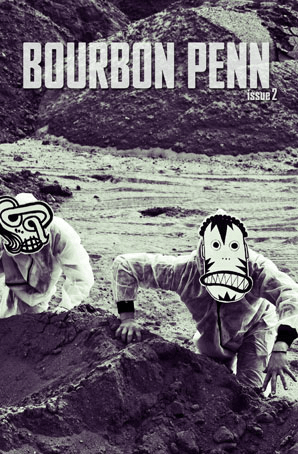

Scenes from Monster Beach

by Matthew Bey

The first attack Totsuru remembers, he was twelve and visiting the beach with his family.

Every summer they visited the beach. Essentially the same things happened every holiday, so Totsuru’s memory of that particular weekend is a collection of routine events from many different years. When he thinks of the attack (which is often), he watches a slideshow of images that are polished and worn from many recollections.

These are the things he remembers:

One: His father pitching the tent with the usual bumbling confusion.

Every summer his father would have to re-learn how the tent came together, what order to assemble the dozen poles and two dozen stakes, which loops of canvas supported what. His father would roll up the sleeves of his white shirt. On the second attempt to pitch the tent, his father would laugh, knocking himself on the head with his knuckles, exclaiming, “Baka! Baka!”

Two: His father walking in the surf.

Totsuru’s father would take off his leather shoes and black socks and roll his slacks up to his knees. It is the most he would undress during the entire vacation, and it is the closest to naked that Totsuru would ever see him.

Three: Proudly praising their tent.

The tent had twice the square footage of Totsuru’s bedroom back in Ichiyo City. The thick army-green canvas could repel all but the most torrential of rains. The roof was double-peaked like a temple and tall enough to stand in. There were zippered doors at the front and back that Totsuru’s mom rolled up to allow the passage of the cool ocean breeze.

Four: Hunting for shells and interesting flotsam.

The barrier islands stretched along the coast in gentle curves so huge that from ground level the beach looked like a dozen kilometers of ruler-straight line. Totsuru would run along the hard-packed sand of the surf until he could barely see the green spot of the family tent. Then he would return and run past, going just as far in the opposite direction. Everyone in Ichiyo City could have an acre of beach to themselves if they had wanted, the scrub-covered dunes at their back and the blue-green world-ocean stretching to the sky at their front.

Five: Squinting at the mechakaiju, hoping to see them move.

The offshore sentinels, the distance cloaking them in a uniform silhouette of gray, stood submerged to their robotic hips. They seemed to ignore the Neo-Nihon coastline they protected, their steely faces turned to the sea.

Six: Totsuru’s father drawing in the sand.

With graceful strokes of gnarled driftwood he drew the character for Yamaginto, a yokai of the hearth and the home. “It never hurts to be careful,” he would say, winking at Totsuru.

Seven: His mother sunbathing.

She wore a two-piece bathing-suit that revealed several inches of her torso including her bellybutton. In later years she will deny ever having worn anything so scandalous, or having exposed her ivory skin to the sun.

Eight: The amazing canopy of stars overhead at night.

They sat around a campfire of driftwood, roasting yakitori and marshmallows. Out at sea, the mechakaiju could be seen by their deck after deck of running lights and the sweeping beams of searchlights.

Nine: The ceaseless roar of waves.

The surf was so like the roar of traffic in its ubiquity, but so different in every other way.

Ten: The flocks of pterasaurs.

All day long they skimmed the waves with the tips of their leathery wings, gliding in a perfectly regimented line.

Eleven: A glimpse of a scaleddolphin fin.

Although he stared a long time at the ocean, he never caught a second glimpse of that famously capricious reptile. He had read stories where scaleddolphins had a city beneath the sea where rescued sailors lived in grottos, dining luxuriously off seaweed and sashimi. In retrospect, Totsuru doubts he actual saw that fin. Perhaps it was a memory born of wishful thinking and a child’s imagination.

Twelve: Finding a handfish in the flotsam.

He kept it alive in an old baked-bean can filled with saltwater. For hours he stared at it, waiting for the invertebrate to open its five tentacles, their venomous pink tips waving blindly in the can. In the middle of the handfish’s “palm”, a tiny beaked mouth opened and closed. When Totsuru poked it with a sliver of bamboo it would contract into a leech-like ball, giving him the pleasure of waiting for it to unfold yet again. Totsuru cannot remember what happened with the handfish, whether he released it back into the surf or if it was forgotten on the beach in the panic following the attack.

Thirteen: Laughing and playing in the surf.

Totsuru jumped into the air and tucked into a ball as each wave slammed into him and dunked him in froth. Then his father was there, clutching him to a drenched white shirt while his mother screamed from the shore. Totsuru could hear the thumps of distant explosions like a thunderstorm in a cloudless sky. Both he and his father stared out to sea, holding each other, watching the megasaur that waded through the sea on its hind legs. The mechakaiju sent a stream of short-range rockets into the beast, the contrails hanging in the air like ribbons. Then the two shapes merged as the megasaur charged. There were flashes of light and clouds of steam and spray, and then only the megasaur stood there. With jaws dropped, they watched as it waded to shore, only a kilometer to the south of them, stepping over the dunes like anthills. It passed over the barrier island and was out of sight even before it stepped into the intracoastal waterway on its way to the populated heartlands.

