next pitch, Chile Verde took off from first — not at breakneck speed, the normal way to steal, but at a window-shopping stroll. After stopping at second to spend a good half hour (every minute, I hear, well-spent) instructing Mike Salmon on the proper way to balance one's investment portfolio, Chile moseyed onto third to give Carl Gillette his assessment of the various artists in the Hudson River School. Then, following a few arm and leg stretches to get his joints working again after having stood still for so long, Mr. Verde bid a fond farewell to third base and continued his long but leisurely journey home.

So many things happened when he touched the plate, it's hard to remember them all. The first run of the game was scored, we all remember that; a three-base steal went into the record books; Carlson, the catcher, threw his mitt in the dirt and cursed the slowness of the game for affecting his wits. "I could've interfered with this pitch and advanced him only one," he moaned. The umpire remarked how this was the most relaxing game he had ever officiated and how sorry he was to see it near an end, Horst hung his head low, somehow understanding that what just happened was not in the team's best interest, and the choir in the 300 Section finally concluded their seventh inning stretch aria.

The only thing that did not take part in this great confluence was a certain small, spherical object.

The rest of the game — the two deliberate Zebra strikeouts and the nine desperate swings by the Gazelles — was mere formality.

Afterward, in the parking lot, Dad said to me, "Ricky, do you think when you have time, you'd be able to teach me a thing or two about selling tickets?"

Then down from Valhalla came Howie Meagers. He clapped a hand on Dad's back. "Tobe, you gave me the riot of my life. I'm barefoot, my socks flew off so fast. Or slow, depending. Seeing Nervous Nellie and his boys get steamed was worth the price of admission."

"But they won."

"So what if they won? You gave the fans a sign. And that's all I asked for."

"Well, well," Dad said, suddenly in high spirits, "with a few pointers, we can get Horst — uh — up to speed on some of the basics, like—"

Howie stopped him. "My socks are back on, Tobe. They're woolen, and they're warm. It's business as usual. Lose the Kraut."

• • •

A few hours' rest, and I was back selling tickets for today's game. The lines were shorter compared to yesterday, but the die-hards still wandered in for what was sure to be another nail-biter against the Zebras. Dad was thrilled to still be managing; he was sitting in the box seat of life. Poor Horst, though, fearing he had done something wrong, was in life's back section, stuck behind a column. It would be a week until he flew back home, and until then, it looked as if there was no consoling him.

I was trying to think of how to keep the poor guy occupied when Howie Meagers dropped by with the news. Yesterday's concessions, especially the brew, broke all sales records. He asked if I would kindly give the physics professor his sincere thanks.

I told Howie that if he really were sincere, he could do better than that.

And Howie came through.

Last I looked, the foil-wrapped peanuts and dogs were still hovering in midair, just out of reach, but the patrons didn't seem to mind. They settled in for the wait, took in the Gazelles' admirable consistency, and now and then chatted it up with the lanky new vendor.

Copyright © 2012 by Martin Zeigler