• • •

Totsuru was twenty-four when he experienced his second attack. They were already talking about the megasaurs having a twelve-year cycle, so they expected it. He was serving out the last month of his mandatory three-year military service, deployed deep in the belly of a mechakaiju. His station lay in the mechakaiju’s torso where a man would have a gall bladder, but the mechakaiju only had bare pipes, cramped passages, and the smell of many young sailors who had not seen the shore in months.

When the sirens went off, he strapped himself into the shockchair at his battlestation and folded his hands on his lap in a calming zen mudra. He breathed deliberately from his diaphragm, his eyes shifting between the fire-extinguisher and the reactor coolant valve, the only two things he would have to worry about during the fight.

He could hear shouting echoing through the steel frame of their robotic beast and the clanging of navy-issue boots on walkways. There was a rapid “fuffpt-fuffpt-fuffpt-fuffpt!” as the shoulder-mounted rocket battery expended its payload.

Totsuru’s friend Ako ran past him, mussing Totsuru’s hair with a free hand and reaching for the safety handrails even as the mechakaiju lurched in step. “Buck up, Stinky! She must be close if they’re firing off the chubbies!” Then he turned the corner, on his way to his station at the elbow servos.

“Fifteen seconds to contact!” shouted a voice down the ladder hatch, and other voices at other stations repeated the news in eager, terrified voices.

The mechakaiju lurched and shifted again, a motion that Totsuru recognized from the drills as shifting into fighting stance. Blocky boots the size of houses were settling themselves into firmer positions against the sea floor. The explosive chatter of the heavy machineguns rattled in his ears.

The megasaur would be close enough now to see the decorative details of their mechakaiju. As the beast saw the face they had crafted for their machine, a huge white mask shaped like a mouthless kitten, what did it think? Did the megasaurs think at all?

Totsuru’s thoughts turned to his family and the weekend holidays on the beach. The place they had camped lay many tens of kilometers away, but the beach that stood behind them would be the same. There would be waves and there would be dunes. The sun would beat down from a blue sky.

With all his heart he wished he were there, his toes curling in hot sand.

And with all his heart he wished he were on the command bridge, staring through the twin eye-shaped viewports at the many megagrams of furious reptile that charged toward them.

“We have contact!” came the shout from the hatch.

The mechakaiju boomed and reeled from impact, and Totsuru’s head knocked violently against the shock padding. His mudra came undone as he gripped the straps of his chair with whitened knuckles. His vision blurred, and he squinted to focus on the dancing needles of the reactor gauges. A lizardly scream pierced through the steel skin.

From all about Totsuru came excited shouts, the creak of metal, the shrieking of servos pushed to their limits, and the flashing red of alarms. The mechakaiju shook and tilted. Totsuru could smell smoke, but there was no flame in his station, so he ignored it, his eyes focused on the dancing needles.

He heard the clank of the chest bay opening. The shouting stopped (Totsuru remembers an expectant silence, although he knows that there could have been nothing of the sort at the height of the battle). The chest bay hid the X weapon, a weapon that had never fired, that they had only dry-fired in maneuvers, opening the hatches while facing out to sea, and only after they confirmed that no shipping traffic lay above the horizon that could witness the device hidden within the mechakaiju where a man would have a heart.

There came a noise like the moon splitting in two and dropping through a hole in the sky. The reactor needles redlined.

Totsuru had unbuckled his straps and lurched across his station to put his hands on the valves when the needles dropped back and the mechakaiju shifted smoothly into an upright position. Happy yells drowned out the alarms.

“She’s turned back!” shouted the voice from the hatch. “We sent her back to sea!”

Totsuru sighed, flopping into his shockchair and wiping the sweat from his face.

• • •

The third time he sees an attack, Totsuru is thirty-six and a post-doctoral researcher at Ichiyo University. They had seen this attack wave coming a long way off, but they no longer call it an attack. They call it a cyclical migration event.

They know far more about the megasaur lifecycle than they did twelve years before. Sensors attached to automatic buoys, thousands of kilometers out in the world ocean, watch the deep-water trenches for movement. A command center buried beneath Ichiyo Capitol tracks every mature megasaur as the beasts move deep beneath the surface, eating the detritus drifting down through five kilometers of water, the sinking corpses of whales, the clumps of krill bodies falling through the water like snowflakes. Every megasaur has a name and a number. There are no surprise monsters.

It takes almost a week for a megasaur to depressurize as they slowly rise to the surface. It takes another week for them to swim toward the continental landmass. The orbital satellites had tracked this one for days. The computers had long since plotted its statistically most likely point of landfall.

Totsuru stands on the precise GPS point that is most likely to see the megasaur’s foot. He looks out to the sea, waiting for the lizard to breach, expecting the great scaled head to break the surface, bony eye ridges and curving horns parting the waves like the prows of ships.

The expected landfall lies shockingly close to where Totsuru’s family used to camp. The convoy had used the same beach access road, their APCs roaring along the sand through the ghostly memories of holiday campsites. The marines had already rousted all the campers from this portion of beach, clearing out an “encounter zone” for five kilometers in either direction.

Most of the marines are too young to remember much of the last migration event. Totsuru, having personally encountered megasaurs in the two previous cycles, is respected as a veteran by these fresh young faces. Totsuru is the old salt.

The marines bustle about, setting up their own tents, stretching cabling and equipment. They wear desert camo fatigues that do double-duty here as beach camo. Several of them had expressed surprise that Totsuru, their civilian advisor and the designated scientist of the detachment, wasn’t wearing a white coat. He had explained to them that lab coats were for the lab, and bermuda swimming shorts were for the beach.

For the marines, the beach is not a holiday getaway, it is a convergence of tactical situations. It is a place to establish beachheads. It is a place where people die.

For Totsuru, the beach is no longer a holiday getaway. It is a confluence of environments. It is a place where animals and plants interact in dynamic modes, where predators and prey encounter perils evolution had never anticipated.

Out to sea the mechakaiju stand as Totsuru remembers them. A squadron of jetlifters had deposited them at their stations only an hour before, taking off from the mechakaiju base in Katsurayo only after the computers made their final projections. These mechakaiju were Mark Eight, a sleeker and more efficient model than the one Totsuru served in. When they moved, they moved like men a hundred meters tall.

When Totsuru moves back from the roar of the surf, he hears the commotion of the communications tent, the relay of information from the Ichiyo command center, to the mechakaiju, to the beach team, to the spotter planes and back again. A ripple of excitement passes through the tent, and Totsuru looks out to sea in time to see the megasaur stand up out of the water. It spreads its arms like a wrestler and throws its head back. Several seconds later, its roar lashes across the beach. They now know this roar is part of their mating ritual, the sub-audible sound waves will continue on into the interior of the heartlands, an invitation to females who are not there, who will never be allowed there again.

The mechakaiju are already on intercept, the sea foaming around their hips, their sleek arms held at shoulder height as they wade.

The megasaur can’t choose which battle robot to attack, it almost seems to cower as they converge from both sides.

Totsuru takes out his notepad. There will be video footage from a dozen sources, but he wants to write his observations before he forgets them. A series of organs across the megasaur’s snout has the job of sensing electrical fields, and another near the corner of its eyes senses infrared heat radiation. The sensory combination of these two organs makes it almost impossible for the megasaur not to lash out at these hot metal bodies that bear down on it. This also is something that they had not known twelve years ago.

Totsuru finds himself knee-deep in the surf, sand seeping into his sandals and between his toes, the pen scrawling across paper.

The lizard screams as the machines seize him.

“Prepare the tankers!” Totsuru yells. Marines scurry to do his bidding. He is their civilian advisor. He is the expert on the lizards. He is the old salt.

It takes twenty minutes for the mechakaiju to drag the beast to shore, wreaking unspeakable environmental damage to the seabed in the process. They hold the megasaur by either arm, the strength of their next-gen fusion servos overwhelming the reptile’s hormone-fueled mating lust. With jujitsu moves tailored to the megasaur skeletal structure, they force the beast down at the shoreline, pinning him with arm-bars and bent wrists. The left-side mechakaiju plants a foot between the megasaur’s horns, forcing his jaw into the sand of the beach.

Trapped and immobile, he whines through clenched jaws bristling with fangs.

Totsuru stands on the beach, cradling a needle the size of a horse’s leg in his arms, the pressure hose snaking back to the tanker trucks. When the megasaur sighs, cold air the temperature of the sea bottom blows from his nostrils and ruffles Totsuru’s white shirt and bermuda shorts.

Almost leisurely, Totsuru walks around the reptile’s snout until arriving at an eyeball twice as wide as a man’s armspan. He barks a request at the marines who carry the pressure tubing like dancers holding the train of the New Year’s kirin. A moment later, the left mechakaiju twists its foot, forcing the head to rotate until the megasaur’s eyeball is nearly touching the sand.

Standing close enough to touch the milky light-catching lens that covers the beast’s pupil, Totsuru hefts the needle to his shoulder and gently fits the tip into the tearduct. The translucent tissue of the megasaur’s cornea does not reflect Totsuru’s image no matter how hard he stares. He waves his hand, and the trucks start to pump.

It will take another hour to properly dose the megasaur with the drugs that will chemically castrate him, will erase his urge to trample and feast and search for a mate. They will allow a few of the megasaurs to spawn in carefully regulated preserves close to the coast, but most will return to the sea with their lusts thwarted. The population will decrease, but with proper management they will survive.

As he rests the needle on his shoulder, the pressure tubing humming in his ears, Totsuru looks out at the surf, gazing through the straddled legs of a mechakaiju. He sees the dorsal fin of a scaleddolphin cresting over the peak of a breaker. Shouting and pointing he draws the attention of the marines. They look just in time to catch the scaleddolphin leap from the water, its long tale curling as it somersaults.

The marines laugh and yell.

Totsuru knows it’s just a coincidence of evolution and anatomy, but the scaleddolphin looks like it is smiling.

Copyright © 2011 by Matthew Bey